In 2000—just before yoga and then meditation appeared on the cover of Time, and years before the term “green” meant much more than a color to most Americans—sociologist Paul H. Ray and his wife, psychologist Sherry Ruth Anderson’s book, The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World announced the fruition of 12 years of research: 26 percent of Americans had a starkly different set of values (caring for the environment, women’s rights, meaningful work over money) from the mainstream. The only thing keeping this bloc from exerting its muscle was a lack of awareness of and communication with itself.

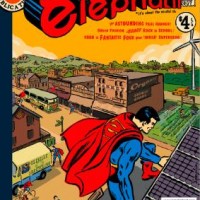

Five years later, “sustainability,” “eco” and “green” are catch phrases in America’s boardrooms, meeting halls and even in Washington, D.C. Magazines such as this one are working to bring together those Cultural Creatives’ voices—and get their message out to the other two blocs of Americans—the Traditionals (cultural conservatives, also about 20 percent of the population) and the Moderns (mainstream, secular materialists).

We sat with Ray at the end of a weekend hosted by green giant Gaiam (which sells eco goods and yoga mats in Target etc.), that brought together 100 of our hometown’s cultural movers and shakers. May it be of benefit! ~ ed.

Waylon H. Lewis, for elephant journal: We’re here on a beautiful autumn day in Boulder. I understand you’ve just been leading quite a weekend.

Paul H. Ray: Yeah, “Visioning 20/20.”

ele: Are you inspired, having come to a town well-known for having Cultural Creatives—-and inviting 100 leaders out of that community?

Ray: It’s always fun to come to Boulder—my first visit was in 1970. I come four times a year for board meetings. It’s fascinating to see how many environmental activists and green businesses are doing projects here—and yet don’t know each other. So we all got together trying to envision a sustainable society—tuned in, listened beautifully to each other, created together. I’ve done this visioning stuff all over. In Vancouver, Seattle, Portland and Montrose.

ele: And visioning is where you take a group of people and say, “How do we take the next step?”

Ray: There’s several stages: I will actually start with a couple of repeating questions. You can think of it as a series—a building series of brainstorming and visioning exercises that lead up to imagining breakthrough projects that develop new alternatives. Rather than just opposing the bad stuff.

ele: In the introduction to your seminal book, Cultural Creatives, you said that in the process of doing all the studies that provided the ground of the book, you went from being a pessimist to being an optimist.

Paul Hawken—in his recent book, Blessed Unrest—was saying a similar thing. He was astounded at how many people are out there doing [meritorious] things, and yet there’s some invisible quality to it. Even [in Boulder, a tiny city] people don’t all know each other. What is missing?

Ray: Cultural Creatives are a population of 50, maybe 60 million Americans by now. The last time I did a survey was seven years ago. But they don’t know about each other because they never see their own face in the news media, which has the modernist worldview of their advertisers, getting and spending—materialism. And they are fairly intolerant of other world views.

Both fundamentalists and Cultural Creatives—each about a quarter of the population—are dissenting from the modernist, materialist secular worldview. The media pretends that Cultural Creatives don’t exist: “Oh, they’re just a bunch of treehuggers and flighty new-agers.” And the religious right has got more attention than it deserves, in terms of its importance in society—because they look like a political threat. The Cultural Creatives don’t, so [media] ignores them.

If somebody has taken a new view of reality, of important values to have in life—saving the planet through ecological sustainability, spirituality, women’s issues, social responsibility—and the dominant tone set by the advertisers who are paying for the media says something else, then ignore ’em. They’ve got to be marginalized.

Typically, when you go into work, you check your values at the door. You don’t mention what’s really important in your life. I did values and lifestyles studies from ’86 to 2000, we probably surveyed about 150,000 people in that time. About 10,000 a year. Big numbers. And in all these surveys, a quarter of the population came out with this strong new viewpoint. Another quarter is the religious right folks, and about half are the conventional American view that you actually see in the media. But only half.

ele: And you call them “the Moderns.” And then “the Traditionals” are about a quarter.

