My sophomore year of high school, all I wanted out of life was to play Anne in The Diary of Anne Frank.

Like school children all over the world, I had felt a strong kinship with Anne after reading her diary. She kept a diary, I kept a diary. She had parents who didn’t understand her. I had parents who didn’t understand me. She was an awkward, bookish, black sheep weirdo living in the shadow of her ostensibly “perfect” older sister…

Aside from the fact that she was Jewish and had been forced into hiding to forestall being killed by Nazis along with the rest of her family, we were practically twins.

So naturally, when the very first season of my very first year of high school (9th grade was still in Jr. High back then) was announced, and the play based on her diary was the first play in that line-up, I was 100% convinced that this was the hand of fate stepping in to set me on my inevitable path to stardom.

I prepared for that audition like I was up for a starring role on Broadway. I worked my audition piece – a monologue from The Spoon River Anthology – over and over until my sister Kat literally begged me to stop. And in her defense, it was an incredibly depressing monologue (how depressing? Click the link and find out).

I went to a bookstore on the Pearl St. Mall and spent my allowance on a dog-eared copy of the play so I could memorize all of Anne’s lines in advance. That way no matter what sides they whipped out at call-backs, I would be ready.

I even went full-on method and hid out in my dad’s walk-in closet for several hours without being detected. I could have stayed in there a lot longer (I brought snacks), but after overhearing a (thankfully innocuous) phone call, it occurred to me that lurking in someone else’s closet without their permission could be construed as an invasion of privacy, and that if I stayed there long enough, I was bound to overhear something I could never un-hear. Or worse, he could walk into his closet… naked. *shudder*

Finally, audition day came. Over-prepared as I was, I still had terrible stage fright. I threw up twice, kept getting terrible dizzy spells, and my hands were shaking so hard I spilled water all down my front when attempting to drink from my water bottle. My voice quavered and broke during my monologue several times, but the pale, wet, shivering waif look kind of worked with the material, so I figured I still had a shot.

Sure enough, I got called back for the role of Anne. I was thrilled, but still felt like puking. That’s when I realized that it wasn’t just stage fright: I was sick as a dog.

But was I going to let that stop me? Hell no.

What Would Anne Frank Do?

Looking back, staying for callbacks instead of going home was an incredibly selfish thing to do. For all I knew, I was infecting everyone in that auditorium with the plague. But none of that mattered to me at the time. All the other girls who’d been called back for Anne, girls who had been my friends just moments before, were suddenly my rivals. If they ended up puking their guts out, so be it. Nothing and nobody was going to stop me from playing Anne Fucking Frank.

To give you a sense of just how far out of character this was for me, I should explain that I detest competitive games. I refuse to play Monopoly or anything of that ilk. Even Scrabble can get a bit cut-throat for my tastes, and frankly I prefer to play my own, collaborativeversion where everybody works together to try to make the longest and most interesting words possible. And team sports? Forget about it. I once hid in the forest at choir camp for an entire afternoon to avoid playing in the annual Sopranos and Tenors vs. Basses and Altos Volleyball Tournament. Still think I made the right call on that one, though.

In short: I wanted this like I had never wanted anything ever in my life before.

Despite feeling like death warmed over, I ran up onto the stage when my name was called. We started the scene. At first I was holding the sides, just as everyone else had, but my hands were still shaking so badly that it started to make a rather distracting thwapping sound. Internally patting myself on the back for having had the foresight to memorize Anne’s lines in advance, I set the script down on a chair, intending to continue the scene from memory. Unfortunately, this threw off my scene partner, who cocked his head at me and then looked out into the audience for help.

Jean Hodges, our high school director, stood up. Jean, an energetic woman with a head of snow-white hair cut pixie-short, was not naturally intimidating. But seeing her stand up suddenly like that in the middle of a scene made me stop in my tracks. Had I committed some kind of unforgivable audition-etiquette faux pas?

“Are you alright, Adrienne?” she asked.

“Yes,” I lied, trying to suppress a fresh wave of nausea, “I just prefer not to hold a script if I don’t need to.”

“Oh!” I could see her assimilating this information, but couldn’t quite read her reaction. “So… you think you can do the scene without a script?”

“Yeah, I memorized it.”

“The scene?”

Anticipating her next question, “How did you know which scene we were going to be reading?”, I replied, “The script.”

I heard a snort from somewhere in the auditorium, followed by a few nervous giggles.

“Just to clarify,” Jean said, holding up one finger, “are you saying that you’ve memorized… the entire play?”

“No way,” I heard someone whisper, but couldn’t tell if they were impressed, skeptical, or simply flabbergasted.

I put a hand on the back of the chair where I had set my script to steady myself, and nodded. After an audible gasp from the crowd, I qualified with, “Well, I mean, Anne’s lines. I didn’t memorize the entire script.” I stopped myself from adding, “That would be crazy.”

“Okay then,” Jean said, holding her hand out, palm-up, and sitting back down. “From the top, please.”

We played out the scene. Jean said, “Thank you.” We left the stage, and I promptly ran to the bathroom to throw up.

That night, I could hardly sleep. And not just because I had the runs. I kept replaying the scene in my mind, over and over again, analyzing Jean’s response and trying in vain to predict what she would do.

In the morning, I was exhausted, dehydrated, and manic as all hell. I pestered my sister into heading into school early so I could take a peek at the cast list before class. But the list wasn’t up when I arrived, so I just paced back and forth in front of the auditorium like a caged animal. Waiting.

Soon enough, though, I was joined by all the other hopefuls, and we all stood around giving each other insincere compliments until finally, mercifully, Jean appeared with a piece of paper in her hand. We all stepped back, making room for her to tape the cast list to the door. Then we swarmed.

I didn’t have to look at the paper for more than a couple of seconds to learn my fate. Anne’s name was first on the list.

And so, as it turns out, was mine.

Suddenly I didn’t feel sick any more. In fact, for just a moment, I felt as if I would never be sick again. Like I was invincible. Untouchable. Destined for greatness.

I didn’t know how to do a cartwheel, but I did one anyway. My friend Bret, who had gotten the part of Anne’s father, picked me up and spun me around. It was, hands-down, the happiest moment of my young life thus far.

When I announced the news at dinner, Kat seemed genuinely impressed and gave me an enthusiastic high five saying, “That’s awesome, AD! Way to go!”

My father, however, said simply, “Congratulations,” in a completely unreadable tone of voice, without even looking up.

This made me more determined than ever to make this the performance of a lifetime. If I could nail this iconic role, maybe I could finally make Dad proud.

Fast forward to opening night. I was home eating dinner with Dad before heading over to the theatre, looking back over the script one last time before the show.

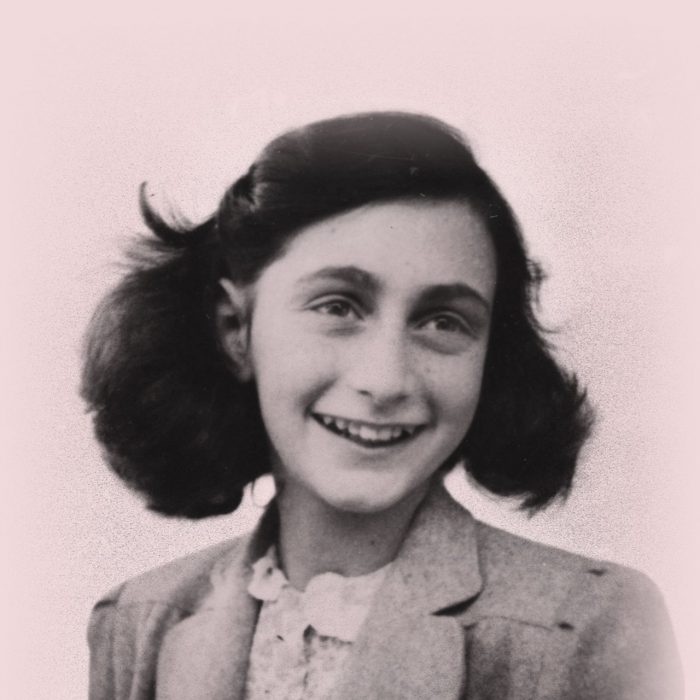

“It’s funny,” I mused, looking at Anne’s picture on the back cover, “I really do look like her, don’t I? Especially with the brown hair.” I pointed to my hair, which was normally blonde but had been dyed brown for the role.

Dad gave me an odd look. “Well, that stands to reason,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

He gave me the same look, only more emphatically.

“Well…. because you’re both Jewish.”

I dropped my fork.

“We’re both… what?”

“Jewish,” he repeated, exasperated at my obtuseness, “She’s Jewish, and so are you.”

“Dad. What are you talking about? We’re not Jewish! I’ve never even been to a synagogue…”

“You don’t have to go to temple to be Jewish. Your last name is Weil. What kind of a name do you think that is?”

“German! It means ‘because’ in German. That’s what you told me,” I protested. But hearing him use the expression “go to temple” made me realize that he wasn’t just messing with me. This surprise reveal was for real.

“Well, it is German. It’s also Jewish. And so am I. And so are you.”

Jews

There was a painful pause as I tried to assimilate this information. I had so many questions, but all I could do was stare at him, waiting for him to help me make sense of the fact that I had somehow lived to the age of fifteen without having any clue about my Jewish heritage.

