View this post on Instagram

~ Warning: naughty language ahead.

Last week I watched my father die.

Alone with him in the dim room of a nursing home, I whispered a few words that ended with “you can let go.”

And he did. His chest became still and he let go.

During the following days, my family and I traded old photos and remembrances. I tried to put together a few memories that would sum up the essence of his life or illustrate something he had tried to teach us. It seemed important to fill a small mental box with key pieces of my father’s 81-year life, so that no matter what may come, I would have that.

At first it was hard to think of a story about my dad that doesn’t end with, “and then I really pissed him off…” I’ve been a button-pusher since day one, and his buttons were easy to push. That might sound heavy to someone who doesn’t know my family—trust me, nothing was heavy in my family. We weren’t grudge holders or long-time stewers. When we bickered, we walked away from it for a bit, then it was gone. Like smoke from a birthday candle, thinner and thinner until even the scent was forgotten.

My teen years were…rough.

My father often fell asleep on the couch, waking when I came home well past midnight. I would push by him, ignoring his rage. Or I would explode back at him, fiery and defiant. Those exchanges may be all that passed as communication between us for years. We had even less to say to each other after I moved out when I was 17.

I spent the next few years living with boyfriends my dad didn’t like and being just fine with that. But when I was 21 and had run out of boyfriends and money, I slouched back home for a new start. My parents watched me drag my two trash bags of belongings up to my old third-floor bedroom. They nodded when I said it was time for college. They had always known what I was capable of, but I never heard them tell me that. Maybe they didn’t think it needed to be spoken. More likely, my own swirling inner world was too loud for me to hear them.

I had no idea if I’d stick it out with school. After failed relationships and failed jobs, it seemed quite possible that I might just piece together a life of uncertainties, punctuated by fuck-ups and disappointments. That didn’t scare me. What scared me was that I might actually do well. What if I started moving toward some idea of socially acceptable success? I had no idea what that would look like, but I was sure that wasn’t a place where I would fit in. But the timing seemed as good as any, so I took small steps forward without allowing myself to think beyond the here and now.

Settling back in at home was lousy. Embarrassing. Bleak. My younger sister was heading to college, right out of high school, the way it’s supposed to be done. My teenage brother was in the midst of troubling issues that no one seemed to notice, but me. My mother walked mile after mile through the city every day, clearing her head and fighting dark clouds. And my father came home one day to say that he had lost his job.

He had worked for the same company since he was 18. His brothers had gone to college, to grad school, to medical school, pursued postdoctoral studies. My dad, the youngest, had been the high school class clown, a mediocre basketball player, a kid who hung out on the corner smoking cigarettes and cutting up. He didn’t believe he was college material. I have no way of knowing if anyone ever told him he could have done it or if he would have listened. His parents were immigrants with no formal education. They opened a grocery store under their apartment; they raised seven children. They stepped back and hoped for the best, I think.

My father believed his best option was to find a job that would pay enough to help his brothers through school. The only thing my dad knew that he could do (besides make people laugh) was draw. He started drawing when he was a toddler, setting himself up at the family’s dining room table and hollering for his siblings to bring him scrap paper and pencils. He never stopped drawing, not even after Alzheimer’s had raked through his brain in the last years of his life. At 18, he found work as an electrical draftsman and designer. He found a job creative enough to keep him happy and professional enough to come with a paycheck he could share with his family.

So for decade after decade, my dad showed up. He worked hard, a pocket protector against his chest, wide neckties, no sick days. He joined the office bowling league. He supported three children and a motley crew of foster kids while my mom stayed at home before she returned to teaching for adjunct pay. They took the small stipend they earned as foster parents and sent it to the families of the children who were living with us, knowing they needed the funds more than we did. Still, I grew up with what felt like more than enough. Before I moved back home, my parents had even splurged to have central air conditioning installed in our 19th Century row house while most of the homes in their neighborhood were still cooled by box fans and window units.

But there were layoffs at my father’s company when he was in his early 50s, and my father’s job was cut. He lost his pension. My parents’ savings were meager. The central air unit died, and my father took up residency on the couch for a long, sweltering summer.