Ray: Cultural Creatives are probably up to 30 percent.

I just got back from Amsterdam three weeks ago and they just finished a survey of Cultural Creatives there. It’s 30% in Holland, 35% in Italy, about the same in France. Germany is geared up to do their survey.

ele: And in Japan, they’re wild about L.O.H.A.S. [Lifestyles of Health & Sustainability; the term used for the Whole Foods/elephant/green/spiritual demographic].

Ray: Oh god, yes. Here, L.O.H.A.S. is just a term among business people and non-profits. But there, households say “I’m a L.O.H.A.S. person.”

ele: You’ve met Kei Izawa? He writes a series of articles about Boulder for a L.O.H.A.S. Japanese magazine.

Ray: They are going all out for sustainability, and so are the Europeans. It’s really been the Bush Administration [suppressing] that concern for the last seven years.

ele: So I’m passionate about the idea of generation. Like, “Lost generation” or “Beat generation.” You seem to be talking about a generation not based on age—a movement. It’s something I’ve wished existed for a long time. A generation that would promote ecological values, and non-New Age yet spiritual values. All the things you talk about. It seems like you see that such a generation, not dependent on age, is here.

Ray: Well then, it’s not a generation. It’s a movement.

The way people get to be Cultural Creatives is through being exposed to new social and consciousness movements that have been appearing from the 1960s, on. What the data shows is that a typical cultural creative has [been involved in] half a dozen movements—the rest of the country none, one or two.

Engagement. Cultural Creatives pay attention, read the most stuff, get the most diverse set of information, know how to use the internet efficiently. They’re paying attention. But it’s not age-graded: it’s people from their ‘70s, down to the teens.

Something may be emerging with the Millennial generation—people 15 to 25. There’s a bigger percent [of Cultural Creatives] due to exposure to a planetary world view, to more spiritual traditions than have been available than any earlier time in human history, to the fact that your children and grandchildren will live in a worse world than you did.

Another thing: this is about women’s values and concerns going public for the first time in history. Women are leading this change. If you look at the core group of Cultural Creatives, influential opinion leaders on everything green, it’s two-to-one women. Women have talked this way for a couple of hundred years—but they did it privately with their friends. Now they’re being public about it—and cultural creative men are perfectly willing to agree. The gulf you see between men and women with the Traditionals and the Moderns just isn’t there with Cultural Creatives.

A downside for women in your tribe: there’s not enough men to go around. You know you are with the Cultural Creatives when you hear the complaint, “Where are all the good men?” [Laughs] The answer is, “There’s a shortage of men who have the same concerns that you do.” So many cultural creative women are reeling in some guy and…

ele: …civilizing them. [Laughter] We did an article, ”Yoga for Men,” saying, “Yoga’s actually great: you can get in good shape. And if that doesn’t convince you, there’s a 20 to one female-to-male ratio in your average yoga class.”

Ray: [Laughs] And they probably are in great shape.

ele: Yeah. Your book was one of those key things, [like] Yoga Journal in the late ‘90s, that caused an explosion. Yoga studios doubled in number, Whole Foods and businesses like Gaiam are growing quickly. It’s an exciting time.

Ray: When you see fundamental change, it’s not one of those nice, smoothly accelerating S-curves. Instead, it’s a hockey stick: seems like nothing’s happening, nothing’s happening, nothing…then all of a sudden it goes up steeply. The conditions are being built for something new to happen.

There’s more than just the individual changing of hearts and minds—there’s the development of institutional support and the building of personal networks. It’s magical thinking in the spiritual community to say, “If I just sit on my [meditation] cushion, everything will be fine.” I’m sorry: it’s not enough. It’s a good thing, but it ain’t enough. As a 30-year meditator, let me say: it ain’t enough.

ele: Well said. That’s been one of my complaints, growing up in a strong, active Buddhist community here in Boulder—on an individual level, a lot of people are active in the world doing great things, and yet as a community, we do little except run our little centers.

