We take so much from the world and, in comparison, give so little in return.

It is all too easy to regard even a spiritual practice with the mindset of a consumer.

With ever newer New-Age practices encouraging us to consume the universe, as though it is some kind of limitless shopping mall, we just keep taking.

Many of us approach yoga in the same way.

In my early years of yoga I practiced posture with an attitude of what can I get? In time I learned to practice asana and my attitude changed to what can I give?

Some maintain that yoga is a spiritual practice—absent from all ambition save one: to realise the true nature of self. Others claim it is possible to remove the spirituality from yoga, as one would remove caffeine from coffee, and have a fitness system ideal for the restless modern world without all that “spiritual nonsense.”

Both approaches are valid, but there is a fundamental difference: one practice explores asana and the other posture.

So what is the difference between asana and posture?

Let’s take asana first.

According Patanjali, the so-called father of yoga, asana is practiced within the context of seven other facets, making up the Eight limbs of Classical Yoga. An octagon without one side is no longer an octagon.

Asana without the other seven limbs is no longer asana, it becomes posture.

The Eightfold Path prescribed by the Buddha is similar in this regard. Take away one of the paths, Right Action for example, and it is no longer the Middle Way as the Buddha taught it.

In and of itself, an asana, the third limb of eight, is explored in steadiness and ease of the body-mind—free from tension.

In the context of the other seven limbs, an asana is sensitive, causing no pain or injury (ahimsa). It is absent of greed and vain ambition (asteya). It is generous and abundant in expression (aparigraha). It is focused, moderate and lacking egotism (brahmacharya). It is imbued with integrity and honesty (satya).

These attitudes are collectively known as yama, the first limb of Classical Yoga.

An asana is inherently satisfying, embraced and supported by contentment and equanimity (samtosa). It is passionate, fuelled by a fiery zeal to be free from illusion (tapas). It is pure in purpose, both in body and mind (saucha). It is poetic, studious, introspective and self-aware (svadhyaya). Most of all it is selfless, meaning there is no individual—that which is in division and duality (ishvara pranidhana).

These attitudes are collectively known as niyama, the second limb of Classical Yoga.

In asana the breath is organic and free from hindrance, free from all tensions and manipulation. This is pranayama, the fourth limb.

In asana the senses are not projected externally but rather withdrawn and internalised, to observe and explore the body-mind quietly, peacefully. This is pratyahara, the fifth limb.

In asana there is a single-pointed contemplation cultivating equilibrium and poise. This is dharana, the sixth limb.

In asana there is an invitation to suspend the train of thought and open the heart. This is dhyana, the seventh limb.

In asana, if that invitation is accepted by unconditional presence, then the apparent self, the ego, dissolves into the absolute reality of oneness. This is samadhi, the eighth limb.

It is hardly surprising that our busy modern minds often finds the subtleties of the eight limbs too challenging and we opt for the less sophisticated yoga posture instead.

A posture by comparison is less demanding. It can include some or exclude any or all of the eight limbs of classical yoga. It may be called yoga, just as coffee without the caffeine is still coffee, but by definition it lacks something, or perhaps some things (some limbs).

We know that the body-mind records information, stores it, and passes it on to the next generation of cells, be it within the same body-mind organism or to its genetic offspring, children.

In other words, the attitudes we practice on the yoga mat become ingrained in the body-mind and we take those attitudes off the mat and into our lives, influencing all of our relationships and interactions.

If we practice patience and generosity on the yoga mat so we become, day by day, more patient and generous. This is the process and purpose of the yamas and niyamas. If we practice vain ambition and ego driven desire on the mat so we become, day by day, more vain, ambitious and greedy.

My personal preference is coffee with the caffeine included, not excluded. Once every month or so I treat myself to a real cup of coffee, usually with some organic cookies. Oh yeah! It takes me about a month to come down from the caffeine and sugar high, but I love it. Moderation.

I like my asana the same way I like my coffee, inclusive rather than exclusive. The only difference is it’s a daily treat rather than a monthly one. Dedication. Then I remember it’s not my asana at all, it’s not even my body-mind, it all belongs to the unconditional Divine. Devotion.

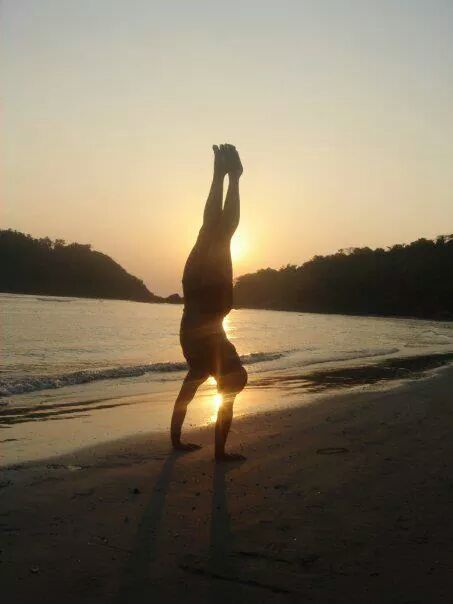

There are two ways to interpret the photograph you see with this article. The first is Arun in India practicing handstand posture. The second is, adho mukha vrksasana, there is no Arun (there is no spoon?) There is only the singular expression of the Divine, no different from the sea and the sunset that lie behind.

It’s a curious thing—as much as I used to take from yoga I was never entirely satisfied, but now that my primary motivation is to give to yoga, my heart is content.

Posture undoubtedly has its place, but be warned, that spiritual nonsense can creep up on you.

Ultimately I believe it’s a simple choice. We can be seduced by the salaciousness of posture, or surrender to the selflessness of asana.

Namaste.

~

Relephant read:

Omnipresent Octopus: A Story of Our Greatest Illusion.

~

Author: Arun Eden-Lewis

Editor: Khara-Jade Warren

Image: courtesy of the author

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 4 comments and reply