Arjuna’s Dilemma

The great Sanskrit epic Mahabharata tells the story of a bitter rivalry between factions of a royal family, which according to tradition ruled the kingdom of Hastinapura over 5,000 years ago. After years of failed diplomacy and ongoing hostility, the two sides finally faced off on the famous plain of Kurukshetra, each supported by vast armies assembled from all over the Indian subcontinent.

On the day of the great battle, the troops were spread as far as the eye could see, poised to begin what would become an eighteen-day ordeal, unprecedented in its carnage. As the armies were set to engage, an extraordinary event took place.

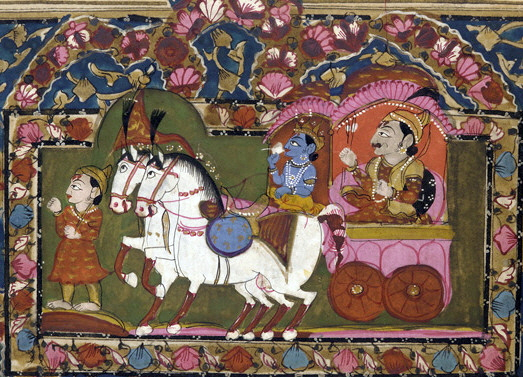

One of the Mahabharata’s great heroes, Arjuna by name, asked his charioteer to drive him between the opposing forces so that he could survey the field and assess his troops’ prospects. Arjuna was the greatest warrior of his time, famous for his bravery and unparalleled skill in archery, and honored for his dedication to upholding the principles of dharma—righteous behavior.

As he stood in his chariot observing the armies, Arjuna became disheartened. He was a kshatriya—a member of the caste that protected and administered society—and so his duty lay in conquering his villainous enemy, whose immoral and unlawful conduct had undermined society for many years. But the opposition included many whom he held dear, particularly his teachers and an assortment of relatives.

To kill them, regardless of which side they were on, seemed wrong and contrary to accepted conventions. His mind was clear, but his feelings were strong, and the thought of fighting against those he loved was breaking his heart. He expressed great sorrow to his charioteer and then threw down his bow, refusing to fight. He felt overwhelmed and his problem seemed insoluble.

Arjuna’s charioteer, however, was none other than Lord Krishna, famed throughout Sanskrit literature for his enlightened vision. Lord Krishna’s apparent role was to provide tactical advice while guiding Arjuna’s chariot, but more importantly he was to reveal the deepest principles of life and living to Arjuna, which he accomplished in the moments before battle. Their conversation is recorded as the 700 Sanskrit verses of the Bhagavad-Gita, often considered the soul of yoga philosophy.

Be Without the Three Gunas

Lord Krishna’s teaching presents a comprehensive study of yoga philosophy, but according to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the founder of the Transcendental Meditation program, its essence can be summarized in just two verses. (2)The first may appear a bit obscure, but it is an essential part of Lord Krishna’s discourse:

…Be without the three gunas, O Arjuna, freed from duality, ever firm in purity, independent of possessions, possessed of the Self. (2.45)

The three gunas are traditionally understood as the most basic forces in nature, responsible for everything; the whole universe is said to emerge from their interplay. Be without the three gunas, then, encourages Arjuna to go beyond the material universe to something even more fundamental. (2)

But what is beyond matter? You might think that the mind, intellect, and emotions are beyond the three gunas, but even these are said to be within their influence. Apparently Lord Krishna refers to something even more fundamental, a transcendental reality that is beyond even space and time. Maharishi describes this as the “unmanifested reality of all that exists, lives, or is,” (1) an infinite ocean of consciousness, pure wakefulness, pure existence, which creates and administers everything throughout the universe. And though this field of intelligence never changes, all changes and transformations take place within it. (1)

Most commentators in recent centuries have felt that Lord Krishna was encouraging Arjuna to adjust his attitude—that to “be without the three gunas” means that he should distance himself from the events and people around him. In this way, his mind would not be bound to the material world and he could (supposedly) enter battle without remorse. But in Maharishi’s view, this interpretation is antithetical to the entire teaching of the Gita.

