The philosophy of Nonduality (Advaita) has gained a lot of popularity in the West.

It is a type of spirituality that scientifically-minded often feel attracted to.

If you are interested in Nondual spirituality and its goal of transcendence of our limited way of experiencing life and of ourselves, this article will give you an overview of what it’s about. If you’re already studying this form of spirituality, the last part of the article (on neo-Advaita) might help you better navigate some of the problems in the contemporary teachings.

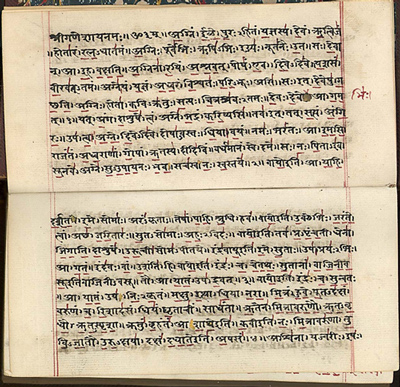

Advaita Vedanta is perhaps the oldest nondual tradition. It is based on the teachings of the Upanishads, the Brahma Sutras and the Bhagavad Gita. It’s most famous historical exponent was Adi Shankara, who in the 800 CE revived Hinduism in a Buddhism-dominated India, winning over all opponents in debate.

I’ll outline the differences between traditional, modern, and neo-Advaita. While the philosophical framework has remained basically intact all along, the approach to practice and enlightenment radically changed.

“Just as Yoga has undergone many distortions in the West, which has reduced it largely to a physical asana practice, so too Advaita is often getting reduced to an instant enlightenment fad, to another system of personal empowerment or to another type of pop psychology.” ~ David Frawley

Traditional Advaita

In a nutshell, Advaita teaches us that:

- Reality, or the Absolute (Brahman) is eternal, undifferentiated, transcendental, beginning-less Awareness, “one without a second”;

- The universe, all beings, and the creator are all manifestations of Maya (Illusion), and are “unreal” on themselves

- The universe, all beings, and the creator is Brahman (thus are real as Brahman)

- Our essential and true Self (atman) is one with Brahman.

The perception of multiplicity and of an “external” universe is compared to a dream, or to a rope that appears to be a snake in a half-dark room. Enlightenment is the realization of our true nature as Awareness, and the consequent dissolution of the illusion of being an individual identity (sometimes called “ego” or “mind”), just like a mirage ceases to deceive when it is seen to be illusory.

The path to enlightenment involves hearing/studying about the truth, contemplation on the truth, deep meditation on the truth, culminating in a state of meditative absorption (Samadhi) in which that truth is directly experienced and integrated. The truths meditated upon are the ones exposed above, often under the form of “Great Sayings”—such as “I am Brahman” and “I am That.”

Or as an exercise of denying identification with anything that is perceived, “not this, not this” (neti neti).

The main obstacles on the path are known as vasanas (or samskaras), the innate mental predispositions, conditionings, or psychological colorings. These psychic patterns are based on the illusion of individuality, and reinforce that illusion; they are at the root of all our desires, aversions, fears, and ignorance.

Advaita, then, was mostly a monastic tradition. These advanced teachings were imparted only to “worthy disciples,” which meant people that have spent at least 12 years studying with a master.

The student, to be considered mature, needed to have developed the following four conditions:

- Spiritual discernment (viveka)—to be able to tell the real from the unreal, permanent from impermanent, true from false

- Dispassion or non-attachment (vairagya)—letting go of desires and attachments to everything except Awareness

- Six virtues (shat-sampad)—tranquility, self-control, renunciation, forbearance, faith, meditation

- Intense yearning for Liberation (mumukshutva)

As you can see, the bar is set quite high, and most practitioners would not qualify. Those who did were highly mature, self-controlled, selfless, desire-less and wise individuals. So the chances of the teaching being misunderstood or misused were very low. To such advanced disciples, the teachings of Advaita Vedanta could quickly bear fruit. Until then, it was not taught, for it would be like good seed thrown in infertile ground.

The onlooker, unaware of all the previous training and preparation, might have the impression that the final teachings are magical, and if we could simply jump directly to them, then realization could be speeded up. Yet, the magic doesn’t work without all the preparation.

This model is indeed very restrictive, and can benefit only an increasingly small number of highly “spiritually mature” people.

Modern Advaita

Swami Vivekananda, in the end of 19th Century, was a key figure in a second revival of Hinduism, and in spreading its philosophies and practice to the West. He was a strong proponent of Advaita Vedanta, and that was “the principal reason for the enthusiastic reception of yoga, transcendental meditation and other forms of Indian spiritual self-improvement in the West.”

Another important figure was Sri Ramana Maharshi (1879~1950), who many considered to be the foremost Sage of 20th century India. Ramana attained full Enlightenment at the age of 16, while doing Self-Enquiry (atma vichara) only once.

The teachings, realization, and worldview that came from his Enlightenment is in accordance with those of Advaita Vedanta, even though he did not have a master in this tradition. The practice he advised, however, was different than that of traditional Advaita.

The Self is already realized; it is the only reality, already here and now. The only thing that needs to be done is to dissolve the illusion of being an individual, a separate “I”, along with all the mental conditionings (vasanas) that support the existence of this ego.

This, Ramana says, is directly achieved by:

- Self-enquiry—seeking the source or the true nature of our individual I, until it gets dissolved in the Heart, or pure Awareness (path of knowledge, jnana)

- Self-surrender—surrendering this “I” to God or the Guru, with the feeling of completely giving it up (path of devotion, bhakti)

So, instead of meditating on our identity with Brahman, or mentally rejecting identification with phenomena, the Maharshi advises us to dissolve the ego by seeking is Source, or by surrendering it.