Summer into fall; fall into winter. I left for my college classes in the morning, walking past my mute father, his head on a throw pillow, 3-day-old socks on his feet. I came home late at night after shifts as a cocktail waitress or outings with friends; I didn’t bother to say goodnight to the man on the couch who drifted in and out of sleep while the television flickered in the darkness.

At some point, my dad decided to simply open the classified section of the newspaper and try to find any job at all. I remember that he applied to decorate cakes at the local Carvel ice cream shop. My siblings and I were horrified and hysterical. We teased him mercilessly, making every Fudgie the Whale joke we could think of. The thought of our father wearing a paper hat, earning minimum wage, and working for a 25-year-old supervisor filled us with something that I’m ashamed to say felt like disgust.

Our house was often the gathering spot for our friends, and when weather permitted we spent much of our time on the front porch. Our porch was spacious and comfortable, with a huge canvas awning, potted plants, and plenty of chairs. We could play music and smoke on the porch, talking and laughing well into the night. When friends slipped into the house for a drink or to use the bathroom, they had to walk by my father, unshaven and funky. Occasionally he would yell at us to be quiet. He always worried that we were bothering the neighbors.

It just went on like that. My father caved into himself while the world spun meaninglessly around him. I barely noticed him, lost in the widening horizon of college. Professors noticed me. They pulled me aside to praise my writing. They wrote comments on my essays that filled me up with blooms of confidence that had been dormant seeds for so long. I switched majors from Psychology to English, tenuously believing that I was on some sort of path.

After a year of living at home, I moved into an apartment I hated with a male friend who was sketchy and unemployed. We had nothing between us except a few things for the kitchen, a thrift shop wicker peacock chair, a boom box, and a coffee table. We each slept on piles of blankets on the floor and pulled our clothes out of trash bags or plastic orange crates. I spent that summer dating another guy my dad hated—by the end of late August the relationship had fizzled out and I was happy to move on.

I started my second year of college with confidence and excitement, but at the end of the first week I dropped my 9 a.m. class. Late night shifts left me so tired I couldn’t keep my head up during class. Life was busy but colorful with possibilities. In mid-September, I was carrying ice buckets through the kitchen at work when I became aware that my breasts were throbbing. Back in the lounge where I mixed and served drinks I told one of my coworkers how sore I was. She looked me up and down then squinted at me before asking me the most absurd question.

The next day I came out of the bathroom at home and showed my roommate the stick I had just peed on. The moment didn’t make sense. Conflicting feelings washed over me like waves, but an undercurrent of determination formed too, growing stronger and stronger. I looked at the two lines on the pregnancy test and decided then that I was going to have the baby and that I was going to get my shit together to be a good mother. The shock and upheaval rocked the ground beneath me, but my center was firm, my focus sharpening.

I decided to move home again. Looking around my crappy apartment, everything felt wrong. That wasn’t where I wanted to go through pregnancy or bring home my new baby. Once again, I dragged a few trash bags up to the third floor of my parents’ home. Good riddance to sleeping on the floor, to smoking and drinking, even to the guy who had got me pregnant.

New beginnings it would be. New beginnings in my childhood home.

By this point, my parents were pretty unflappable. My mom was maybe a bit dubious at first, but my dad was surprisingly on board. From any angle I looked at it, my life was a mess, and at 23, I was still pretty wild and free. No one would look at me and think, “she’d be a wonderful mother.” But my dad had no misgivings. He offered me rewards every week for months after I quit smoking. He asked about my doctor appointments and looked gleefully at the ultrasound pictures I brought home. He loved that my friends and I all called the baby The Critter. The light in his eyes returned when I held my shirt taut against my belly and he watched The Critter roll and kick.

I went into labor on a Sunday afternoon late in May. I had been shopping with my brother and sister when the contractions began. That evening, it was only my father home with me while I waited until it was time to go to the hospital. Every hour or so I’d go outside for a walk, trying to move the process along. My dad declared himself the official contraction timer. Several times he’d scold me: “Maria, they were coming every seven minutes, now you’ve gone 10 minutes without one!” “Don’t tell me, dad. Talk to The Critter.”