And even that, we’re not always good at from a business point of view. And there’s little activism.

Ray: That’s an important point: because the building of networks and getting big friendship networks, getting support for what you’re going through is as fundamental a thing as we can ever point to. Humans are social animals and we often only do stuff that’s dramatic when we feel we have permission to do it, when we have support from our friends, when we have people around us who nod their heads and say, “Yeah, go, you do that honey.”

ele: One thing you said, which I find inspiring: Cultural Creatives are equally spiritual as they are socially active. I’d love to find out why that is the case, because it doesn’t seem to be the case with my Buddhist community.

Ray: That’s not the way I put it. In the core group, the people who are the most influential and spiritual are also the ones who are the most engaged. They try to turn their beliefs into reality. It may take them awhile, but they’re working on it.

“Green Cultural Creatives” are only green, often more secular…also less engaged. When everybody thought Al Gore was gonna be president back in ‘99, the President’s Council on Sustainable Development hired me and a big Washington P.R. firms to do a study of what it would take to get Americans to adopt ecological sustainability. Gore’s people, who are all Cultural Creatives, [laughs] said, “Let’s compare Cultural Creatives with ordinary pro-environment people.” Well, you don’t take out many people when you say “pro environment”—because about 75 percent of Americans are.

ele: Wow.

Ray: [Laughs] On the other hand, Cultural Creatives were different. We did focus groups in six different cities, then a big national survey. And what happened over and over again is that ordinary folks said, “Well, yeah, sustainability is an important idea, but it’s a techy word and I don’t know what to do about changing my life and, well, I’m sorry—I can’t engage.”

The Cultural Creatives said, “Damn it!” [Laughs] “This is important and I’m pissed off with government and big business for not doing anything about it. We’ve got to get moving.”

ele: “We’ve got to do it ourselves!”

Ray: “…and engage at the local level.”“Would you like to go to a national conference that Al Gore’s going to be speaking at in Detroit?” “Nah.” [Laughs] This was back in ’99—they didn’t see any leadership from the national level. They felt that all of politics had been bought by big business.

ele: They didn’t have any faith.

Ray: They were discouraged. They would do something at the local level. They would have a long checklist of stuff they’d tried. “I’ve got to do something, I’ve got to get engaged.”

But if you asked them, “Well, what about your work?”…It became clear that they need a logic: you’ve got to make profits in business. Since then, we’ve seen clear developments that say, “You save money when you do sustainable stuff.” But nobody knew that then. It looked like a cost-only deal.

ele: Sure. Altruistic.

Ray: …too altruistic for businesses to bother with.

It turned out to be a question of, “I’ve tried stuff and it works, therefore I’m willing to do more. I feel optimistic that things can be done—we can invent our way out of this problem!” The conventional pro-environment folks didn’t try anything. They were discouraged, there was no leadership. So you’ve got a bifurcating process of people who did stuff…did more, and saw that it worked…and did more. And people who didn’t do stuff just got the chance to be right.

Isn’t that an interesting development? It’s the actual experience of trying stuff and seeing that it’s worthwhile that makes a difference.

ele: Mmm. Politically, it seems true what you are saying: I was involved in Howard Dean’s campaign in 2004. There was almost this death wish: we all supported him because he would do something, but we didn’t think he would win, ultimately. When it came down to it, most of us jumped ship and went with Kerry, because we thought he actually might win.

Ray: Sounds like the “Clean for Gene” campaign, [Laughs] when Gene McCarthy was running.

ele: I think Obama has [run] into some of that. There’s a lot of idealism, but then people [say], “Well, Hillary has the power.” And in a lot of ways, she is not a bad choice.

