I write a lot about my brother Will’s death at 21. The day when the phone rang and I heard my mom say dark, foreign words like coroner, needle, heroin, autopsy, was the most impactful day of my life.

Putting my story out there means I sometimes get emails from readers who share that they have also lost a brother or sister. They talk about not knowing how to move on, the immensity of their grief, and the pain of watching their parents suffer. I instantly feel a connection with the person writing to me. It brings me back to the first months and years after my brother died, to the freshness of being without the person I was supposed to walk through a lifetime with.

“Be strong for your parents,” said blurs of people at Will’s memorial service. I nodded, but inside me, something twisted. I was 24, and in a daze as people streamed by, offering their awkward words and hugs. Be strong for your parents? I thought.

I am barely breathing. I am barely standing here. Strong is the last thing I feel.

In the early months after Will’s death at 21, I existed in a heavy fog. Nothing was as I knew it. I’d abandoned the little life I’d started in Maine and landed back in Alaska where my parents were, where my brother and I had grown up. My friends were living their lives– going to college, working, falling in and out of love and lust. Meanwhile, my life had stopped.

My childhood home was filled with the cloying scent of flowers just starting to die. It struck me then how terrible it was that we send flowers to the grieving—here you go, another reminder that nothing is permanent, that everything lovely will be lost.

My brother’s absence was heavy in the house. Though he had died in Seattle, his room was scattered with relics; the bed he had slept in for so many years, his big flannel shirts hanging like shadows in the closets, a handful of videos and books. Memories pinned to each corner.

Having always taken comfort in words, I scoured the internet for a book for someone like me—an adult whose (barely) adult brother had died. What I found was unimpressive: there were more books on losing a pet than losing a brother or sister. A few books existed for surviving children after a death in the family, but they were for small children. One memoir documented a sister’s grief following her brother’s death, but it was out of print.

What did it mean that there were no handbooks for me? That people asked me to be strong in the face of the biggest loss I’d ever experienced or imagined? At times I felt like I didn’t deserve to feel so shattered, especially in the shadow of my parents’ immense grief.

A few months later, I started attending a local grief group. I sat in a circle with a few widows and widowers, a woman whose daughter had died, and a woman whose mother had died. I was younger than any of them by at least thirty years, but I could relate to their shares: “I feel like I’m going crazy.” “I’m so damned angry right now.” “I can’t sleep at night.”

Though the losses were different, the feelings were the same.

So much was lost.

My parents, who would never be the same. Their pain was almost visible, as if a piece of their bodies had been cut out. I had lost myself, too, or at least the version of me that was unscathed by tragedy: an innocent version, who walked around in some parallel universe where her brother was still alive, ignorant to the incredible fortune of an intact family.

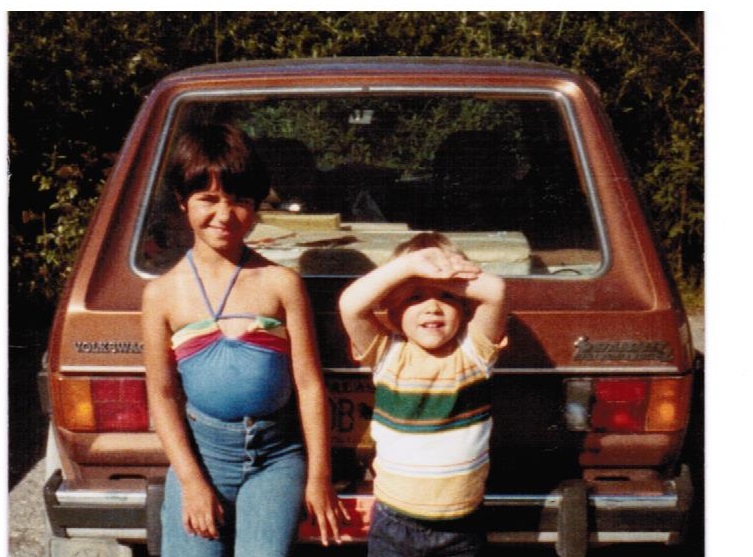

My brother, my past. Will’s big blue eyes. His loud laugh. He was the co-keeper of my childhood. The person who was supposed to walk with me longer than anyone else in this life. The only other person who knew what it was like to grow up with our particular parents, in our particular home.

The future. I cried for the nephews and nieces I would never have. I cried for my own faceless potential children who would never know my brother. How would I explain him? How would I ensure that his essence wasn’t lost, that he wasn’t just a figure in old photographs, a handful of stories? And I had to have children someday, right? I was the only person who could make my parents the grandparents they always assumed they’d be.

And all the hard times ahead when my brother wouldn’t be by my side. When my parents began to age. When my grandparents died. There would be no one to share these dark milestones.

I felt like our family had been a four-legged table, and one leg had suddenly been torn off. The remaining three of us wobbled and teetered. We felt the missing leg like an amputee, each morning waking to the horrible fact that Will was gone.

I wrote letters to my brother in those early months and years. At first, memories blazed through my head and I used the letters to capture them before they flitted away, gone forever: my brother walking towards me when he visited me in Maine, the sun splattering his cheeks, turning him golden. The time I taught him to make snow angels in the front yard of our childhood home, our bulkily clad limbs sliding in synchronicity under icy stars. My tiny hand on my mom’s belly, feeling my brother kick.

Later, I wrote the letters when I needed to cry—when the grief sat coiled and waiting in my chest, needing to be let out, released. I couldn’t find the words of other bereaved sisters or brothers to bring me comfort, so I created my own.

One day, when I was lost in my sadness, my mom said, “You won’t always feel like this. You’ll have a family of your own. You’ll move on.” This seemed impossible in my 24-year- old skin. I couldn’t imagine this potential future my mom spoke of, this invisible, imagined family.

But very, very slowly, I began putting my life back together. I finished college. I made the difficult decision to leave home again and move back to Maine. I met my husband and after several years, we had two children. Our son has my brother’s big blue eyes and his love of music. Our daughter possesses the lighthearted spirit my brother had at the same age. The sibling love between them is palpable; they spat and giggle, they dance and huddle. I pray that they remain close as they grow, and that they get a lifetime together.

It’s been fifteen years now since Will died. The sharp shock and grief I felt in those early months and years are gone. It took years for the pain to fade, for the words “your brother is dead” to stop pounding in my head—but they did. Will’s absence is mostly a dull hurt, the ghost of an old broken bone that aches when it rains. I feel it more on holidays and anniversaries, when someone close to me dies, or when I hear of a death similar to his.

I’ll always wish he was still here. I’ll always wonder what he would look like and what he’d be doing if he was still alive—at 36. At 50. At 75.

I move on and through. Perhaps I am even strong, like those well-meaning mourners at my brother’s memorial asked me to be. But my brother’s loss will remain with me for my whole life—just like he was supposed to.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Jenna Penielle Lyons

Photo: Courtesy of the author

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 105 comments and reply