Before I get started, let me ask you this: are you the author of your thoughts?

Keep your answer in mind.

This past August, I went to the Heritage Festival in Edmonton and for a day, I had the pleasure of immersing all my senses in the kaleidoscope of proud cultures. I stopped to marvel at the enticing display of Egyptian artifacts, and as I read the posters explaining some of the symbolism, something caught my attention: there were six senses represented in the Eye of Horus.

To my greatest surprise, I found out that in ancient Egypt (as well as in Buddhism and other Indian epistemologies), thought was considered a sense!

And not even the most important one, coming in fourth after touch, taste and hearing. Something about this information was a bit unsettling for me, but I couldn’t quite figure out what. I kept it in the back of my mind, and a few months later as I started reading the Yoga Sutras, it came back as an epiphany.

I’m sure most of us have heard of the virtues of clearing and quieting the mind. In fact, doing so is a defining aspect of yoga, as given in Sutra 1.2: yogaḥ cittavṛtti nirodhaḥ—“yoga is the cessation of movements in the consciousness.” I’m also sure that for most of us, the practical attainment of that idea is somehow slightly out of reach (or comes with great effort), but I think I found the way in.

To really grasp the implication of seeing thought as a sense, we should get clear on what a “sense” is.

Google’s definition for it is “a faculty by which the body perceives an external stimulus,” so by its very nature, a sense (or our experience of it), is reactive to an external event, and hence is dependent on it. Something happens in the external world, we make contact with it and pull it in by one of our faculties: sight, smell, hearing, taste, touch, or thought.

We are so used to our senses that their mechanics seem easy to grasp: a melody is played, it enters my ears, my ears communicate to my brain, and voila—I hear something.

Here’s a question: does the fact that we hear the melody mean that we made it?

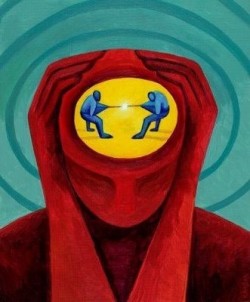

And I do mean made it—composed it, or authored it? Chances are, you don’t think of yourself as the creator of the melody you heard. If your mind is another faculty of sense (just like your ears), how is it that you think you are the creator of what enters it—like “your” thoughts?

We seem to have this grand misconception that we are the authors of our thoughts, which causes us to embrace them, ever so defensively, as true.

Seeing thought as a sense really changed the way I perceive my relationship with what goes on in my mind.

Rather than giving it a certain elevated status as something that comes from within with great intelligence, I started seeing it as something that is brought on by external stimuli: in the same way that light catches my eye, noise engages my hearing, or people, words, and events trigger thought in me. When we touch an ice cube, it’s clear to us that the resulting sensation of cold wasn’t created by us, ourselves—so, why see thought as ours?

Try this exercise: every once in a while, when you catch yourself on board of a train of thought, stop and consider how you got there, what started it, and whether it’s worth staying on it.

I noticed that my thoughts, more often than not, really are a response to something external: the appearance, demeanor or clothing of a passer-by that reminds me of the 90s, Ace of Base, then how I went to their concert, and who I was with, how I miss that person, and a conversation we had that one time.

That thought continues until something else I encounter triggers a different train of thought and takes me in yet another direction.

It seems that more often than not, rather than being the author of my thoughts, I am a mostly a receiver.

And in those situations I contribute to, at best, only a half of the thinking—in that sometimes, given enough presence and awareness, I get to “stir” it: I can choose whether I take someone’s compliment on my appearance as pleasant or as an objectifying insult.

Moreover, considering the fact that our mental patterns and responses are shaped to a large degree by our cultures, upbringing, past and present relationships and social norms, to a point of us being somewhat on autopilot, taking credit even for a half of the thinking process seems a bit too arrogant.

