One of my favorite dishes to make in winter is polenta.

It’s hearty and warm and heats the inner fires. I found a great local source from Aspen Moon Farms in Hygiene, Colorado called, Organic Biodynamic Red “Floriani” Cornmeal. It has a rich yellow color with red flecks inside. It’s open-pollinated, non-GMO and heirloom…out of Italy, which is why it is also great for making polenta, not just cornbread.

For those who may or may not know, the Italians use “flint”corn for their polenta, which I recently learned is the same as native American calico corn, which surprised me. Each kernel has a hard outer layer to protect the soft endosperm, it is likened to being hard as flint; hence the name.

Here we have an Italian variety, named Floriani, for something that was originally ours, grown by the Pawnee Indians a 1000 years ago. This tells me that the Italians were better at appreciating a rustic, heirloom variety and keeping their tradition alive, especially in the popular Alpine polenta eating mountains in the north, more than we Americans were.

This is to say that polenta, with a drizzle of extra virgin olive oil and Parmigiano-Reggiano, make a delectable ménage à trois. The addition of cavolo nero, an Italian version of flat-leafed kale, and chunks of deep orange Hokkaido or Kabocha squash, makes this dish a winter winner.

Up until about five years ago, cavolo nero (black cabbage, dinosaur kale) was not grown out of Tuscany, where it graced almost every garden in the countryside. It was mostly used for Ribbollita, the Tuscan vegetable bread soup, or fetunta, toasted bread rubbed with garlic with a mess of cooked cavolo nero on top, drizzled with pot liquor and extra virgin olive oil. It still graces Tuscan gardens, but now, all across America as well. It’s tall stalk and sky reaching leaves look more like a brussels sprout plant or tobacco. Like most hearty winter greens, it needs a frost to sweeten the bitter flavor. Yet, sautéed with garlic and olive oil, cavolo nero is a dandy dressed up peasant.

Hokkaido or kabucha is a naturally sweet, orange fleshed winter pumpkin from the Hokkaido prefecture of Japan. What sets it apart from other pumpkins is its sweet, satisfying nutty taste and texture, especially when baked or made into a pureed soup. Our American orange pumpkins are not naturally sweet and take a lot of sugar to be so. Hence, we eat pumpkin pie and rarely eat it in a savory dish.

Here is the recipe in three parts:

Polenta

1 cup of course cornmeal, preferably a variety best used for polenta

4 to 8 cups of salted boiling water

butter or olive oil to flavor (this can be corrected to taste at the end of the dish as well)

1/2 cup of grated Parmigiano-Reggiano + more for garnishing the top

salt to taste (but at least 1/4 tsp to start)

Add cornmeal to the simmering water with a whisk so it doesn’t clump. Keep stirring intermittently for at least half an hour. Add more water if necessary to keep it moist and still able to stir. It will be thick. Make sure it doesn’t pop out on you. Stir with a long spoon. It needs to cook a long time to be most delicious. Keep letting it simmer if you aren’t sure. Some people let it cook slowly for an hour. Don’t be surprised if it forms a film on the bottom of the pot. Don’t worry, this is good. It will soak out later and this keeps the polenta from burning. Check for salt. When it’s cooked to the desired consistency, able to keep your wooden spoon almost standing up, add more olive oil (or butter to taste) and a grated Parmigiano-Reggiano. Dish into bowls as is, with a drizzle of extra virgin olive oil and a sprinkle or two of good Parmigiano-Reggiano. This ménage à trois is enough as it is…or add sautéed cavolo nero and squash.

Sauteed Cavolo Nero

1 bunch dinosaur kale (cavolo nero), chopped coarsely

3 cloves of garlic, chopped

1/2 dry red pepper, chopped

extra virgin olive oil

Clean the greens and separate the leaves from the stems. Chop course and set aside for a moment. Add extra virgin olive oil, garlic and pepper. Put the greens in straightaway and sauté. Add a pinch of salt and cover for five to 10 minutes, stirring occasionally. Cook to your desired tenderness.

Braised Hokkaido pumpkin

1 half of a pumpkin

2 shallots, sliced fine

Cut the green skin away from the flesh of the pumpkin. Remove the seeds. Chop into bite sized cubes. Sauté shallots in extra virgin olive oil and add the cubed pumpkin to sauté together. Add a little water to braise. Stir often checking for a small amount of saucy liquid. Salt to taste.

Add greens and squash to a bowl of polenta, sprinkled with grated Parmigiano-Reggiano and a drizzle of your best extra virgin olive oil.

~

Read on if you would like to know more about my philosophy of food and how Parmigiano-Reggiano is made.