The Critter was born on May 31, 1993, a blue-eyed boy with a strong personality. My dad’s heart turned to goo. He was smitten. He drove me bananas with anxious reminders to “hold the baby’s head” and “make sure you strap him in right.” He brought me glass after glass of water to make sure I’d stay hydrated nursing the baby through the muggy summer. He clipped a small fan onto the bookshelf near the recliner to cool the baby napping in my arms.

The winter months were brutal that year. Heavy snow, weekly ice storms, temperatures that gave the air jagged teeth. I missed nights of work and took only one class that semester. I spent countless hours hunkered down at home with an infant and my parents. If that wasn’t some sort of cosmic test for my psyche, I’m not sure what it was. The spring came like a hard-earned prize, and the days became longer and brighter.

~

Perhaps more than drawing, my dad’s deepest love was music. Friends tell me their memories of visiting my house when we were kids include my dad sitting in his favorite chair, oversized headphones on his head, with the curling cord reaching across the living room floor. We had stacks of vinyl records of nearly every genre. My dad also had a piano and an organ tucked into our living room. He had taught himself to play as a kid, without actually having a keyboard at home. He would lose himself playing and composing, asking me to write lyrics for his songs. He looked at images and saw the shapes that gave them bones. He listened to music and heard the notes and chords that cast their moods.

The music thing was lost on me. Of course, I like music. I have favorite songs and love to sing badly, dance gracelessly. But I don’t have the ear or the heart of a musician. Piano lessons for me were a waste of money. My dad’s persistence did nothing but nettle me. My son gave him a new chance to try to instill the ear that may have simply skipped a generation. With my mother at work and me at classes, my dad would spend hours with my son, playing and listening to the most grating children’s songs ever written. The PBS show Barney was on daily rotation, my father and my son singing along with the purple dinosaur, tapping out the rhythms on the arms of the couch.

My dad eventually returned to work in contracted and temporary positions for close to 20 years, sometimes commuting over an hour each way. He and my mom continued to care for my son while I worked nights and during the day until I enrolled him at my college’s daycare center. My mom pushed the umbrella stroller for miles through the city, my son waving to every stranger they passed. My dad recorded episodes of Barney and other children’s programs that he would watch with his grandson, clapping and dancing in time with the songs.

~

It’s hard to know when the dementia set in. A decade or so after I married and moved out of my childhood home for the last time, my parents sold the house and moved into a townhouse, only 10 miles away from me. As my family grew, I’d started grad school, then found a teaching position. Life was hectic in the normal ways, and in ways that were new and frightening as I learned to navigate the world of specialists that would become the norm for my youngest son who had been diagnosed with a terrible form of muscular dystrophy. Sometimes I’d go months without seeing my parents. Other times, I’d bring my three boys over for sleepovers on weekends and my parents would come to my older sons’ sporting events, my dad pacing on the sidelines or watching with cloudy blue eyes from the bleachers.

My mom recently reminded me of a phase my dad went through where he started entering all sorts of scammy sweepstakes, including many that required an “entrance fee.” We couldn’t believe what he was doing. He had never gambled, never played the lottery, and he would have been the first to tell anyone else what a stupid idea those contests were. That was a sign, but one we didn’t recognize. With hindsight, he was growing more confused and repetitive for years. It probably wasn’t until he started getting lost driving to places he’d been driving to forever that we knew. It wasn’t shocking. His father had Alzheimer’s, one brother had already lost his battle to Alzheimer’s and another brother and his sister were in different stages of the disease. We knew how it would play out though, and we hated it.

The decline got uglier and uglier before it got strangely better. We took away his car, and he would lividly call me, my husband, my oldest son in rotation, over and over again. We’d had his car for weeks, he’d accuse. He needed it! When were we going to give it back? He yelled at my mother, blaming her for the things that no longer made any sense. He wrote notes to himself on index cards that he kept clipped together in his shirt pocket, reminders that made sense to no one but, possibly, him. His mood darkened until he was nothing but a wiry field of anxious energy, lashing out before retreating into some scary cave.

He refused medical treatment for several years, until my mother, sister and I tricked him into showing up for a senior assessment at a local hospital. He tried to flee the waiting room, but the doctors and therapists there knew how to handle him. We left that day with a few prescriptions and the recommendation that my mom shouldn’t try to care for him at home for much longer. One of the prescriptions was for an antidepressant, something he would have never willingly taken on his own. By now, however, his mind had receded to a point where my mom could give him the pill daily, telling him it was a vitamin.

