“Compassion and altruism are the key to low inflammation and even a longer life.”

That’s a line I saw on a website the other day.

But this wasn’t some cheesy self-help website. This was the personal website of a prominent researcher of meditation and compassion who has three Ivy League degrees and a prestigious title at Stanford University.

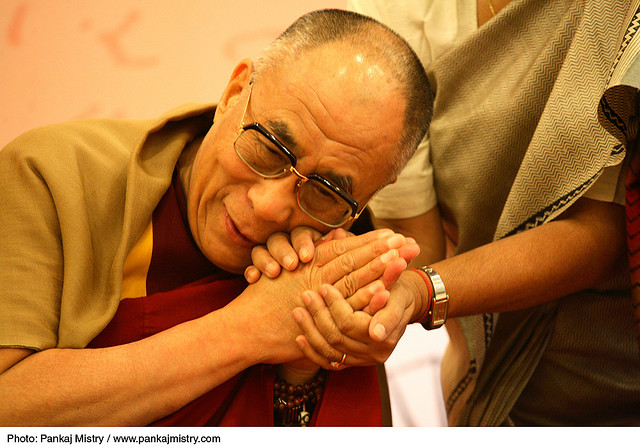

This person has helped promote the benefits of meditation. She speaks five languages and has encouraged such diverse populations as college students and active military to take up a spiritual practice. Her about page shows pictures of her with the Dalai Lama, Eckhart Tolle, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, and Thich Nhat Hanh.

I’m not going to name names here because it’s not about this individual, who clearly is smarter than me and probably a better person too.

What I want to talk about is this way of advertising good things. We do this all the time whenever we say “meditation reduces stress,” “yoga is good for your health,” or “people who go to church are happier.”

What I want is to have a discussion not about the ethics of marketing, but about the marketing of ethics.

Here’s a ridiculous hypothetical example for you:

What if science were to discover that strangling puppies and drinking their blood was more effective than compassion and altruism at reducing inflammation and increasing lifespan?

Should we therefore engage in puppy vampirism instead of practicing compassion and altruism?

Obviously not. Only a psychopath would advocate for such a thing.

But why not? Why would it be wrong?

It would be wrong because of the harm caused to the animals, which is to say the needless pain and suffering inflicted on other beings. Yes, there would be a benefit to the health of the human recipient, but the cost would be too great.

But in order to reason this way at all, we have to consider that other beings are worthy of our moral consideration.

We non-psychopaths believe that other beings actually exist, that they suffer, and that their suffering should be considered when doing things that benefit us.

Hey wait, we just accidentally backed ourselves into altruism and compassion!

How did that happen?

It must be that we believe we should not seek to benefit ourselves at the cost of altruism and compassion. By saying this, we are recognizing that we already believe altruism and compassion are not simply means to an end.

In this single line, “Compassion and altruism are the key to low inflammation and even a longer life,” the presupposition is that compassion and altruism are a means. The end is health and longevity. If we could find better means to accomplish these good ends, we ought to do so, in order to maximize the good we can do with our lives.

In other words, this little, innocent sounding marketing pitch assumes that the only good is what is good for me—an ethical view called Egoism.

But this cannot be the case, because altruism and compassion are ends, not means, as we’ve already established. We are unwilling to sacrifice these good ends for personal gain, such as a longer life or less inflammation.

If we can get a longer life or better health, those would certainly be good things, but if we have to sacrifice other goods like the well-being of others, we ought not to do it.

In fact, we might even argue a case for sacrificing health and longevity to attain virtues like compassion and altruism!

Imagine someone who lives a long and healthy life, but periodically strangles puppies and drinks their blood for the health benefits. Is this a good person who is living well?

Now imagine someone who suffers from an inflammatory disease that will likely cut their life short, but they refuse the puppy strangling treatment on moral grounds, dedicating their short life to caring for others.

Clearly a long, healthy, but selfish life of sacrificing compassion and altruism is not a good one, whereas a short life of compassion and altruism can be downright heroic.