We can learn the ways of the old ones by going back to how they ate before the Industrial Revolution, back when there was integrity, family and story involved in producing an artisan product by hand. With the help of Slow Food and other movements, there is a global resurgence to grow locally and create the artisan story as well. It’s nothing new and yet, it is. We have not been taught to eat what grows around us in season and preserve for the cooler months. Or if we have, we choose not too. We don’t have time perhaps, but worse still, is that we have little relationship to what grows in season or the absolute heightened taste that comes with it. We are used to picking anything up at the grocery store that we need. Acidic pineapple. Tomatoes that taste like mush. Puckering mangos.

We (most Americans) feel entitled to have what we want at all times, without thinking of the implications. We may be spoiled, but if you think about, we are not. We are just missing out.

There is an Italian cook book from 1891 called, “La Scienza in cucina e l’Arte di mangiar bene.” Science in the kitchen and the Art of eating well by Pellegrino Artusi. Artusi was a Florentine silk merchant, a gastronome, a bon vivant, a noted raconteur and a celebrated host, who knew many of the leading figures of his day and read widely in the arts and sciences. What this book offers is a way of life. That food, how we prepare it and how we feed ourselves, should not be separate from how we live. If we care about cultivating our minds in an intelligent, mindful and artful way, why not how we eat?

After all, the best conversations are born at the table, whether you are happy or sad, having a good cup of tea, a simple meal or a banquet. Whether you are with one or several, or even alone, you can appreciate the finer nuances of life in the simplest hearty bowl of soup or polenta with olive oil and grated Parmigiano-Reggiano. You can appreciate the color of the corn, contemplate how it was ground, who grew it and in what region. A drizzle of spicy, peppery olive oil reminds us of the care the contadini who looked after the trees, harvested the olives in cold November and waited hours at the frantoio. Sometimes they wait through the night. The machines never stop during harvest. They must watch to make sure their olives don’t end up as someone else’s oil. They hold court for their freshly picked fruit to pass through the press and flow out bright green, pungent and full of antioxidants. Extra virgin olive oil. Our hero. A compliment to any dish. Even ice cream.

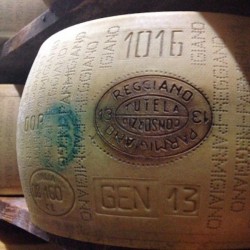

You might wonder about the complexity of Parmigiano-Reggiano and why they call it the king of cheeses, probably not knowing that a wheel is actually born and that the process of aging is controlled by an expert grader from the Consortium that tests each wheel with a small hammer to make sure it’s worthy of the stamp of approval. Read here for the full disclosure of how the King is born.

I have experienced it myself in Pavullo, on cold dark mornings at six a.m. First comes the milk from the black and white cows, which we have said good morning to, then the process begins in deep copper vats. It’s quite a process of steps and by eight a.m., the curds have separated from the whey and collected at the bottom of the vat. The cheese maker midwife, takes a long wooden paddle and slides it underneath the form at the bottom and with a lot of strength, uplifts and “births” about a 200 pound cheese that gets separated into two rounds (as it they were twins) and are hung in muslin and strapped to a poll to drip until it’s pressed into a stainless steel, round form that is pulled tight with a spring-powered buckle so the cheese retains its wheel shape.

After a day or two, the buckle is released and a plastic belt imprinted numerous times with the Parmigiano-Reggiano name, the plant’s number, and month and year of production is put around the cheese and the metal form is buckled tight again. The imprints take hold on the rind of the cheese in about a day and the wheel is then put into a brine bath to absorb salt for 20 to 25 days.

After brining, the wheels are then transferred to the aging rooms in the plant for 12 months. Each cheese is placed on wooden shelves that can be 24 cheeses high by 90 cheeses long or about 4,000 total wheels per aisle. Each cheese and the shelf underneath it is then cleaned manually or robotically every seven days. The cheese is also turned at this time.

At 12 months, the Consorzio Parmigiano-Reggiano inspects every wheel. The cheese is tested by a master grader who taps each wheel to identify undesirable cracks and voids within the wheel. Wheels that pass the test are then heat branded on the rind with the Consorzio’s logo. Those that do not pass the test used to have their rinds marked with lines or crosses all the way around to inform consumers that they are not getting top-quality Parmigiano-Reggiano; more recent practices simply have these lesser rinds stripped of all markings. This is just the making of the king of the cheeses that is grated on your favorite dish, not to mention the life of the farmer and his wife and children who can never leave the farm or miss a morning.

Enjoy this delicious one dish meal!

~

Author: Peggy Markel

Editor: Rachel Nussbaum

Photo: Peggy Markel

Read 1 comment and reply