This article is the third in a series with Walking in Beauty: Why Higher Education Should be Indigenized and Indigenized Education is All About Relationships.

Entering the Red Lodge does not imply that you become an Indian. We are not living a fantasy here. It means to expose and embrace yourself as you are, with all that you are, independent of the color of your skin, to be disposed to hear, to unveil to truth, to learn true courage, and to deepen your sense of spirit. ~ Ohky Simine Forest

What is it that impedes the development of a relationship between teacher and student, or between any two beings for that matter? What else but fear.

And what allows them to grasp their shared nature and destiny, and to join together? What else, but love.

As I began to walk the Red Road, seeking deeper understanding and clarity about what it means to teach, I began encountering sources of fear which served the primary function of training the student to accept subordination in the process of learning.

I had always sensed this about my own educational experience in the public school system, which is why I mistrusted it.

Irrespective of the subject-matter being taught, there seemed to be a deeper purpose behind the exercise; namely, the training of the student to sit still and listen, have fear of the teacher’s power to punish or judge, accept whatever was being presented as true, and to want to please the authority, please the teacher.

Last semester when I asked students about what bothered them the most about their educational experience, one of them said this:

“Throughout my years taking college courses traditionally, my relationship with my professors have essentially been to “do as you are told”. This method of teaching does not necessarily inspire individual thought, but rather a calculated black and white rubric as to how to fulfill the expectations and overall desire with the interest of my professor in mind rather than myself. To me, this does not necessarily promote growth or inspire learning.”

As I reflected on the process of deepening my relationship with my students, I realized that I had to examine these power relations and figure out how to transform them.

This is a key aspect of indigenizing education: we are called to deeply examine our concept of power, of how power operates in the class room to maintain the kind of society we currently live in, and how a different power dynamic would open up space for a retrieval of traditional forms of peace, trust and partnership.

How do you transform something beautiful and effortless into something boring and painful?

Every time—which is all the time—I am asked by a student, “What do I have to do to get a good grade for your class?”

I feel sadness and compassion for this young mind who has already been so deeply indoctrinated by her schooling, that she has almost no interest in actually learning anything. And of course the student who is asking this is ironically the one who is considered the best student, the “A Student.”

I was struck last semester by a particularly poignant moment I witnessed before class, when I overheard two students talking about what courses to take the following semester. I heard one of my students—a very bright, motivated, creative student, mind you—say to her friend something to the effect of, “Oh you should take so-and-so’s class, you don’t have to do anything.” I was quite struck, thinking to myself, but this is a really bright student who loves to learn! What is going on here?

It’s a dirty secret of higher education that many students do not like kind the experience of being in a classroom.

This is not because they do not want to learn or that they are lazy, as is assumed by many professors, it is because they do not want to be programmed.

While in some important respects modern education fosters freedom of thought through training in literacy, in other ways, it requires strict limits on both freedom of thought as well as self-knowledge. This is because one of its primary jobs is to teach, through the medium of the classroom itself, a certain concept of power—one which is at odds with our purported democratic values.

It has become apparent to me that students are never asked to “buy into” the learning project, or to accept that the terms and methods used make sense or are optimized for real learning. To do so would be to treat them as equals. To treat students as equals in the process of learning would be to teach equality itself, and therefore democracy.

Could it be that our educational system was consciously inspired by a fear of too much democracy?

In fact, democracy is not a creation of western culture but a form of society first practiced by native peoples.

Both Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson knew that the oldest, and most successful participatory democracy in the world was not ancient Athens, but rather the Haudenosaunee, the Peoples of the Six Nations, or what the French called the Iroquois Confederacy.

Unlike ancient Athens which was xenophobic, maintained wealth inequality, had imperial ambitions and enslaved its women, the Haudenosaunee was a truly egalitarian, matricentric society where war was put to an end by a Council of Grandmothers.

Yes it’s true, the so-called American democracy was inspired by indigenous knowledge, and will likely succeed only if it nourishes itself more authentically from a true, spiritual connection to Mother Earth.

Looked at unsentimentally, it is not surprising that our political and the educational systems were designed to maintain strict limits on the growth of democracy.

Too much democracy and the majority will vote to correct the inequality of wealth endemic to the current system from its birth. And too much sexual equality would undermine the dominant patriarchal psychology that supports a military industrial empire still bent on world domination.

Maintaining the hierarchical, “command-and-control” pyramid of power at the foundation of western industrial society requires the mass production of a certain kind of authoritarian personality—a person who lives in fear of authority, and strives to conform their beliefs to their leaders.

I now share the indigenous view that authoritarian structures dishonor human relationships and impose unnecessary limitations on the development of Self-knowledge. An indigenous perspective does not use education as training for mental slavery for the reason that indigenous education is not designed to serve empire, it is designed to bring into existence authentic human beings.

If we look more deeply at the basis for such radical, fundamental differences between modern and indigenous education, we find contrasting notions of power.

In the modern western model, students are trained that “success” is having power, and that power is a kind of control—control over others, over resources, ultimately over Nature herself. And the power that the teacher has to judge the student is a reflection of the power that the white man’s culture believes it has, and must continually extend, over Mother Earth and her many Beings.

The indigenous concept of power is diametrically opposed to the modern western view. In Ohky Simine Forest’s words, “power for the Red people is more than a concept.”

It is a knowing. It is our very life itself. It is to fight for our veracity, for the truth beyond spirit. It is circular power, the capacity to meet ourselves with honesty, to walk with our fears, to fight face to face with our illusions and defeat them forever, to hear the language of spirit, to talk and to touch the heart of the people, to love the Earth in an infinite, unconditional way. Power for us is the ability to recognize our own mistakes with great humor. Real power is respect for the dead, for the elders. It is to consider ourselves a sacred temple in which the Spirit can live.

[Dreaming the Council Ways (Samuel Weiser: York Beach, 2000), 19.]

This view of power sees strength in the ability to surrender to truth, to Spirit, not force one’s will on the world.

Assuming one believes this is the way to go in education, it naturally raises the question as to how one begin to balance out the modern system with such a beautiful and radical vision of freedom.

What began to happen as I removed these sources of fear from the classroom and actually started to treat my students as equals? Something very exciting…

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Apprentice Editor: Carrie Marzo / Editor: Renée Picard

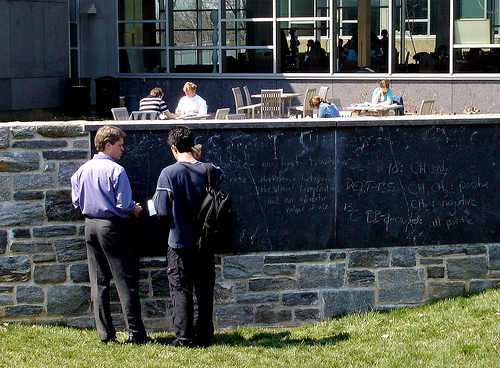

Photo: EAWB / Flickr

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply