What’s the real goal of yoga—to perfect the body and mind for one’s own enlightenment or to inspire a world free of stress and violence?

I once posed a similar question to Swami Vishveshva Tirtha, the head of the Madhva Vedanta lineage in Udupi, India—a saint who started practicing meditation at the age of five.

His response?

“A yogi is a fish in water. (S)he purifies the society by eating all the debris.”

Traditionally, India has always revered the yogi as a benefit to society at large. Like a fish in water, it not only depends on the water for its life, it serves to clean the water.

The ultimate benefit of your yoga practice, in other words, is that it influences a larger collective field—if you can get beyond the self-obsession that dominates the individualistic Western embrace of the practice.

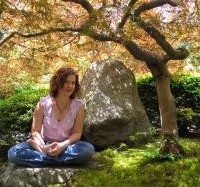

As an American yogi, I never believed that my daily yoga and meditation practice had any benefit other than what it offered my mind, body and emotional management—until I was sequestered in a remote central Indian village for three months while conducting my dissertation research.

I was staying with Nani (my best friend’s grandmother) where I shared a bed with five other women, bathed at 4 a.m. in the Narmada River (with the rest of the villagers) and helped milk the cow for my morning chai. Privacy was a luxury I resigned myself to sacrifice. And then I found it—an abandoned storeroom, which was a perfect sanctuary for my morning yoga and meditation practice. No one could bug me in there.

The first morning, I slipped out from under the leaden arm of one of my bedmates, tip-toed to my private sanctuary and unfurled my yoga mat. I relished the flow of each breath as I invoked the sun in my body. Alone with myself at last, I really missed being an American.

And then I saw them—many pairs of credulous eyes staring in at me through the windows. Where had they come from? How did they know I was here?

Ignoring the steady watch of their unflinching gazes, I continued with my practice.

But inside, I steamed with anger. Couldn’t I just be left alone for one hour? Was that too much to ask? I was really tired of being the village freak-show.

As I got up from my meditation, a sizeable crowd of onlookers who’d stared at me for well over two hours followed me as I made my way to the cowshed. They huddled around me requesting many things that seemed strange and out of place:

“Can you come to my field later today and bless my crops?”

“My auntie is very sick. Could you pronounce a mantra to help her get well?”

“Our daughter is getting married. We’d very much like it if you selected the proper bridegroom for her.”

I thought these people were out of their minds, until Nani explained something that changed the way I viewed my yoga and meditation practice.

“You are a yogini and you’ve come to this village. Because you are here, the people believe that the rain will be not too much and not too little this year. The fields will yield more food than we can eat. People won’t argue as much with each other. And we’ll all enjoy good health.”

The body of the yogi, Nani further explained, is a channel for the Divine to come through. The yogic practices purify the mind, emotions and ego until the individual sense of self dissolves. Ultimately, the presence of a yogi is a conduit for peace and non-violence.

“It’s said in the days of Buddha,” Nani concluded, “that his aura spread light across thousands of kilometers attracting followers with its magnetic non-violent vibrations. Kings stopped fighting wars and became monks. And India enjoyed hundreds of years of peace.”

In a real yogi’s presence, in other words, all violence gets subdued.

Hostile animals and people lose their aggression. A higher principle of peace dominates the collective instinct, which in its lowest expression is geared toward self-preservation and survival of the fittest. Yoga is ultimately an evolutionary system—to raise society at large up from its basest tendencies.

If this true, then why with so many people practicing yoga in the Denver area alone, did the worst public shooting in American history take place in its own backyard?

Perhaps we yogis have our focus in the wrong place. Perhaps the practice of yoga is too me-driven, when it’s really meant to surpass the demands of “I” and “mine.”

Maybe the shootings in Aurora are a wake-up call to really put our yoga to work for the collective good as it’s been traditionally regarded for thousands of years in India—the only country in world history, I might add, that won its independence from a major colonial power without firing a single bullet.

Because Gandhi was a yogi.

~

Editor: Brianna Bemel

Like elephant Enlightened Society on Facebook.

Read 72 comments and reply