We all make choices—adopt beliefs—that alter the trajectory of our lives.

Some of these choices have long lasting consequences. One such choice has to do with whether we frame things in a binary way, such as “us vs. them,” or whether we frame things based on the notion that “we are all in this together.”

Do you identify yourself as being alone, or together with others?

I’ve been exploring this question recently as I read My Promised Land by Ari Shavit. It’s a beautifully written book that tells of the triumph and tragedy of Israel. Shavit’s great-grandfather first visited Israel in 1897 and he was one of the founders of Zionism, which supports Jews in maintaining their Jewish identity and creating a Jewish homeland.

As Shavit revisits Israel’s infancy, he tells of the early decades of the 1920’s and 30s which were exceptionally good for the Jews of Palestine. The economy was booming and the culture was blooming. As Shavit writes, “Their life experience is that of an astounding collective success, based on self-reliance and innovation.”

But, then things change as a result of a civil war from 1936–39. The Jewish leadership and Jewish community as a whole adopted the belief: “us or them, life or death.” Innocence was replaced with innocent victims—Jews killing Arabs and Arabs killing Jews. As a result of adopting an “us or them” perspective, the Jews in Israel have lived embattled ever since.

Choosing survival, but at what price?

It is possible that if the Jews hadn’t adopted an “us or them” perspective they may not have survived. But, paradoxically, as a result of adopting such a perspective they assured themselves a life of continual conflict and anxiety about their survival.

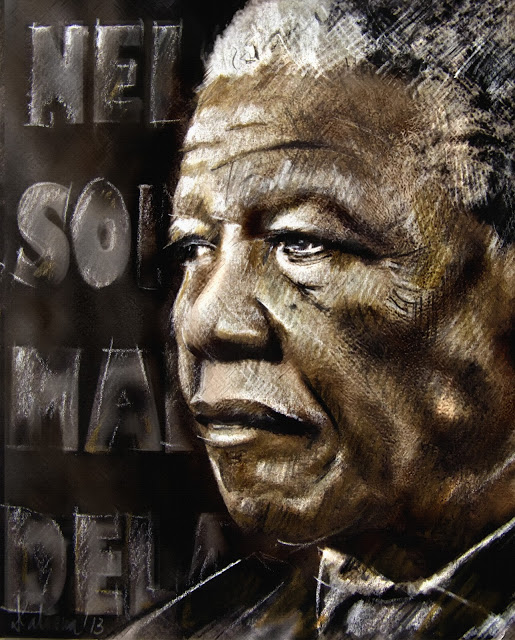

An alternative approach can be seen in the actions of Nelson Mandela who chose not “us or them,” but “all of us together.” He insisted that domination—white over black or black over white—was not an option. How did he arrive at such an enlightened stance?

Some say that it was because he embodied a remarkable capacity for forgiveness. Personally, I do not believe it was forgiveness, but pragmatism. He chose the path that promised the greatest hope—not just for his people, but for all people.

27 years in prison.

Although angry when he went to prison, he matured while in prison and by time he was released he was able to see the long view, which is a characteristic of maturity. He knew that an “us or them” stance would result in retaliation and endless struggle.

Instead of “us or them” he elevated the conversation and promoted an understanding that differences between people do exist and only by respecting those differences, not resenting them, would the South Africans find peace and eventual prosperity.

These histories of Israel and South Africa will play out for generations to come. The choice of “us or them” looks ominous, the choice of “all of us together” looks auspicious.

Do you imprison yourself?

And we each make a similar choice in our own lives, in our marriages and other important relationships. We can see the world through an “us or them” filter and therefore stimulate fear, defensiveness, aggression, and alienation. Or, we can see the world through an “all of us together” filter, thus stimulating understanding, cooperation, openness, and connection.

Where does the “us or them” perspective come from?

I believe it comes from the most primitive parts of our brains, the survival circuits. When we feel threatened we reach for the only tools our primitive brains know: fighting, fleeing, or freezing. You may think you don’t do these things, but when you insist you are right and you make other people wrong—that’s your fighting circuitry. When you walk out of a room in the middle of a conversation, or simply stop listening—that’s your fleeing circuitry. When you paralyze yourself, stop expressing your true feelings or go into confusion—that’s your freezing circuity.

Us or them. Good or bad. Right or wrong. Black or white. All of these overly simplistic distinctions stimulate the fear centers of our brains.

If we learn to make finer and finer distinctions, which is a sign of greater intelligence, we activate the more advanced parts of our brains. This is precisely what happens when we learn to use ReSpeak. We slow ourselves down, we become more deliberate. We see every situation is comprised of multiple perspectives—as many perspectives as there are people. We stop telling other people about them. We stop trying to control other people.

We become more vulnerable and in doing so we connect more deeply with other people. We recognize our differences while feeling our similarities.

This was the choice that Nelson Mandela made.

And he advocated that Jews make a similar choice. He once remarked, “We know too well that our freedom will be incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians.” And at the same time he acknowledged that the formal recognition of Israel as a Jewish state was an essential ingredient for peaceful co-existence.

Some people have referred to Madiba’s philosophy as the philosophy of “yes.” I encourage you to bring this philosophy of “yes” into your life and your relationships. When there is tension, always ask the question, “What can we say ‘yes’ to?” My wife, Hannah, and I always revert to these simple questions when we experience tension in our relationship. We ask,

“Are we friends?”

“Do we love each other?”

“Do we want to reconnect?”

Because we answer these questions with a resounding “yes,” we re-establish a loving connection. It works every time.

And, if the philosophy of “yes” seems a bit too vague—which I think it is for many people—I recommend that you practice these three communication skills which will lead to greater understanding:

1. When there is tension in your personal relationship and you need to clear the air, ask the questions listed above. If you don’t choose to reconnect, postpone having a conversation until you do desire to reconnect.

2. Restrict your conversation to talking about what is happening right now. How do you feel right now? What do you want from the other person right now? What are you asking the other person to consider right now? Don’t talk about historical matters, like who said what or who did what when. Just accept that you have different experiences of what happened.

3. Take responsibility for what you feel. Instead of saying, “You make me angry,” try saying, “I’m angering myself.” Instead of saying, “You embarrassed me,” try saying “I embarrass myself.” This way of using language—verbing—was written about in a previous elephant journal article, Changing Our Language Can Change Our Lives.

And, finally, if you are relating with other people who choose to see the world in black and white terms, and who choose to think they are right by making you wrong, and who do not deeply care about how you feel—then you may not be able to rise above those severe limitations and practice a different approach.

You may need to remove yourself from such relationships—even if they are familial.

Choose yes.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Photo: Daliana Pacuraru/Pixoto

Read 7 comments and reply