Meditations on healing and integrating the shadow:

I want to talk about capacities today—those capacities we are being asked to develop in order to face the complexities and problems that are plaguing our communities. We’ve inherited chronic and sick systems, which simply aren’t working anymore. We can either play the victim, or rise up to face what we ourselves have been partially responsible in creating.

There’s a compelling need for deep courage, resilience, vulnerability and compassion. There’s an even greater need for innovation and systems thinking.

But before getting overwhelmed by all that’s wrong with our collective communities and systems, let’s dial it down a little and come back to ourselves. It’s imperative we face our own shadows and deal with our individual biases and patterns that hold us back. Without developing self-awareness on how we show up in the world, we’re going to keep making the same mistakes, projecting our own suffering outside of ourselves, and ever-conveniently blaming the “other” for all that’s wrong around us. Responsibility and action become simpler to avoid when we don’t claim all parts of our self.

This past Friday, I spent my time in Old Dhaka experiencing a public art project called “1mile²” organized by Britto Arts Trust (stay with me, I promise this is related to the above).

This art walk in itself was a phenomenal multi-layered collaboration to connect the intersection between culture and the environment within diverse societies. The opportunity to experience participatory arts across different social groups and platforms left ineffable impact so I’m going to choose to focus on only one installment by Ayesha Sultana called “Rupture.”

Ayesha chose to work on a feature wall in one of the locations of 1mile² called Panch Bari. Panch Bari is an old residential structure that is owned by five brothers (thus the name).

Very little remains of the original architecture, but there still stands a courtyard of sorts surrounded by dramatic pillars, arches and beautifully detailed walls. The top layers of the walls and arches have peeled away, leaving behind and exposing brick and mud innards, pierced by juts of knotted plants and seemingly ancient roots.

I immediately fell in love with the nostalgic and decrepit feel of the place and when Ayesha told me this part of the house was used for the Hindu family’s rituals, my imagination needed no further coaxing to run wild. This place was already magic to me, and the simplicity and depth of Ayesha’s work did me in.

As you can tell from the picture above, there’s little she’s perceptibly done but in actuality, there’s layers of detail, intention and thought behind the work. She intricately gilded the deep running cracks and nooks with actual gold. It was a stunning and contemplative choice.

She could have just as well taken the easy route and gilded the obvious features which were meant to stand out: the pillar heads, the designs and the arches. But her intention was not to highlight the facade and make it more ornamental.

She chose to focus on that which we tend to abhor and cover up — the cracks and fault lines.

Her choice directs my attention on to all that which we turn our backs on—these beautiful crumbling structures, this thriving community, our history. These thoughts bring up fleeting instances of discomfort, guilt and fear — all of which is better left buried, ignored and unexamined as well.

Ayesha shared how, during the process, she noticed the cracks flowed in riverine and organic patterns. As we stood some couple of hundred feet away from a choking and dying Buriganga, I couldn’t help draw an obvious yet poignant parallel: we’re slowly destroying our inheritance through apathy, greed and a myopic lens.

Ayesha’s work was obviously time-consuming, almost a meditative process because of the intricacy and finesse. As a viewer of “Rupture” I found it subtle in its unveiling, yet deeply thought provoking and impactful—basically very Ayesha (I know her well so am allowed to draw parallels.)

“It is okay to be broken, to allow yourself to fall apart

You need not hold it together any longer for you were never together to begin with

Fall apart and resist the temptation to put yourself back together again

See what is forever untouched by the concepts “together” and “apart”

It is okay to be broken, for it is through the cracks in you that light can pour through.”

~ Jeff Foster

Owning our wounds and claiming space in the world is a powerful choice.

Often, it may seem easier, and even encouraged to hide our pain under the weight of shame and fear. Gilding it with real gold and then having the audacity to display it for the world to see seems borderline psychotic, selfish and proud at the very least.

The ego insists that the cracks and wounds need to be smoothed over with cement and painted a deflective color—maybe a shiny robin’s egg blue? Maybe we can almost forget that they’re even there—those disconcerting and repulsive cracks. Even better, let’s tear down the wall and rebuild a new one…then it’s like they never even existed.

But that’s not the way life works, or more specifically, it’s definitely not the way our psyche heals. Healing takes deep and difficult work; healing requires you to look into those ugly festering cracks and owning them, even accepting them as a part of the whole entity that makes up “you.”

Owning your story, taking up and claiming space, and radiating all of who you are takes great courage and vulnerability. You’ve got to wear the battle wounds unabashedly and without an ounce of shame; even gild them with real gold if you must.

The Japanese art of Kintsugi is an ancient method for repairing broken ceramics with a special lacquer mixed with gold, silver or platinum. The philosophy behind this symbolic technique is to highlight (rather than hide) the damage by filling the cracks with gold. It speaks to breakage and repair becoming part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise and be ashamed of.

The intrinsic value doesn’t lessen because of the “broken-ness,” but actually appreciates and becomes more beautiful. The underlying Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi behind the Kintsugi technique permeates the culture and creates space for allowance and acceptance—capacities which are grossly undervalued in a culture obsessed with perfection and busyness.

This act of embracing the flawed or the imperfect is a freeing and integral learning experience, something wisdom traditions have imparted in their teachings for generations.

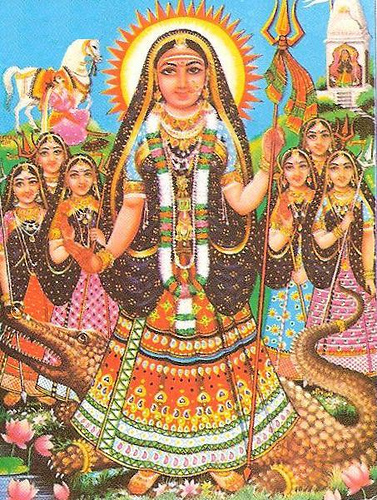

Another symbolic archetype that Ayesha’s work reminds me of is that of the Hindu Goddess Akhilandeshvari, whose name loosely translates to the “never-not-broken Goddess.”

Akhilandeshvari teaches us that when you we at our most vulnerable and wounded , when we’re a broken heap splayed on the floor, consumed with grief — in that moment, we are more powerful than we have ever been.

I’m talking real rock-bottom brokenness…the kind of broken that tears you apart at the seams and floods through all the blocks and toxic muck that can get stuck and calcified within. The kind of broken that shatters through old defensive patterns, routines and facades and pierces through the stagnation of a numbed out, auto-pilot way of being.

Embracing your broken-ness in that moment and claiming it as a natural process and cycle of being alive can be utterly transformative. Again, wearing it as though it is the most vulnerable, precious and valuable treasure within you. Holding it with love and tenderness — like it’s gilded in gold — is a bold and critical choice.

If you’re willing to do the work, really go within and look at your own shadow and claim it as part of yourself — that’s the real path to healing.

Like Robert Frost said, “The best way out is always through.” You can’t expect fragmented parts of yourself to heal, without facing them and doing the work. Get to know the broken bits within, which you work so tediously to mask. Be in conversation with those fragments in the shadow, and something alchemical and strangely beautiful may arise. Maybe you’ll strike gold amidst the depths of the ruptures.

Ayesha Sultana’s exhibit “Rupture” inspired me to write this piece because this theme of integrating our shadows has been very alive for me in my work and life in Dhaka.

Before we jump in to “help” the world, we need to do the difficult healing work ourselves. The ruptured, fragmented and desperate world around us is a reflection of what’s going on within.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Author: Ashna Chowdhury

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Photo: Author’s Own, Wikipedia

Read 8 comments and reply