Ray: I tracked the Dean campaign. The initial surge that came out of the internet connections was strong, and I was hoping that meetup.com—getting people to meet—would be enough. But it wasn’t. With internet-oriented campaigns you can do a lot of small-scale fundraising, but it doesn’t create the loyalty that’s needed for political community-building. If you’ve got people who meet face-to-face, you can follow through on the internet—but the internet by itself will not get anybody to engage and do stuff. I spent a lot of time talking to the folks at moveon.org. They said to me, “Your cultural creative stuff is great and all, but we are committed to doing one-liners that people will respond to with a click. That is the total commitment required, to send money.”

They read a one-liner and click once. That is an incredibly low-level of commitment, my friend. [Laughs]

ele: “Okay, I support that and it’ll take me three seconds, and that’s all I’m gonna do.”

Ray: That is not enough to build a political campaign or to build the trust that we’ve lost over 50 years of television in politics. We’ve got a fundamental issue in politics in the United States right now: we need to rebuild community. We’ve gotta have some trust among the people. “What is crucial to do? Let’s pledge our lives, our fortune, our sacred honor.”

That was done by a lot of people sitting close together in a room, breathing on each other, who often couldn’t stand each other personally. The founding fathers said, “We’re gonna commit, we’re gonna pledge ourselves, we’re stuck with it.” Sure, people dropped off. But they had to actually trust each other and build that sense of, “It’s time to do this together.”

Internet ain’t going to do that. Part of the reason I do community visioning is, if you can hook up ecological and community leaders at a local level in a number of different places, that has a decent chance of making something happen.

ele: Is old-fashioned community-building how Cultural Creatives are going to take the next step: influencing the Moderns and the Traditionals?

Ray: What is needed is sitting and talking face-to-face, like you and I do right now. Part of it is just convincing each other we’re trustworthy. Human beings have evolved over the last 100,000 years in small groups. We don’t do stuff together unless we can sniff each other out…in a fairly literal sense. Look each other in the eye.

ele: Yeah, you see how dogs begin to trust each other.

Ray: We’ve got to do that. Without that, not much happens. Urban life becomes anonymous, unconnected, normalist—people walk past each other in the street. It’s not enough to gather in a concert hall and then walk away. Facing the audience, giving a nice speech, raising the temperature of the audience…and then they walk away? They’ve got to look at each other, talk to each other, gather in little groups…or it ain’t gonna happen. Yesterday with the community organizing, everything was in tables of eight people. That’s about the right number for a discussion where everybody gets some air time.

ele: And then everyone gathers together at the end, and shares their findings.

Ray: The other thing I’ve done: somebody takes notes on everything that’s happening, posts it up on the walls, and every now and then you can walk around the room and see what everybody else is doing. That speeds up the process, and you still get a feel for it. And if they are all Cultural Creatives in the room, they’ll talk about the issues in the same way. There’s overlap, they start feeding on each other, realizing that, “I trust where the people around me are coming from. Let’s do it.”

When you move the conversation away from surface opinions down to a discussion of values, you get past all sorts of trivial conflicts. People start saying, “This is what’s really important in our lives.” Then the opinions shift, and what’s possible grows out of that. Start with the values, with what’s really important—then it turns out you have a basis to do something together. Yesterday, people who were meeting for the first time said, “Oh, I want to do stuff with you. It’s time to do it.”

ele: It must be inspiring, coming out of the weekend, seeing all this good merit developing. How do [Cultural Creatives] not only connect with each other, which can be hard—but should on an overall level be [comparatively] easy—how do we connect with the Traditionals and the Moderns to effect big change?