Dad sighed heavily and ran his fingers over the creases in his forehead. “What do you think happened to all your relatives, back in Germany?”

“What relatives back in Germany?”

“Exactly! They’re all gone! The ones who weren’t killed off in the Holocaust escaped to the U.K. or the U.S. That’s why I was born in England.”

It was at that precise moment that it occurred to me that I would now have to go on stage to portray one of the world’s most famous Holocaust victims just an hour after learning that I am, in fact, the direct descendant of Holocaust survivors.

I pushed my plate away, my appetite lost. “Why… why didn’t you tell me?”

“I thought you knew!”

“How would I know?? Who else would have told me??”

Dad pondered that for a moment and finally said, quietly, “Well, that’s fair. My father never much talked about it when we were growing up. Definitely not in front of my mother, who was not a Jew, by the way. And since Judaism is passed maternally, some Jews, the more conservative ones, will tell you that means you’re not actually Jewish.”

“So wait… I’m not Jewish?”

“You’re half-Jewish. And, technically speaking, it’s the wrong half. But you’re still Jewish, and don’t let anybody tell you different.”

“Got it,” I said, though I most definitely did not.

“Anyway, I guess I must have unconsciously picked up from my father that it wasn’t something to be openly discussed.”

“Jesus,” I whispered.

“Also a Jew,” noted Dad.

An hour or so later, as I waited backstage to go on, I was no longer worried about making Dad proud. I wasn’t even particularly worried about what the audience would think of me and my acting (which, for me, was even further out of character than my newly-discovered competitive streak). And I definitely wasn’t thinking about how this performance would affect my future chances of becoming the next Meryl Streep.

All I could think about was doing justice to Anne and her legacy, a legacy which I had unexpectedly inherited over dinner, from relatives I never knew existed. Relatives who had been forcibly removed from their homes, starved, robbed of both their worldly possessions and their human dignity, and ultimately killed.

I wondered, as I wandered through the “attic” we had created on stage, if any of those relatives had gone into hiding, as Anne and her family had done. How much room did they have, and for how many people? How long had they made it before being discovered? And when they were, what then? Had they been shipped off to Buchenwald, Dachau, or some other concentration camp? Or were they simply shot on site?

At the end of act one, when noises are heard downstairs in the middle of the Frank family Chanukah celebration, Anne passes out cold. In rehearsals, I had particularly enjoyed that bit because I was very good at going completely limp. My mom loves to tell the story of how, when I was a toddler, I would fall asleep in the car, and after my folks had carefully brought me inside and put me to bed without waking me, I would suddenly sit up and ask for feedback on my performance.

That night, though, when I heard those sounds, and realized what they would have meant to Anne and her family, I didn’t have to act. I fell straight to the floor like a cartoon anvil. A moment later, when Bret pulled me up, I was completely disoriented. It took me a moment to realize where I was, then who I was. It took a few more moments to realize that Bret was giving me that look not only because it was my cue to start singing The Chanukah Song, but because there was blood dripping from my nose.

“Oh Chanukah, oh Chanukah, come light the menorah…” I began in a tremulous voice. Slowly, the others joined in. Bret / Anne’s father, Anita / Anne’s mother, and Lisa / Margot, Anne’s older sister. Then silence. Then applause.

The moment the curtain was closed, the others helped me off the stage and someone handed me a tissue.

“What happened?” asked Bret.

“I passed out.” Duh.

“Yeah, but… why?”

I looked at Bret. He, at least, already knew he was Jewish, though even with his hair dyed brown, he didn’t particularly look it.

“Bret,” I began in a serious tone, “I’m Jewish.”

“Yeah. And?”

I blinked.

“Well, I just found out. Like, today. At dinner.”

“I’m… confused.”

“You’re confused? Think how I feel!”

“No, I mean… how did you not know? Are there no mirrors at your house?”

We looked at each other for a moment, then burst out laughing. We were, of course, immediately shushed by the Stage Manager, but the absurdity of my ignorance was just too hilarious, and we had to relocate to the green room so as not to break curtain.

Clearly not a shiksa

Years later, I watched a recording of one of the later performances of that show. Like most of my high school performances, it was pretty cringe-worthy overall. I frequently failed to cheat out toward the audience, making many of my lines completely incomprehensible. I resorted to whiny petulance to an unpleasant degree. And I clearly had no idea what to do with my hands. But there were indeed moments of true emotional vulnerability that betrayed just how deeply I had connected with the material.

And for that, I still consider it… well, maybe not the performance of a lifetime. But a life-changing performance nonetheless.

Read 0 comments and reply