I met the alleged prostitute in the courthouse broom closet.

We had a rancid mop cart between us and a bare yellowed bulb crackling over our heads, but I adopted a smile, set my files down on a box of prison-grade toilet tissue, and introduced myself.

“I’m your lawyer.”

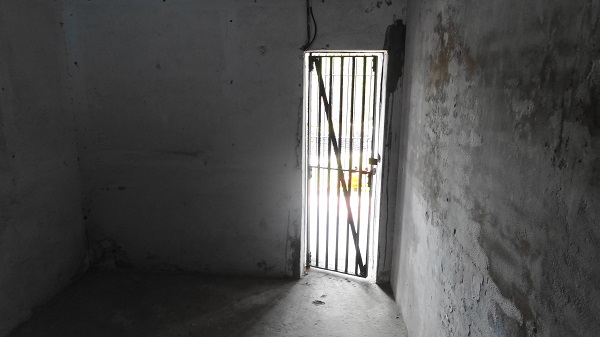

We were in hiding because she had been born he, and couldn’t pass safely through her fellow inmates; the solitary holding cell where the sheriff had stashed her had a door too thick for talking.

“I’m here to help you.”

A smirking guard turned over buckets and gestured for us to have a seat on them—which we both declined. Mocking whistles and cat-calls pierced the air, echoing from the tunnels packed with bored defendants awaiting their turn upstairs in the courtroom.

The noise was directed at my client, not me, and so the guard laughed; it was all a joke to him.

I shot him a glance that shut him down quick, then glanced over my client’s rap sheet: it wasn’t pretty. Prostitution, loitering, and drug possession had been building over the course of years.

But I kept that smile.

“Tell me your story.”*

The story was that once upon a time, there was a child who had trusted her family enough to say, “This is who I am.”

But for whatever reason, the family was unable to bear this, and cast the child out.

Nearly half of homeless LGBTQ youth report running away due to family rejection of their sexuality.

Wandering alone in raw anguish, wondering desperately of necessities, the child had accepted the first helping hand offered—thinking and judging still as a child, without an adult’s foresight or analysis.

Some experts have reported that within 48 hours of running away, one in three homeless youth will be approached by a sex trafficker.

Homeless LGBTQ kids face a significantly higher risk of sexual victimization than their straight peers (58.7 percent as opposed to 33.4 percent).

And so it had begun: an unwanted child preyed upon by strangers; trained, poisoned, traumatized by cruel keepers; and now grown-up with a collection of convictions.

Was my client a victim? A criminal?

Something in between?

The criminal justice system relied on records, but records didn’t tell the whole story here.

The system called her a prostitute; at best, an alleged prostitute. But that implied the child somehow had wanted this for herself, like it was some kind of dream which she had run off to pursue. As one advocate and former street kid explained to me, my client was more properly called a prostituted person. This saga in the justice system had begun with someone’s crime against her. It wasn’t her natural state.

My client looked ill: not peaked, exactly, but worn thin with a tiredness that threatened to swallow her.

Once a youth is recruited for commercial sexual exploitation, victims remain living an average of just seven years.

I left the broom closet determined to help my client break this tragic cycle. If I could get a treatment plan in place, maybe I could convince a judge and a prosecutor to get on board.

But the network of treatment facilities, halfway homes, and shelters which populated my rolodex proved almost useless here: finding a placement for my “special needs” client was almost impossible.

There were no residential programs devoted specifically to the unique needs of LGBTQ trafficking survivors.

In fact, in my community, many treatment centers were run by religious groups which rejected the LGBTQ identity. The prospect of my client encountering homophobia or general bullying in a non-LGBTQ-focused environment seemed high, and clearly such an experience would not help her healing.

As a technical issue, a number of programs do make beds available to LGBTQ survivors, at least in theory. Particular public grants require funded facilities to be available and safe to “all children.”

However, in practice, there just aren’t enough resources to go around. Having to compete with “more traditional” victims for placement has led to unfortunate arguments over which population has had it worse off. Competition over scarce resources has built resentment and walls between severely traumatized individuals, where there could be cooperation, coordination, and co-healing.

What happened to my client?

I did the best I could with what the world then had, and I’ve always feared that it wasn’t enough.

I am encouraged, however, by the rise of new voices to address this silent space in the community support system. The Alliance To End Slavery And Trafficking (ATEST) is a national coalition of organizations and individuals fighting to end all forms of human trafficking and slavery around the world. To that end, ATEST relies on a group of survivors-turned-advocates to inform and drive discussion of trafficking-related policy changes. They’ve taken a special interest in bridging populations and seeking out the voices of LGBTQ trafficking survivors.

This is a phenomenal first step, but the amount of work to be done is intimidating.

As a lawyer, I’d love to see an increase in shelter availability (and funding) to serve all victims as they emerge from their nightmare. But before that can happen, we need to broaden our understanding of what “trafficking victim” means.

Traditionally, the issue has been discussed as a crime against women and children, without considering other populations involved.

This is an inaccurate picture of the situation.

We also need to root out the homophobia, transphobia, or whatever-it-is which allows a suffering human soul to be viewed as nothing more than a joke, unworthy of our caring. It’s really not funny. At all.

Let’s open our eyes (and our hearts), and offer compassion to all who have been traumatized in this most horrible way.

No victim should ever be a joke, or be forced to hide in a broom closet.

*The story told is sadly applicable to many, and has been largely paraphrased here for the sake of client confidentiality.

Relephant:

10 Reasons To Decriminalize Male & Female Sex Workers.

Author: Katie-Anne Laulumets

Editor: Renée Picard

Photo via Wikipedia Commons

Read 1 comment and reply