Editor’s note: Elephant is a diverse community of nine million readers and hundreds of writers (you can write too!). We are reader-created. Many blogs here are experience, opinion, and not fact or The One Right Point of View. We welcome all points of view, especially when offered with more sources and less invective, more frankness and less PR. Dislike this Op-Ed or opinion? Share your own take here.

Organized religion has the capacity to cause great detriment to the soul.

Unless we learn our own souls and experience the depth of spirituality for ourselves, we set ourselves up to be tossed about by the waves of opinionated teachings that could cause undue spiritual confusion and needless suffering.

My own awakening came in the form of the last joke I would ever listen to from the Southern Baptist church and the start of a painfully beautiful discovery of true spirituality. The sermon was on the epitome of womanhood, the Proverbs 31 woman, who apparently had servants.

“So women today, you have no excuses,” the voice from behind the pulpit goes, “because you still have servants today. They are called ‘dishwasher’, ‘oven’, and ‘washing machine.’”

Then people laughed.

But to me, it was not at all funny.

It was, rather, an indication of a problem that stretches much deeper than any religion, denomination, or church particularities.

It is a problem of denial. The sermon itself made me realize my silence was the result of my own hands being wrapped around my own throat, and that asphyxiation felt like a punishment, but it was really just a symptom of my need to stand up, turn, and walk away.

See, where I’m from in the deep South, church and culture are synonymous.

Hands wrap tight in Mississippi, even today.

The 1950’s and 1970’s are the same as 2014 in small town Mississippi where the KKK still holds meetings a good twenty minutes down any rural road and any kind of progressive moving is generally squashed by the “God and Guns” mentality that still governs Sunday lunch conversation and Little League practice idling.

Life outside that culture—life as an artist (for instance) in the South—can cause you to question your own sanity over and over and over again—daily, hourly even. Had it been my grandmother’s South, I would have been sealed away in an asylum by now or strung up by a lynch mob.

I can feel the tightening of the rope-knot around my voice and around my spirit in a kind of nightmare reality even as I write about things of the free soul.

The irony is that the very same man-preacher who cracked the washing machine joke is the man who encouraged me, White Woman, to travel to Southern India as an evangelical missionary because I sincerely believe he saw in me a very practical capability that went far beyond gender constructs.

India, of all places.

Had I not known him better, I would have thought it was a sure-fire way to be rid of me and my uncomfortable questions for good.

In the initial meeting in an Indian hell-hot, tin-shed worship service that felt very much like a Mississippi July, the pastor introduced me in front of the church, waited until I clambered clumsily from the floor, double checking that the scarf over my head was in place, and then he handed me the microphone and sat down. I stood there, dry-mouthed and wide-eyed, struck with a thought that hit me hard in the gut all at once, one that in coming years I would shove down against the pangs of threatening insanity again and again, and that was that I realized in that moment with shocking intensity that I had just been treated with more respect by the Middle-Eastern church than by my own Southern Baptist church.

That one gesture of respect in itself was enough to rewrite my pain, though. It was enough to cause me to question the deep waters of my own spirituality for the first time and peek out from behind myself with new eyes, curious about what we really mean when we say things like “God” and “Soul.”

Did I really recognize my own soul or was I only a product of inherited ideology?

What if I had gotten it wrong?

What if I had been blinded by teachings of difference when the key was a recognition of sameness?

As the subtle workings of synchronicity would have it, I met both difference and sameness in a woman in a dress shop two days later.

The second encounter that caused me to stop dead beneath a sun-scorched sky and look at spirituality in an alternate light was with a woman named Lucky who wound tapestries of history about me to the beat of dohl drums in temple hollows.

An older Indian woman and a young American woman bound by the same foreign ropes of domination, mirroring similar souls bred from the social-soil of two different continents.

In the midst of her fussing and pinning sari cloth and moving like a locksmith about my body, I was both woman and child and the world was all at once completely virginal and completely sadistic. In her mother eyes, I saw a mysterious darkness, ashes left from years of subjugation, but there were islands in her eyes, too, and a kind of peace that rolled in and out like Arabian tides at mid-day when the light off the water is both intricately lovely and sharply blinding, a kind of stained-glass stunning of the soul.

Hatred is as illogical as love. She knew that just as I did. I could tell by the wrinkles about her eyes.

And in a way that words refuse to encompass, that was a strong astringent on a wound that, in that moment, began to heal.

It was not until I had been all the way around the world and back again, several times, that I began to understand the layered complexity of religious prejudice.

Prejudice is the black-dog guardian of our own fears.

Take away prejudice of any kind, religious, racial, or sexual, and all one is left with is one’s own soul questions, naked and trembling before the light of divinity.