Regardless of noble intentions and aspirations, changing one’s attitude does not bring us beyond the three gunas, for a new mood, attitude, or philosophy is still very much under their sway. Instead, Maharishi writes, Lord Krishna was advising Arjuna to take his awareness to the infinite, pure consciousness, which can be located within each of us—the transcendental reality that is, by definition, the one element of life beyond material forms and phenomena. (2)

To experience this state, Maharishi emphasizes, one must have a technique to take the awareness deep inside to the source of thought. For this he taught the Transcendental Meditation practice, which allows the awareness to effortlessly and easily go beyond the field of thought and settle into this transcendental consciousness, the inner Self. This level of life is unavailable via attitude or predisposition. (2)

Established in Yoga Perform Action

In the second verse under consideration, Lord Krishna continues his teaching:

Established in Yoga, O winner of wealth, perform actions having abandoned attachment and having become balanced in success and failure, for balance of mind is called Yoga. (2.48)

This verse has also generated a variety of interpretations.Yoga-sthah (established in yoga)is often thought to mean something like be firm in the practice of yoga. As part of this understanding, one should behave in certain ways: One should abandon attachment to the material world and maintain a more balanced attitude toward success and failure (and by extension all of the pairs of opposites), and this will supposedly bring a more even state of mind.

But in Maharishi’s view, yoga in this verse is not a practice—it is not something you do—it is the experience of one’s inner Self, the infinitely blissful, infinitely intelligent pure consciousness that is beyond the three gunas. It is the state of yoga to which this verse addresses itself, not the yoga practices—Lord Krishna is describing the goal, not the path. (3)

This is not to say that the asanas(yoga postures) and pranayamas (yoga breathing exercises) are not yoga. They are part of the path of yoga, which includes those techniques and procedures that support the experience of the state of yoga, the inner experience of the Self.

Maharishi further explains that over time, this inner state of yoga becomes increasingly a part of waking experience—it becomes a constant feature of life, a state of enlightenment. That is what Lord Krishna means when he says established in yoga—he is describing that state of consciousness in which the inner experience of yoga is never lost, even during one’s normal active life.

The Practical Benefit of Experiencing the Inner Self

The value of becoming established in yoga is obvious—life in happiness, with full creativity and intelligence. But there is an additional characteristic that explains why Krishna taught this to Arjuna in his moment of sorrow. The pure consciousness within is not only the source of our thoughts, feelings, emotions, and creativity, but it is also the most fundamental level of nature’s functioning.

According to Maharishi, this non-changing, infinite intelligence is the home of all the laws of nature, the inviolable principles that structure and administer every level of life. When the birds migrate north, when the flowers bloom and the waves come crashing onto shore, they are acting in accord with laws of nature. And when we establish our awareness in yoga, we are enlivening our own connection to all the laws of nature, so that they begin to work for us to guide us in our thoughts and actions, and in our progress to enlightenment. (1)

In Maharishi’s view, this is the essence of Krishna’s instruction to Arjuna. Lord Krishna advised Arjuna to go deep within, experience the transcendental inner Self, and with his awareness established on that level then he would be able spontaneously act most appropriately. And then his decisions would be spontaneously more appropriate, more life-supporting, more evolutionary, and more successful.

References:

- Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Science of Being and Art of Living, (New York, NY: Plume Publications, 2001. (Original work printed in 1963.)

- Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. (1967). Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation and Commentary, Chapters 1–6. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

- Sands, W.F. (2013). Maharishi’s Yoga: The Royal Path to Enlightenment. Fairfield, IA: MUM Press

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Apprentice Editor: Ola Weber / Editor: Catherine Monkman

Photos: Wiki Commons

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 10 comments and reply