The medicine took effect, and he became more pleasant, less fearful as the months went by. That lasted until it didn’t. Until he slid violently from the plateau he had been perched on. He began falling, trying to leave the house at night, crazy eyed and bewildered. He spiked a fever one night, fell out of bed and couldn’t stand up. His ensuing stay at a rehabilitation hospital broke my heart.

His days there were spent realizing, over and over again, that he had been strapped into a wheelchair with an alarm. He screamed at nurses, demanding to go home. He cried out for his beloved twin brother who had died many years ago. He believed he was in his childhood home. He demanded that we take him to his childhood home. His eyes were unfocused and he spit with rage. Every evening ended with a male nurse restraining him while another nurse yanked down his pajama pants and gave him an injection of Ativan while I stood in the hallway, inconsolable.

Dark days, indeed, but there were also these vivid moments of tenderness and color that live now as some of my favorite memories. I remember my sister bringing her scissors and giving my father a much-needed haircut while he joked that he didn’t want her to ruin his good looks. My brother gently lathered my father’s face and gave him a shave while my father sat contently with a towel draped over his shoulders, lost in the middle distance.

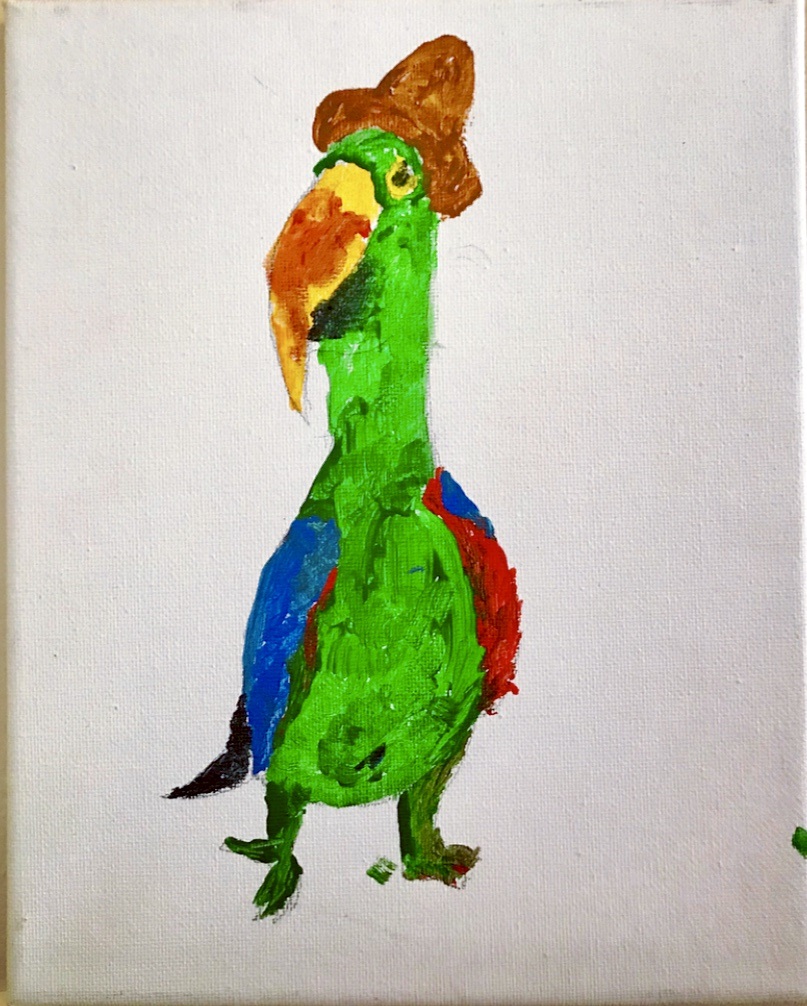

My favorite moments of those days were spent painting with my father. I brought in canvases, brushes, a few Mason jars, a bag of acrylic paints. We set up our little art studio in the common room across from the nurses’ station. For Christmas that year, I had given him a National Geographic book of photos of wild animals. I sat next to him, paging through the book, asking him if he saw any animals he wanted to paint. He stopped me at the picture of a green parrot. “I’ll paint that,” he said.