Ramana says that only a mind that is extremely mature, introverted, and calm is able to fully dissolve in the Heart, resulting in Liberation; before this, it will simply be drawn here and there by its own tendencies. As the sage says, “Self-enquiry begins when you cling to your Self and are already off the mental movement, the thought waves.”

Even though the Self is the only reality, there is a clear instruction that spiritual practice is essential. He continuously emphasized that only a “ripe mind” will be able to easily find Liberation. For all other seekers, a long period of “drying up” through purposeful spiritual practice was needed.

The Maharshi also made clear that actions have their consequences, and one must not feel that “anything goes”, because “everything is unreal.” Despite being hard-core non-dualist, he also accepted the role of dualistic devotion to God, and gave instruction to aspirants who had this inclination.

Another difference is that the Maharshi never advised anyone to become monastics. He taught that true renunciation mental rather than physical, and advised people to follow the life natural to their condition, but without the concept that there is an “I” that performs the actions and reaps their consequences.

We can say that Swami Vivekananda and Ramana Maharshi “secularised” and “modernised” Advaita Vedanta, making it practical for seekers from different walks of life.

“Just as a piece of coal takes long to be ignited, a piece of charcoal takes a short time, and a mass of gunpowder is instantaneously ignited, so it is with grades of men coming in contact with Mahatmas.” ~ Ramana Maharshi

Ramana was a pragmatist, and put no emphasis in an intellectual understanding of spirituality. This did not prevent him, however, from recommending the study of several traditional Advaita texts, including: Yoga Vasishta, Ashtavraka Gita, Avadhuta Gita, Ribhu Gita, Advaita Bodha Deepika.

Another iconic 20th century Advaita master was Nisargadatta Maharaj (1897~1981). To a great extent, his teachings were very similar to those of Sri Ramana Maharshi, and the main spiritual practice that he advised was to hold on to the inner feeling of “I Am,” and to reject identification with body, mind, and everything that is perceived.

Some of the best books to learn more about the 20th century Advaita Vedanta of Sri Ramana Maharshi and Nisargadatta Maharaj are Be As You Are and I Am That.

Neo-Advaita

The end of the 20th century saw the rise of a new spiritual movement, inspired on the teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi (and one of his most influential disciples, Papaji) and Nisargadatta Maharaj. It has been called by many neo-advaita, pseudo-advaita, and satsang movement.

Even though these modern teachings have been inspired by those authentic sages, it is important to clarify there they are not in the lineage of any of them. Ramana, Papaji and Nisargadatta did not leave any official representatives or lineage-holders. As Papaji said, “When there is a lineage, impurity enters in the teaching.”

While neo-advaita shares with Advaita many of its theoretical teachings, the approach to practice is radically different in the former, if not totally absent. The modern “adaptation” of Advaita that happened in the 20th century got morphed into something else, and this watered-down version got greatly popularised in the West.

This brought both good and bad results.

- Good results: opened the doors of nondual spirituality for people that would not otherwise be attracted to it, serving as a platform for further inquiry. It has benefited people in abandoning certain conditioned beliefs.

- Bad results: disappointment, distortions, superficial realizations, spiritual stagnation, and even abuse of power and sex.

“Faced with both old and new misconceptions, the Advaitic student today is in a difficult position to separate a genuine approach and real guidance from the bulk of superficial or misleading teachings, however well-worded, popular or pleasant in appearance.” ~ David Frawley

The bird’s eye view of the neo-Advaita outlook is this:

- Since only the Self (Awareness) is real, and everything else is illusory, there is no need to do any spiritual practice, any learning, any growth, and, of course, any enlightenment.

- Therefore, all forms of spiritual practice, education, devotion, are simply illusions of the ego.

- All you need to do is to hear the news, drop the belief that there is something to do, something to achieve, something wrong with you, call off the search, and rest in the Self.

- “Right and wrong,” “good and bad” are all illusory concepts, so there is no expectation of ethical behavior from the teaching.

The fact that you have egotistical thoughts, emotions, and suffering does not prevent you from being the Self, because the ego is an illusion, and the Self is real.

There are many shades of neo, but this is as a generalization.

These ideas are problematic on many levels. Neo-advaita has received severe criticism from scholars and spiritual teachers, both traditional and modern, for its one-sided interpretation on the teachings and lack of practical approach.

While you may find dozens of teachings from authentic modern Advaita masters (like Ramana and Nisargadatta) that support some of the claims of neo-Advaita, there are also many other teachings that present a balanced view on this. They are usually ignored or misunderstood by many contemporary teachers who tend to focus only on the teachings that seem to promise immediate realization.

I am saying that these teachers have bad intentions. Neo-advaita doesn’t need to completely vanish—there is a place for it in the big scheme of things. My goal is to simply read the current neo-Advaita movement under the lens of traditional and modern Advaita, thus providing a map for the serious spiritual aspirant to sharpen his discernment (viveka).

In the second article in this series, I will explore the main problems with neo-Advaita, and suggest a more wholesome approach to nondual spirituality.

Points of criticism:

- Compulsory absolutization

- Rejecting spiritual practice and effort

- Consdescending view on other forms of spirituality

- Mistaking superficial realizations for full Enlightenment

- Lack of ethical framework

By sharpening our understanding as to what true Nondual Spirituality and the conditions for transformation and liberation mean, we are better equipped to navigate the sea of spiritual teachers, communities, books, and conflicting views.

Author: Giovanni Dienstmann

Editor: Renée Picard

Image: via the author

Read 4 comments and reply