The preacher who insinuated that women are for babies and chores is the same man who encouraged me to go into Muslim Africa. He also watched me set up a ministry in the inner-city of Jackson, Mississippi where I learned life and hunger and a special kind of starving for stories. Stories that would scandalize any neat, clean, Sunday morning suburbanite, sending them to their knees with grief over the world in which we are forced to exist.

Not because they do not also know that same grief, but because it is told with as much brutal reflection as that sunlight off a foreign sea.

These stories were of pain and rage and victimization, same stories as church people, just unflinchingly honest, with nothing to hide for reputation’s sake. Stories of gangs and needles and rape, drugs and guns and homelessness, and poverty and despair so deep that many of us would recognize it instantly.

Agony: Mine. Ours.

Pain is communal. If we learn that, we un-learn prejudice.

So what was the Southern Baptist Church so afraid of?

A little white girl? Yes. Me. And of women like me who are representative of a greater population of repression.

Bold women who are not content with babies and bake sales and basements of churches. Women with sh*t to say.

Women who will gladly don saris and lower their eyes in countries that hate them (America the same as India) for the sake of a greater message—women who refuse to swallow the forced message of unrequited submission, spitting it out like a lukewarm revelation onto a ground soaked with the blood of martyrs.

Overall, preachers like the one who entrusted me to ministry on three separate continents, but not the podium of my own church, are not malicious.

The majority of them are not out with the explicit purpose to keep women or minorities down.

They are facing the same difficulties as everyone else is, their words just have a longer arm.

Anyone who holds to doctrines of inequality or prejudice is afraid of what we are all afraid of on some level: being exposed as answer-less, having to look head-long at our own stories, and therefore our own souls.

That Sunday, as the preacher whom I both deeply admired and deeply resented, told his joke, my body all at once knew the ambiguity of contradiction, the soul struggle that defied age, race, or gender.

I rose, trembling, as dozens of heads turned.

I swallowed, swallowed, swallowed down the light that kept forcing its way up the back of my throat as a reminder of my own physicality—I am Soul hindered with Body.

And then I walked the aisle again, this time toward the exit instead of the altar.

Indian-beaded skirt hem skimming the Baptist-burgundy carpet, Moroccan bracelets clanging on both arms, head down to hide hot tears, mantra running on record in my head to the rhythm of my feet, “Don’t cry, Meg, don’t cry, don’t cry, dammit don’t cry, Meg.”

And then as the hard sun hit my face on the other side, I sucked in air so violently that I choked and vomited in the Saturday work-day shrubs, wiping my mouth with the back of my hand as the morning light cut jagged across the street, haloing the concrete dead in a cemetery of lives that had not the strength to roll back their own stones.

For a micro-second in the universe, I, Woman, Married, I, a once youth pastor, overseas missionary to India, Africa and Europe, Evangelical Christian zealot, willing lamb, I…

Stood alone in front of a church that had betrayed me, or a church that I had betrayed, wiping vomit from my mouth, caught at Robert Frost’s proverbial crossroads, alone yet again—Jezebel of the South.

Three years, one scarlet letter, and thousands of whispered prayers later, I sit alone again, in my own soul-space this time, in a night lit by candles and bright bulbs, settled in a silhouette dark beneath a moon that makes me ask of God and I am thankful for wrong doctrines that taught me how to ask right questions of myself.

The only sermon that was ever worth preaching, that terrible Fall and the universal destinies mankind inherited as a result, taught me this: we are all the same soul, stretched thin by pain and wear, but triumphing in our own unique ways every single day as we wade our mud-drenched paths through the waters of this world.

That alone should tell us something.

Tits may not preach in the South yet, no “other kind” of body or race, but a message that renounces hate and prejudice in the name of solidarity.

That, my friends, is a message that will preach anywhere people are bold enough to admit that souls feel way more honest than bodies.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Apprentice Editor: Jess Sheppard / Editor: Renée Picard

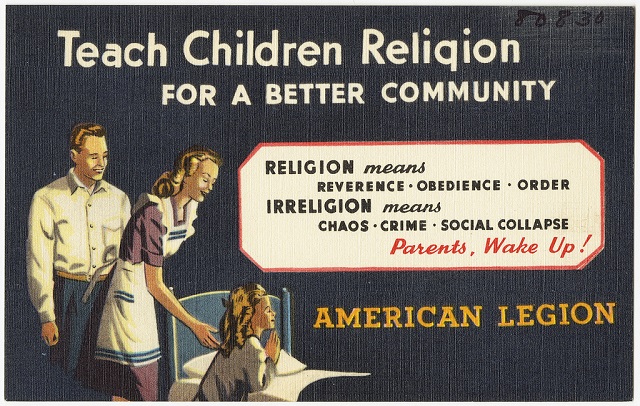

Image: Flickr

Read 5 comments and reply