Ray: You’ve got to see that people who have different subcultures have different languages for talking about things. Right now, what’s happening in the Religious Right is that people like Rick Warren from Saddleback Church in Southern California are saying, “Listen, we’ve got to care for the planet—and the Bible is full of statements from Jesus about taking care of the poor, why didn’t I see that before?” Theologically [he’s] conservative, but on real life issues you can open the conversation with his people. He’s crucial: he’s got a pastor education service where 40,000 fundamental preachers have learned his way of doing it. They say, in effect, “If he’s going to go in this direction, I’m going to go with him because I trust where he’s coming from.” And so it becomes clear even in those die-hard fundamentalists that global warming is real. They say, “Well, why aren’t we caring for God’s creation? Do we really believe the rapture is coming next week?” So if you’re willing to shift your language, you can draw them in as friends and neighbors, fellow Americans—but you can’t expect to agree on everything.

The problem is more with the Moderns, who have bought into the selfish getting-and-spending stuff where the range of their social concerns going out from I, me and mine is like a pup tent. It drops off really fast. The fundamentalists are willing to extend their concern fairly far out—maybe not as far as the Cultural Creatives who embrace everybody on the planet.

As far as the Moderns, “What’s in it for me?” The answer may be, “Well, not much.” But on the other hand, “How about your children or your grandchildren?” Most Americans are willing to do all sorts of stuff for their children or grandchildren they won’t even do for themselves. So I ask: “If this process of global warming goes on, your children and grandchildren—not somebody else’s, yours that you’ve raised—are going to live in a much worse world than you grew up in.” That gets an immediate, “Oh, okay: I’ve got to deal with it,” response. That’s the place you start.

The problem then becomes the battle between personal ambition vs. social responsibility. Not material gain, but personal ambition. Forcing people to come to a place where they start saying, “What’s really important in my life?” When they get to be around 50, 55 and have grandchildren, a fundamental shift occurs.

One of the things that we know is that people’s values tend to freeze at whatever time they get married and have that first kid. They are pretty flexible and fluid up until then—then they freeze—then there’s a fundamental shift that happens, either the mid-life crisis, which is actually not that common, or when they have the first grandchild. You’ve got a lot of grandparents of almost every [type] who are willing to do something for the grandchildren. The “for the grandchildren” response is a major missed opportunity that we could pick up on, right now.

ele: One thing I see in my generation: people my age are founding ecological-focused companies…like Zaadz. [But] I see many of us being co-opted by the Moderns. Like Whole Foods is incredibly successful—there’s some sense that die-hard Cultural Creatives at some point say, “Well, I can make a ton of money and retire right now, because what we’re doing is so popular.”

Ray: Well, there aren’t that many culture creatives who will frame it as, “I can make a gang of money and retire right now.” The few that there are, are very visible, obviously—but the vast majority are doing something else. In fact, when I survey and talk to them in focus groups, they say, “Listen, I’ve sacrificed income to live the life I want to live.” They have a sense of having given something up to really go with what’s authentic. Now, [many of] the Moderns—about 20 percent of the population, almost as numerous as the Cultural Creatives—would change if they thought they could still be successful in life.

So the question of change becomes a personal quest. What will you face up to? Frankly one of the reasons the core group of Cultural Creatives have fewer men than women is that many men are committed to an ego-identity that’s around career success.

When will you let go of the idea that to be a good person, to be effective, you have to have career success?

When will it be, “I want satisfying, meaningful work”?

And that’s coming up for the Millennial generation. I’m curious to see, as they get into their late 20s, which way they go. When the freeze around values happens, what will they do?

ele: That’s the good news about the popularity of green—the Millennial generation is going to think, “Well maybe I can have my cake and my conscience too.”

Ray: Yeah, but having enough cake as opposed to having maximal cake is two different things. [Laughs]

ele: Good point. It’s great to have someone who’s not only inspiring but is actually researched—what you have to say is founded in reality, not just empty hope.

Ray: And not just arm-waving. What I do is action research: it’s gotta go somewhere, somebody has got to use it. So I spend my time talking to folks who want to get something done for the planet.

ele: Thank you to you and your wife, both.

For more: culturalcreatives.org

Read 3 comments and reply