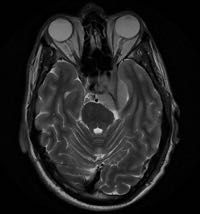

I had really hoped to avoid brain surgery in my life—but recently, I was diagnosed with a treatable, operable tumor quite literally in the center of my head.

The two things that helped me handle my diagnosis were my training in yoga philosophy and practice and more than a decade of counseling. At this point in my life, I know my triggers and pretty much everything that scares me. I know how surgeries and invasive, often impersonal, medical interventions affect me. I had no hesitation acknowledging the range of my feelings and admitting to friends that brain surgery terrified me. “As it would anyone,” said a friend.

But, from what I understand, I don’t need to experience any pre-operative pain to show up for my surgery—another MRI and a couple of IVs is all. My preparation thus far seems primarily psychological.

Recently, I’ve had extended periods of not feeling afraid. I’ve even begun to reflect on the idea that I can welcome surgery. It’s going to help me heal and perhaps shift my path back towards my pre-diagnosis normal. But even while I feel confident and relaxed, there’s a voice in my head telling me I’m supposed to be afraid.

Basically we’re afraid of everything in America: immigrants, minorities, gays—pretty much anyone that’s different than us. We’re afraid of things that have little mathematical risk (like terrorism) and less afraid of things that do (like heart disease).

I think the voice in my head is the echo of our culture of fear.

Why else then when faced with brain surgery is the default to be terrified rather than confident in my highly trained neurosurgeon. Why am I not so inclined to be grateful for the teams of supportive, caring professionals that will watch over me?

Fortunately, I have some familiarity with this subject.

Surgeries Past

I had a major hip surgery as a toddler; I don’t remember any of it. At age five, I had a tonsillectomy. A nurse came in beforehand to ask me where I wanted my shot. I pointed to my penis, and then in response to her annoyed frown, clarified that I meant the opening of my urethra—the one place a needle wouldn’t hurt. Frankly, this may be the earliest example of my creative genius. She jabbed me in the butt. The last thing I remember was lying on an operating table with a handful of adults in green scrubs hovering over me, like in The X-Files, as one asked me to take a few breaths into a mask.

The irony of the fact that I’ll finally be catheterized during my brain surgery is not lost on me.

Since then, I have had quite the range of surgery experiences. I’ve canceled dental surgery due to the fear of being “put to sleep”. I’ve undergone hypnosis to help me prepare for shoulder surgery; the suddenness of waking from general anesthesia arrives with a sense of lost time. My yoga training made a recent knee surgery feel much more manageable, though when the surgeon asked me how I was doing, I told him I was nervous. “You wouldn’t be human if you weren’t,” he replied. It was more reassuring than I expected when he initialed the correct knee.

Facing Fear

By and large, all of these past surgeries were very good to me—but brain surgery feels different. The opening of the skull, which clearly evolved not to be opened, exposes the center of our thoughts and our consciousness. The risks are higher as well. The possibility of stroke, disability and death feel, well, larger than life.

So I do have moments of dread at what’s to come—usually when I wake up in the morning.

Here are my main concerns: How will I be able to give up my last pre-surgery moments to go to sleep the night before? What will it be like to ride to the surgical center, sign the final forms, change into scrubs and sit through the pre-operative preparations?

In “My Summer Brain Tumor,” Rebecca Kurson (who had a similar tumor to mine) describes this period: “My husband takes me to the hospital at 5:30 a.m. and within an hour I am alone and being prepped for surgery. As they put me under anesthesia, I lose control altogether and scream, ‘I am so scared!‘ It is the last thing I will hear with my left ear.” Reading this made me viscerally uncomfortable; it shook my confidence and left me overwhelmed at the prospect of handling that level of fear.

A yoga teacher of mine whose husband has had many surgeries said that even our primal survival instincts react in these moments.

My friend Jeff Harris basically had to be cut in half for his 17-hour surgery. At the time, I wondered how he could face it. Now I understand a bit about this: the alternative to surgery sucks worse. It turns out that the answer to how people rise to the challenge of these kinds of surgeries is that they are the best—or only—choice.