So I mixed a few colors for him on a plastic palette and handed him a brush. He worked quickly and was finished in no time. Like a child, he was easy to distract but only for short intervals. Once again he went back to trying to break free from his wheelchair, this time using the blunt end of the paintbrush to try to disable the alarm. I snatched the brush and tried to redirect his attention.

For a few minutes he sat sullenly, glancing at the parrot he had just painted—a cartoonish bird smiling and rakish in his own right. My dad was annoyed that I had scolded him, but he was also turning something over in his head. He grabbed the paintbrush back from me. He nodded with a touch of irritation at his parrot. “The parrot needs a hat,” he said. I had no idea how to reply to that, so I just watched as he dipped into the burnt sienna and gave the parrot the hat he had—indeed, I now agreed—needed. “There,” he said before going back to trying to set himself free.

He came home from the rehab center after about a week, but he had turned a sad corner in that time. The following months at home were the ugly spiral that anyone who has witnessed dementia before could see coming. By summer he began sundowning and my mother would call me or my sons, frantically, late at night. Once or twice, he slid from his chair in the living room and could not stand up. My mother couldn’t move him, so he would sleep on the floor until she could go to a neighbor in the morning and ask for help.

One night in late summer my mother called my son; my son called me; I called my sister; and my sister called my mom to say enough.

~

My father moved into a memory unit in a nursing home. He wore diapers and sat in a wheelchair all day. Some days he made sense, others he didn’t. He spent his first weeks awake all night, sitting by the nurses’ station telling jokes and making convoluted conversation, learning to feel safe under the low-hanging fluorescent lights. Days, he slept in his chair, waking to eat dinner and ice cream, then drifting off again.

He turned another corner after his first month in the nursing home—becoming an old man I had never met before—but around this corner, he had finally moved beyond the bars that had caged his mind for so long. For so, so very long. Long before forgetfulness or getting lost, my father had grown smaller as his anxieties grew and swallowed him, bit by bit. He lived so many years crawling with the itch of it but unable to put any of his feelings into words. He fought through the crushing weight of an anxious mind for so long, while I had glared at him through narrowed eyes, loathing something I sensed but couldn’t comprehend.

I can feel the weight of it now. I understand the supreme effort it took for him to fight his way off of that couch all those years ago. I recognize the impossible reality of falling in love again with a blue-eyed grandson and a purple dinosaur.

Then his life had shifted again. He spent years living in a world that changed shapes before his eyes. He couldn’t even trust the sun and moon to tell him the truth in the end.

During all that time, I saw anger. I saw weakness. I saw a person I never wanted to become. How much I hate myself for that is something I’ll consider as I learn to accept and forgive and truly say goodbye. Today, all I can say is that I see clearly now that at the root of my father’s being was fear. Fear that circled in on itself and swallowed its own tail. Fear that was too frightening to acknowledge. Fear that I have inherited and despise.

~

The last months of my father’s life were blessedly, gorgeously fearless. Ricky, the carefree class clown, made the nurses laugh every day. He ate ice cream with breakfast, lunch, and dinner. He sat with a stuffed white cat on his lap, stroking its head, eyes locked on things we couldn’t see. I want to sing this…I want to shout it.he was not afraid! Anxiety had nearly crippled that man, and dementia had tortured his mind like barbed wire. Somehow, it had magically cracked and fallen away—all that was left behind was a skinny, shriveled, happy old man with a stuffed white cat on his lap.

~

Over the winter, he started moving toward the last corner he would turn. His fought off a stomach virus that left him weak. He had a head cold. He had rallied though, so the phone call from my sister on the second day of April came as a jolt.

“Dad’s not doing well,” she said. “He may not make it.” He had another stomach virus, and he had possibly aspirated some vomit into his lungs. She was driving from her home, an hour and a half away, to see him. I didn’t work that day. If I had, I probably would have said I’d go to the nursing home after my classes. The situation seemed precarious but not dire.