In fact, there is a whole field of embodied cognitive science, which in its radical forms removes deliberate thinking from the equation all together, and sees all complexity in human behavior as a product of interaction between a body and its environment (i.e. we are completely reactive in everything we do).

When the above dawned on me, I had a bit of an identity crisis.

Luckily, it’s not all that bad: we still manage to have productive, creative, original and truly individual thoughts, beliefs, and opinions. Reducing the grandeur of our minds to a set of reactive experiences would be a gross understatement and an immense disservice to humanity.

Seeing thought as a sense puts more importance on the stimuli that evoke it: what’s worth causing thought in us?

Yoga Sutra 1.7 reads: pratyaksa anumana agamah pramanani—“correct knowledge is direct, inferred or proven as factual.” The relevant aspect of this Sutra for this discussion is that correct knowledge (i.e. truth) comes from within, or at least has an intimate relationship with conscious, present deliberation and discernment.

In other words, if a thought in your mind wasn’t elicited by you, or isn’t of service or deliberate interest to you—don’t think it. Take charge for the thinking process, so that you’re aware of what is causing thought in you.

It’s a lot easier to notice what’s engaging our other senses: we generally know that the texture on our skin is of the clothes we’re wearing, that the sound in our ears is of the wind rustling through the trees. But there is a difference between the red dot projected onto the screen by a laser pointer of the presenter, and one aimed at the heart of someone to be shot; between a loving hug from your mom, and a restraining hold of a mugger.

We have a lot to gain from distinguishing desirable sensory perceptions from those that are threatening or unserving, and the fact that thought is a sense that takes an extra step of meta-awareness doesn’t make it any less important to explore, bring attention to, and clean. If you taste something unpleasant, you spit it out. If something undesirable gets on your skin, you wipe if off.

Why doesn’t your mind get this maintenance?

Why doesn’t your mind get this maintenance?

Being selective and discriminative with what enters the mind and inspires thought is of paramount importance. It sounds like a simple principle, but somehow the hygiene of the mind is never taught, and is seldom practiced.

It takes immense effort and deliberate awareness to see a train of thought and say “nope, it’s not mine, I won’t think it.”

This really made me see the importance of meditation: it’s the hygiene of the mind.

When the mind is cleared of its reactive nature and allowed to come to silence, we return to ground zero—the pristine core, the well of inspiration connected to so much more than your daily life.

Putting thought in the context of a tangible sense makes it so much easier to understand and take care of. We go to great lengths to please our other senses: we wear perfumes and light scented candles, we listen to music we like, we treat ourselves to decadent deserts. But when was the last time you pleased your mind with a truly stimulating conversation? Gift it with an amazing book? Allowed it to be inspired?

If you hadn’t had a single shower in as long as you haven’t meditated (or practiced mental well-being and hygiene in any other way be it prayer, journaling, cathartic conversation, introspection, etc.), you’d have a good approximation of what your mind looks like.

Imagine that for some people, that’s the duration of their whole lives!

When thought and contemplation is allowed to come from within (rather than be occupied by reactions), there is a certain clarity and wakefulness; a sense of ownership of our own consciousness.

Granted, I don’t think we can completely eradicate reactive thought, nor do I think we should.

This very line of thought was inspired by a poster I saw at a fare; the desire to express it in this article came from a conversation with a friend. In fact, I think that depriving ourselves from such an intimate interaction with our environments would take away such an important part of being human.

However, I do think we need to pay close attention to what enters and stimulates our minds, and treat them with as much care and discernment as we treat our other senses—if not better.

Ever since I started thinking of my own mind as a sense, it’s been a whole lot easier to keep it clean: after a few months of such deliberate attention to it, I sometimes find myself at a loss for what to think about! There is a surprising, tangible feeling of choice—I get to choose what entices my mind next.

Perhaps this way of thinking about it can unlock that inspired serenity for you too.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editorial Assistant: Chrissy Tustison/Editor: Bryonie Wise

Photos: Flickr

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 1 comment and reply