People say that I’m brave. I’ll own a bit of this, but frankly not having surgery would be much scarier. Both Kurson and Harris knew they would lose significant functionality in their surgery. I only will if there are complications, which I’ve been told are unlikely.

For many years, I’ve been afraid of heights yet fascinated by movies about climbers and extreme sports. A couple of great mountain scrambling instructors took me under their wing a few years ago and taught me that to manage my fear, I needed to focus solely on the next step in front of me. With this simple guidance, I reached a summit I’d turned back from weeks earlier.

Similarly, when I feel dread for the upcoming surgery, I recognize that there’s nothing to be gained by dwelling on the fear of the future right now.

Staying Present

In yoga, this is called staying in the present moment. It’s reassuring when diverse disciplines like yoga and climbing reveal the same fundamental instruction.

As I wrote earlier, focusing on the breath in yoga is the first step to calming the mind. Someone recently told me, “You can think about the past or the future but you can only breathe in the present.”

A friend compared my journey toward surgery to managing the challenge of a difficult yoga pose. Her teacher once asked, “What would you need to adjust in this pose to stay in it for 100 years?” Staying relaxed and confident as I navigate my diagnosis and pre-operative planning is very much like the practice of finding the appropriate balance of effort and quiet in a difficult pose.

Laughing helps. A friend suggested we make a list of the qualities I should ask my surgeon to keep safe (my excellent parallel parking skills) and those she should remove (always choosing the slowest line in the grocery store).

Gratitude is important too. Last year I traveled to India—an experiential gift of being in a culture that prioritizes living in the moment. In Varanasi, our group had to press to the sides of a narrow alley to allow room for mourners carrying delicately draped bodies high on stretchers for cremation. Beside me, my yoga teacher said, “Be thankful for the gift of your life this moment.”

We also spent time at an orphanage in Tiruvannamalai with children who are HIV-positive; “Tiru” is a spiritual center beside Arunachala, the mountain where yogi Ramana Maharshi lived after experiencing enlightenment at age 16. The children immediately latched on to my camera to take pictures of each other, thrilled just to take photos and have visitors. It was difficult to leave them and heartbreaking when they asked us when we would return.

The truth is that I’m tremendously fortunate to have lived a life of relative privilege and security. I’m grateful that my brain tumor is operable and treatable, that I’m insured and don’t have to worry about money on top of everything else. I’m appreciative of modern medicine, that there are teams of people who work every day to provide great care and a neurosurgeon who enjoys holding people’s lives in her hands and fixing their brains. This experience has highlighted for me what gifts our lives and our health are.

A big part of this process for me is the willingness to surrender: to discomfort, to some amount of pain and to the acceptance that my health afterward may differ from what it’s been until now.

Directing Focus

Through yoga, I’ve trained to sit with my feelings and invite in the full range of my emotions. I’ve become familiar and confident in the refuge of a calm mind through repeated experience that begins with observing my breath. It’s spiritual for me.

But on the morning of my surgery, I may still cry. I may tremble. I may scream. If directed by the flight reflex of my lizard brain, I may run. I hope it’s someone’s job to block the door.

Ultimately, in the moments leading up to my surgery, there will be so much more than fear to focus on. There will be profound intensity, curiosity, hopefulness, gratitude, trust, eagerness, great care, an opportunity for transformation and a lot of surrender. I will focus on all of these things.

If that fails, I’m told they will give me drugs.

My friend Karissa signs her emails, “Love is what is left when you’ve let go of all the things you love.” I have come to understand that no one is promised anything in this life and I’ve been given so much more than most.

When I wake up from my deep surgical sleep (with a “headache”, I’m told) I will be so grateful for the gift of waking and for every opportunity that follows. If in the less likely scenario I don’t wake, or there are complications, I am trying to be okay with that too. For now, I’ve made reservations to return to India later this year. We’ll be visiting another orphanage and perhaps I’ll find my way back to Tiruvannamalai.

~

Author: Jeff Reifman

Editor: Alli Sarazen

Photos: Author’s Own

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply