After 11 days, the first photos have been released.

Wilderness photographer Dan Broun traveled to the Central Plateau in Tasmania’s north west and hiked 4 hours through what was once a unique and thriving World Heritage Area.

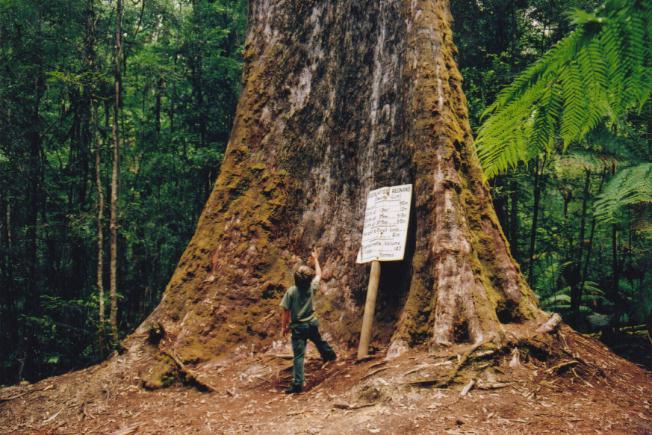

Tasmania’s old growth forests include pockets of rare and ancient pine species, including the king billy pine, an Athrotaxis species endemic to Tasmania, and the pencil pine, whose habitat sadly can not rebound from this devastating event.

Many of these trees were over a thousand years old.

Speaking with the ABC News, ecologist professor Jamie Kirkpatrick provides some important and heartbreaking perspective

“They’re killed by fire and they don’t come back.”

It is thought that a number of these forest communities had been calling Tasmania home since the Cretaceous period, and have stood sentry to a long fight for World Heritage listing in the area, providing one of the most significant reasons that Tasmania retains its World Heritage status and sees thousands of tourists flock to the tranquil bush land each year.

For over 30 years the old growth forests throughout Tasmania have been a topic of contention between loggers and environmentalist groups, as both fought for control over the hundred-year-old beings. Loggers, predominantly working for paper mills in the area, were confronted with angry protesters appalled that ancient and vulnerable tree communities were being used for paper production. The conflict became so heated that environmentalist groups erected permanent barricades at the entrances to the forests most at risk, naming the most prominent site Camp Florentine.

After finally achieving World Heritage status in mid-2014, thousands of hectares have been decimated in just over a week by lightning sparked fires.

Although this sad event has elicited grief Australia wide, it has also sparked heated debate.

Climate scientists and ecologists throughout the country and beyond have pointed a number of fingers squarely at probable culprits—namely, climate change.

Professor Kirkpatrick has stated he wants to “de-myth” this disaster, saying that despite its seemingly natural causes “this is not a natural event.”.

Fires in the area started as a result of dry lightning strikes—these differ from cloud to ground lightning associated with regular storms, as they are not accompanied by rainfall. During the dry months of summer, this effect as catastrophic, and the added wind shear of a rotating storm serves both to fuel and rapidly spread the resulting blaze.

Dry thunderstorms occur when there is so much hot air in the lower levels of the storm cell that any rain produced within the cool, lofty heights of billowing storm clouds often evaporates entirely before making landfall. This further fuels the storm, providing extra warm, moist air to be carried through the updraft and increasing storm rotation.

Climate scientists are arguing that storms such as these become more common as the effects of climate change ramp up. Warmer ground temperatures, resulting from cloudless sunny days provide the heat needed to produce dry thunderstorms. A study conducted by Princeton University in 2011, published by David Medvigy and Claudie Beaulieu in the Journal of Climate, analysed the weather patterns of the past 4 decades in terms of daily data, rather than comparing monthly averages as had been done previously. This type of analysis shows that there are significantly more extremely sunny or cloudy days now than there were just 2 decades ago, and it is these extreme conditions that create the recipe for the perfect storm.

Whilst it is unclear when or even if the forests of Tasmania will recover, climate scientists again echo a familiar warning: Ignore the science, and suffer the consequences.

~

Author: Erin Lawson

Editor: Erin Lawson

Images: ABC News/Dan Broun // Flickr/Tatters // Flickr/Scott Cresswell // Wikipedia/TTaylor // Wikipedia/TTaylor // Wikipedia/JJ Harrison

Read 1 comment and reply