Another year, another lovely Passover with the family has come and gone, yet some of the lessons from the seder remain in my soul and demand further inspection.

For the past couple of days, I have spent each morning unrolling my mat and using yoga as a vehicle with which to explore and learn the lessons of the seder.

I have always been a big fan of this holiday, and while I don’t considered myself an expert on the story of freedom narrated throughout the night of the seder, I am (at the very least) a good student of it.

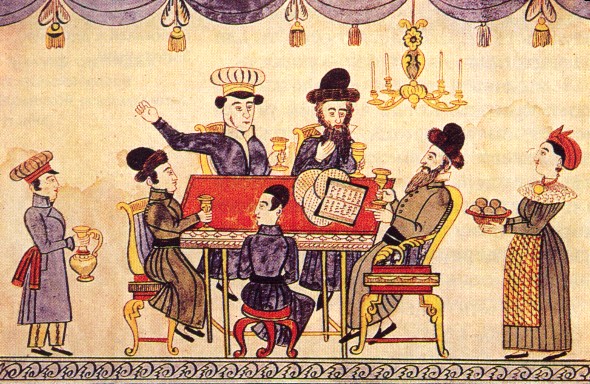

During seder, it is customary to tell the story of of Moses, who, aided by God, was able to free the people of Israel from slavery. On that night, the youngest person in the room must ask four questions to the company:

1) On all other nights, we eat either leavened or unleavened bread; why, on this night, only unleavened bread?

2) On all other nights, we eat all kinds of herbs; why, on this night, only bitter herbs?

3) On all other nights, we need not dip our herbs even once; why, on this night, must we dip them twice?

4) On all other nights, we eat either sitting up or reclining; why, on this night, do we all recline?

The man (or woman) leading the seder addresses these questions by telling a story about four children of four different constitutions —one child who is wise, one who is wicked, one who is simple and one who does not know how to ask a question.

I thought I understood why we were told this story every year. I thought I had a full grasp on why we talk about the plagues, hide the afikomen, drink several cups of wine, eat the unleavened bread and the bitter herbs, and wait for Elijah to arrive as a messenger of things to come.

I had never considered the fact that I had no earthly clue as to why we asked those questions. The questions had always seemed dreary and useless to me. The redundant nature of asking them year after year was a bit over the top, and it seemed to me that anyone who had attended Passover seder for more than 16 years in a row would know the answers by heart.

To be honest, the four questions explained by the story of the four children never made sense to me, or really mattered—in my estimation, I knew all there was to know about the story, and was bored with hearing the same explanation year after year.

This year, however, something interesting happened.

The morning after the Passover feast, I unrolled my mat, and as soon as I sat down to breathe—before I even moved an inch— it hit me!

I am the four children.

We are all the four children.

I realized that at certain times in everyones life, we have each acted as each one of these children—the wicked, the simple, the ignorant and the wise.

The wicked child asks, “What does this drudgery mean to you?”

In asking this question, the wicked child is making a clear statement— that what others are doing is not his concern, and that he is in some way above, beyond, or simply separate from those around him.

Like the wicked child, at different stages in our lives, we have each been wicked in thinking that what is important to others should not be of any concern to us —that we are in some way better than—or simply separate from—others around us (when in reality, we are all at our very core one and the same).

Through my own practice of yoga, I have been able to learn that the very idea of “separateness” is just an illusion, and that it can be dispelled when we are willing to realize that we are all essentially one and the same. I have been able to learn that loving one another, empathizing with one another, and not harming (ahimsa) one another can change the way we relate to ourselves and to others.

I realize that one person’s pain and suffering affects the whole of humanity, and through the questions of the wicked child, I understand why. Unfortunately, I do find that in many ways the wicked child in me utilizes new ways to judge and create a barge between other beings and myself.

If we can stop asking, “what does this drudgery mean to you?” we can start to opening ourselves up to more compassion. We can open up to grace, allow ourselves to become connected to all creatures, and we can stop feeling separate from them.

The simple child asks, “What’s this?” with no understanding of what is going on around him.

In many ways, I feel I am this child more than any of the others. I often find myself so deeply caught up in my own life, that at times I can lack awareness and knowledge of what is going on around me and in other people’s lives.

But what if we made an effort to stay connected, to stay grounded, to listen, to learn and to be willing to always keep a beginners mind? I think that adding a sense of curiosity (in my case, the same sense of curiosity that I am filled with when learning about my yoga practice), can help us see the world as a classroom, and can inspire both a never-ending willingness to learn, and a desire to share what we have learned with others around us.

The child who does not know how to ask a question is simply given an answer.

I think we can all admit to either lacking the words, or sometimes lacking the willingness to learn how to relate to others. In a world that can make us slightly apathetic, we can become complacent, and in that complacency lose our want for knowledge and our ability to learn (something, that I think a beginners mind can also help with).

The true dispelling force of ignorance is knowledge.

In yoga, we learn that cultivating a knowledge of the self will lead to wisdom and maturity. When we step on our mats, we embark on an internal journey, we allow our breaths to carry us into a state of meditative flow, and we allow ourselves to go deep inside our bodies, minds and spirits.

This, in turn, allows us to come face to face with who we are at our very core. The more we practice, the more we are able to connect with ourselves and those around us. In this connection, we find a type of learning and growth that can help dispel the cobwebs of wickedness, simple-mindedness, and ignorance in our lives.

Which leads me to the wise child—the child I hope I can become through my practice.

This child is understanding and empathetic, and has reached a point of ultimate understanding (in yogic terms, we call this samadihi). This child has been able to draw energy from the roots of the yoga tree, and knows the fruit of his efforts are the knowledge and wisdom of connection. Through this process, the wise child has been able to find a sense of union with the divine, and has achieved the ultimate goal of the yogi.

This passover seder i was able to learn a lot about myself, my yoga practice and my four inner questioning children. As I allow my practice to grow, I have decided that I will allow all four children within me to learn and evolve— to open to grace so that, when the time comes, they may evolve into one, loving, wise child.

“Who is wise? He who learns from every person.” (Pirkei Avos 4:1)

Indeed it is fitting that the classical title for a Torah scholar is ‘Talmid Chacham’—a wise student.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editorial Assistant: Brandy Mansfield/Editor: Bryonie Wise

Photo: Wikicommons

Read 0 comments and reply