I called my mother who wanted to head to the nursing home but was waiting for a repairman to finish up some work at her house. My brother planned to drive up after work. I told my mom I’d stop by the home to check on my dad, and if the repairman was still at her house then, I’d switch places with her so she could come over.

I stopped by the nurses’ desk to get a face mask before going into my dad’s room because I had a cold and didn’t want to subject his immune system to anything else at that point. I walked into his room around 10 o’clock He was asleep on his back, oxygen tubes in his nose, his white cat at his feet. He was making strange noises when he exhaled, and I felt cold and afraid. The overhead lights were off and his bed was lit by dim lamps over his headboard. His eyes never opened again, but he stirred a few times while I watched him sleep.

I’m not sure why it took several minutes to decide I should say something to him, but the thought came to like a whisper and a nudge: You should say something to him, Maria. No, you should say everything to him. Now.

And so I did.

I squeezed onto his bed, leaning my head to his ear and lowering the face mask that no longer seemed to matter. “It’s Maria,” I told him, smiling because at that point he could no longer tell my sister and me apart, but he’d usually call both of us (along with any other female with dark hair) by my name. But he made deliberate sounds when I said my name. He heard me. He knew who I was.

The realization was sharp. This might be the moment so many people wish for: the opportunity to talk to a loved one before they slip away. The chance to leave nothing left unsaid. To say goodbye.

And so I did.

I told him I loved him and that I always had. I apologized for being awful so many, many times, but I smiled then too because I knew I didn’t really need to. I knew that he had never held onto a moment of ugliness between us. That he had never expected an apology and would wave one away now. But I said it. I said things, for the first and last time, as the words tumbled out of me along with 50 years of emotions that had been stowed behind a door that had just fallen open.

“I know you lived courageously. I didn’t know that before, but I know that now. I know that you loved us in your imperfect ways, just as we showed our love with clumsy, awkward gestures.”

“You never put yourself first. Most people strive for that, but you lived it. You truly wanted your family to be happy. And we are. You are good, and you are loving, and you are loved.”

“I know that you wouldn’t want to be in a nursing home, but you’ve been so brave here. That was a gift to us. But I know you’re tired of being brave, and I know you miss your brothers. We’re all okay here, and you can let go. You can look for your big brothers at the light; they’ll meet you there. You can cross over to them. You can let go.”

I sat up and watched him pull in breaths. I fumbled in my purse for my phone and opened my music to play songs for him. I thought he’d like that. I held my phone by his ear and watched for a reaction. It took a long, slow minute before it registered, and then it came a complete thought, loud and certain.

He’s not breathing.

I ran into the hall and the nurse came the nurse listened to his chest for two minutes then the nurse stood and wrapped me into a hug the nurse told me he was gone I called my mother my brother my sister who was still driving my husband my sons he passed away at 10:40 a.m. he was gone.

~

I spent the next week pulling through the tangled threads in my head. This, I suppose, is what they call processing. It’s a mess. One thread leads to another before looping into a crazy snarl. But there’s no sense of urgency, so I pick and pull away, a little at a time.

One of the questions I considered was what did I learn from him? What did he teach me, after all? Of course, there are layers of lessons to unearth. Thinking too deeply makes me want to just stop thinking though. So, I’m focusing on the long, smooth surface of a lifetime of being a daughter to a quiet, funny, brilliant, silly, compassionate, gentle, complicated man. And what rises to the surface is his voice, a raspy whisper: The parrot needs a hat.

You were so right, dad. Most of the world would think that was ridiculous. Most wouldn’t have picked up the paintbrush in the first place. Most of the world misses the shapes that give an image its bone, and they don’t hear the music that plays so softly in the background. They don’t sit down to doodle or write a song or pet a cat. But you taught me to see the world through your cloudy blue eyes. I can hear the music, even if I can’t play it. I can see shapes and create my own images and write the lyrics you always wanted me to write. I will hold babies and animals close to my heart and make jokes to put others at ease, and I will fight like hell to beat my demons. I will live courageously too. I will fight my way off that couch and love fiercely. I will never forget to save room for ice cream. And when I see a parrot, looking green and smart and jaunty, I will take a moment to look closer and consider whether that parrot would, indeed, look better if he were wearing a hat.

Read 16 comments and reply