Discussing Ashtanga Yoga in general terms can be tricky.

There are significant differences in its programs and instructions, usually based upon the teachers’ training, background and preferences. Nonetheless, most Ashtanga Yoga practices draw their foundational principles from the Patanjali Yoga Sutra, a Sanskrit text generally regarded as the source of Yoga philosophy.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi interprets the Yoga Sutras uniquely, apparently contradicting many assumptions underlying modern Ashtanga Yoga practices.

Ashtanga Yoga today

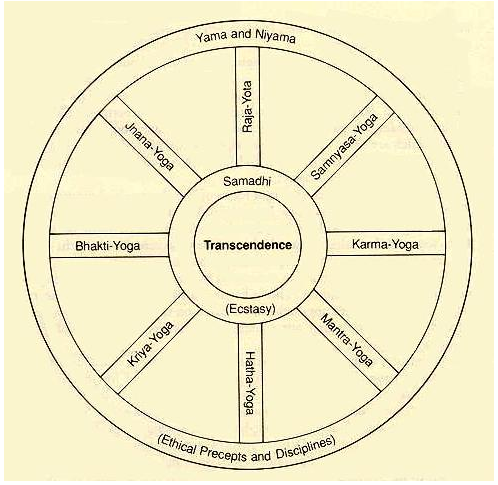

The Yoga Sutras describe eight (ashta) limbs (anga) of yoga (ashta + anga = ashtanga). Most commentators feel that these include four external cleansing practices (yama, niyama, asana and pranayama), three practices for “internal cleansing” (pratyahara, dharana and dhyan), and samadhi, most commonly understood as the experience of the inner Self.

Practices usually consist of a vigorous, athletic series of asanas (yoga postures) along with various pranayamas (yogic breathing exercises) to cleanse the body and build flexibility, stamina and strength. In addition, many practices at least nod toward behavioral purification practices that are also derived from the eight limbs. One might, for instance, be encouraged to always speak the truth (satya — one of the five yamas), to maintain an attitude of non-violence (ahimsa — also one of the five yamas), and to control greed by minimizing (or even eliminating) extraneous possessions (aparigraha). These practices are thought to lead to yoga, though what that means is subject to differing interpretations.

Maharishi, however, holds that the Yoga Sutra does not advocate a practice—it is not a how-to manual for students wishing to pursue yoga. Rather, in his view it is a description of the state of yoga. To understand Maharishi’s interpretation we need to first consider his definition of yoga, principally regarding the distinction between state of yoga and path of yoga.

The state of yoga

The second sutra of the Yoga Sutra defines yoga as follows: Yogash chitta-vritti-nirodhah. Normally, yoga in this context is taken as a practice—part of the so-called path of yoga—and thus the sutra is usually translated something like: Yoga is the restriction of the modifications of the mind, clearly suggesting a practice for attaining a quieter, more peaceful state by inhibiting mental activity. Maharishi, however, disagrees, holding that a better translation is: Yoga is the complete settling of the activity of the mind.

It’s a subtle distinction, but monumental in its implications, for Maharishi is suggesting that the yoga of the Yoga Sutras is the goal and not the path — it’s not something that you do (like restraining the mind’s activities), it’s a state of inner awareness that you experience.

Maharishi defines this inner state of yoga, the goal of yoga practice, as the experience of a transcendental field of pure intelligence, found deep within; it is an infinite “ocean” of creativity, intelligence, happiness, and peace, our inner Self. In the Upanishads this infinitely blissful intelligence is often called Atma, and when we experience it we are enjoying yoga—the union of our individual intelligence with the cosmic inner Self.

What does this mean for Ashtanga Yoga? In Maharishi’s view, Ashtanga Yoga as described by Patanjali is not a practice for experiencing yoga, it is a detailed and comprehensive description of the eight fundamental characteristics of the state of yoga. In this sense, it is more a philosophical description than a practical guide.

This presents us with many questions, as the eight limbs include terminology we normally associate with yoga practice. But in his analysis, Maharishi is not rejecting the procedures that are an integral part of our yoga tradition. What he is saying is that terms such as pranayama and asana, while referring to yoga practices in much of the Yoga literature, are used in the Yoga Sutra to describe characteristics of the state of yoga. This is not shocking, it is commonly understood that Sanskrit words often bear many layers of meaning—a quick glance at any Sanskrit dictionary will reveal a multitude of meanings for virtually every word.

With this in mind, let’s examine a few of the limbs just to get a feel for Maharishi’s point.

Take the five yamas, for example (yama is the first of the eight limbs). Trying to observe satya (truth) is noble, as is endeavoring to practice ahimsa (non-violence). And of course everyone wants to be less covetous (aparigraha), and to never take others’ property (asteya). But in Maharishi’s view practicing these will not bring you to the state of yoga. For that you have to go deep within and experience the inner self, the source of our creativity, intelligence—our lives. Without that experience, it will be difficult to rise to enlightenment, which he describes as a permanent state of yoga in which the infinite, unbounded, eternally blissful inner Self is lived in every phase of outer life. For that, Maharishi recommends his Transcendental Meditation® practice, for it enables anyone to easily and effortlessly take the awareness deep inside to experience the blissful and peaceful state of yoga.

Maharishi supports his thesis by pointing out that ashtanga (ashta + anga) is Sanskrit for eight limbs, not eight steps, and that ashtanga yoga therefore cannot be a series of steps for reaching yoga. He reasons that limbs are by nature extensions, and that just as limbs grow automatically with the body’s development, the eight limbs of yoga grow as yoga develops in our lives—as our infinite, unbounded inner intelligence becomes increasingly lively outside of meditation, we naturally and spontaneously become more truthful (satya), less violent (ahimsa), more pure (shaucha), more content (santosha), less attached to objects of senses (aparigraha), more stable and solid (asana), capable of spontaneously holding on to the experience of yoga outside of meditation practice (dharana), etc.

These are just a few examples, and those familiar with Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras and with the Sanskrit language may have more questions.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editorial Assistant: Guenevere Neufeld/Editor: Bryonie WIse

Photos: Elephant Archives

Read 19 comments and reply