So here’s the thing: we ought to stop encouraging people to do good things by framing them solely in terms of self-interested motives.

Doing so erodes the basis for actually doing good. It reinforces a society of corrupted values where what is good for me is seen as the only good, a society of Egoists selfishly pursuing their own interests regardless of the harm it does to others.

And look around—that’s the society we currently live in, a society that things like meditation, compassion and altruism presumably could change if they were more widespread. And that’s precisely why compassion and altruism are important to encourage.

But ours is a society where our values are so corrupted that we cannot even conceive of telling people they ought to do good in terms of anything except “what’s in it for me.”

Framing ethics in terms of self-interest backfires, as Barry Schwartz and Kenneth Sharpe discuss in their excellent book Practical Wisdom. (A summary can be grasped in Schwartz’s TED talk here. It leads people to frame things in terms of self-interest. As a result of this framing, people stop doing good things if they don’t maximally benefit themselves, even though they also value doing good for its own sake.

Selfish framing highlights our personal desires for things that benefit us alone, overpowering our more selfless values.

If compassion and altruism are good, shouldn’t we engage in these things for their own sake, not merely as means to an end? Indeed we should.

Instead of saying “compassion and altruism are the key to low inflammation and a longer life,” we ought to encourage people to become more compassionate and altruistic because these things are good in themselves, not as means to another, actually good end.

Of course then we wouldn’t need research on the health benefits of being kind to others, because kindness would not be lacking justification. Altruism only lacks justification when we assume people only have selfish motives, a horribly cynical view of human beings which denies our very humanity and what is of ultimate value to us.

By framing non-egoic ends in terms of egoism, we are bizarrely contradicting ourselves. And do we really think we can convince hardened Egoists to be more altruistic by appealing to self-interest?

It seems to me that people seeking to be more compassionate and altruistic are probably not Egoists, but already subscribe to an ethic that includes the well-being of others as valuable. Otherwise they would readily assent to puppy-strangling vampirism as a longevity tonic.

Given that these people already agree that compassion and altruism are good, why appeal to Egoism? Instead, we ought to draw out the compassion that is already there by encouraging people to be compassionate because being compassionate is the right thing to do.

Bizarrely, people are more comfortable in our society claiming that the good they do is for their own benefit than admitting the truth—that they actually care about others and want to live a good and noble life.

Peter Singer notes this in his book The Life You Can Save when he talks about individuals who live incredibly selfless lives. One man, when asked why he does his heroic deeds says that’s it’s just “how he gets his kicks,” as if his heroism is morally equivalent to watching television, just something he does for entertainment. But his sacrifices clearly indicate that this is not true: this man’s motivations for helping others ceaselessly cannot possibly be primarily for his own benefit.

The truth is, it is uncool to care.

It is so uncool to care that people who have dedicated their lives to caring for others will actually lie about their selfless motives, as if to protect themselves from being nailed to a cross if word got out. Selfish motives on the other hand are 100% socially acceptable.

We ought to become more compassionate and altruistic not for the personal good it does for our health, but for the benefits it has for others. The fact that it also may have some benefits for me personally is a nice side-effect, but not the reason for doing it.

If we presuppose that the reason for doing good is to personally benefit, we not only don’t convince any puppy-murdering psychopaths or merely selfish Egoists to care about others, but we also contribute to a degraded society of selfishness and moral decay, where moral relativism rules and nothing can be said to be good or bad (except telling people that some things are good and others are bad—that is a no no).

Only by encouraging people to do the right thing for the right reasons can we move things in the direction of a more enlightened society. But sadly, few are willing to take this heroic stand against the tide of selfishness, even amongst those who have dedicated their lives to compassion, altruism and other virtues.

Relephant:

How Meditation Makes You Healthier According to Science.

Author: Duff McDuffee

Editor: Travis May

Image: Flickr/abhikrama

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 11 comments and reply