I recently contemplated three big questions about SBNRs.

Recently, I was one of five panelists for a discussion called “Spiritual But Not Religious: What Exactly Does That Mean?” It was cosponsored by the Southern California Committee for a Parliament of the World Religions and All Paths Divinity School, and the format was this: Panelists were given three questions in advance and asked to deliver three-minute responses to each. Here are the answers I prepared:

Obviously, there is much more to be said about the Spiritual But Not Religious (SBNR) phenomenon, but I was asked to stick with the 3 questions asked.

1. From your personal experience how do you explain and assess the apparent move away from organized religion and the emergence of the SBNR phenomenon?

Recently, Stephen Colbert interviewed a journalist who said that a secularized form of Buddhist meditation helped him overcome panic attacks. “But will it help you when you’re burning in hell?” Colbert quipped. That’s satire, but it captures one reason people have left organized religion and turned to non-sectarian spiritual practices.

The SBNR phenomenon says that the innate spiritual impulse knows no boundaries, and it won’t be denied even when conventional religion turns people off with dogma they find irrational, hypocritical, or socially divisive. It also says that when organized religion fails to satisfy the longing for transcendence, people will turn elsewhere.

I think of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau as America’s founding SBNRs. But, while SBNRs have always been with us, their numbers exploded when the baby boomers came of age in a world of great diversity and easy access to new sources of information, especially the spiritual traditions of the East.

That SBNRs choose to cultivate their spiritual lives outside the borders of mainstream religion does not mean they are necessarily anti-religious or religiously indifferent. For many of them, It’s more accurate to say they’re anti-exclusivism, or anti-commitment. They may in fact learn from all religions, especially Westernized versions of Hinduism and Buddhism, which would make them more multi-religious or polyreligious than nonreligious. They just don’t commit to one single tradition, and they explore religious teachings selectively.

2. How do you respond to the perception (of some) that SBNRs often are narcissists and hyper-individualists unaccountable to any community?

First, let’s stipulate that there is probably as much variation among SBNRs as there is within any religious category. We have to be wary of generalizations.

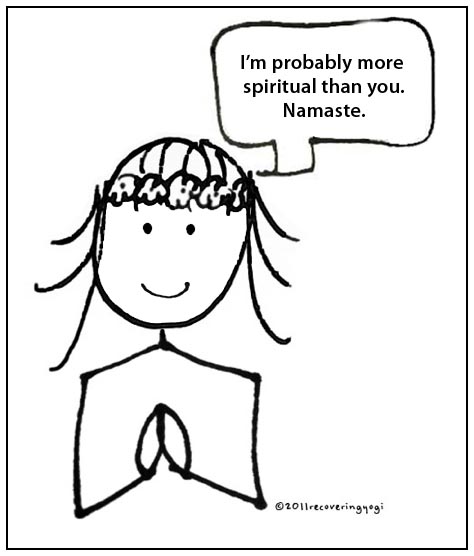

That said, in my experience, many SBNRs are narcissists and hyper-individualists. But the question assumes that people who identify as religious are not narcissists andare accountable to a community. I’m not sure that’s true. In fact, I’m pretty sure it’s not.

The more important issue for me is depth. If we could measure the depth of one’s spiritual experience and commitment, we just might find that SBNRs are, on average, as (or more) committed and as (or more) grounded in deep experience than the average person who calls him or herself religious. As someone once said, sitting in a church and thinking you’re spiritual is like sitting in a garage and thinking you’re a car.

In other words, it’s a huge mistake to label SBNRs as self-involved narcissists, as many critics do.

It’s also a mistake to say they’re trying to create their own one-person religions. Setting aside the fact that we all do that to one degree or another, it’s not that SBNRs reject guidance. The serious ones actively seek out wisdom, not just from spiritual traditions, but also from psychology and other secular and scientific sources. They are, as one anthropologist put it, “the student and beneficiary of all traditions, and the slave to none.”

The absence of community is a real challenge, and many SBNRs acknowledge that. Some try to create community informally, associating with like-minded friends, starting small leaderless groups, hanging out in non-sectarian places like yoga studios, meditation centers, and alternative metaphysical institutions. It remains to be seen whether durable communities arise, and whether SBNRs will invent standardized rites of passage—weddings, funerals, etc.

3. What do you see as the most significant contributions of SBNRs to a) the spirituality of the future and b) society at large?

I think the SBNR phenomenon is playing a leading role in a massive re-evaluation and redefinition of religion for a pluralistic age. It shows that it’s possible to have a deep, authentic, meaningful spiritual life outside the boundaries of conventional religious institutions. This is liberating news, and it is consistent with the American ethos of freedom and independence.

It has also brought to widespread attention, 1) the substantive difference between what we call spirituality and religion, and 2) the universal need for inner transformation and transcendence. These realizations, coupled with the influx of spiritual practices from the East, have begun to transform the Abrahamic religions. We see a surge of interest in contemplative Christianity, Jewish mysticism, and Sufism. This democratization of the esoteric aspect of religion might make religions deeper, more complete, more balanced, less rigidly dogmatic, and better able to fulfill their adherents’ spiritual needs. If mainstream religions get the message , they might even lure some SBNRs into the fold. But the clock won’t be turned back.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Jenna Penielle Lyons

Photo: elephant archives

Read 1 comment and reply