Visiting friends in a New England college town, I encountered a sizable student protest aimed at ending the Indonesian occupation of East Timor.

When I asked a non-participating student why the group wasn’t protesting against, say, a large mill right there in town that was threatening to send local jobs out of the country, she explained that, “They can’t get laid doing that.”

Apparently, advocating for the jobs of people close enough in space to run into you in a bar, and distant enough socially for you to wish they wouldn’t, just isn’t sexy. Townies aren’t sexy. Advocating de haut en bas for exotic people you will never meet, and in whose day-to-day struggles you run no risk of having to share—is.

Sadly, this truth is nothing new; Charles Dickens pointed it out in 1838:

(S)ympathy and compassion are every day expended on out-of-the-way objects, when only too many demands upon the legitimate exercise of the same virtues…are constantly within the sight and hearing of the most unobservant person alive. In short, charity must have its romance…and the less of real, hard, struggling work-a-day life there is in that romance, the better.[1]

The media are only too glad to supply romantic objects for our sympathetic impulses. How many six-year-old girls are killed in our urban slums and depressed rural areas every year? How many of them die as victims of standard-issue domestic abuse, or as collateral damage in run-of-the-mill urban violence? How many of them are poor, nonwhite, unattractive-by-media-standards, and inconsequential to the core advertising target demographic? How many can you name?

Now: how many six-year-old beauty pageant contestants from wealthy families are murdered under  mysterious circumstances, and are still talked about in the media nearly twenty years later? How many times have we seen their precociously coiffed golden tresses in the grocery market checkout line?

mysterious circumstances, and are still talked about in the media nearly twenty years later? How many times have we seen their precociously coiffed golden tresses in the grocery market checkout line?

What it takes to get our sympathy and attention is glaringly clear:

Media coverage of the case has often focused on JonBenét’s participation in child beauty pageants, her parents’ affluence and the unusual evidence in the case.[2]

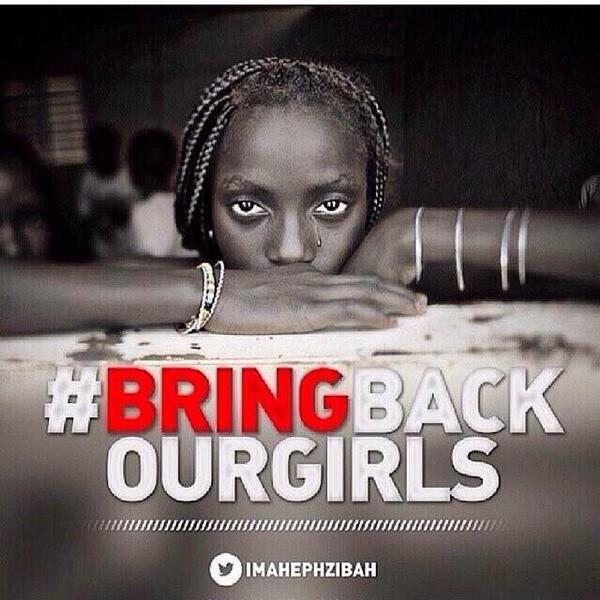

How do we raise awareness of the plight of over two hundred girls kidnapped from their school in Chibok, Nigeria? We might emphasize that their kidnappers were motivated by opposition to Western education; the insult to us will likely generate more sympathy for the girls.

We might start a Twitter campaign, and use heart-tugging images of photogenic African girls to publicize it–girls from Guinea-Bissau, over a thousand miles from Nigeria, who aren’t wearing any off-putting Islamic attire. We could re-tweet.

Or we could actually go out of our way to shop at locally-owned businesses that pay a living wage. We could march in a demonstration. We could host a homeless family in our home or church. We could exercise actual charity.

The English word “charity” is derived from the Latin caritas, the word used to translate the Greek word agapé—which means “unconditional love.” (It is similar in this respect to the Sanskrit maitri.)

The word is used to describe the way God loves us and is, along with fides (“faith”) and spes (“hope”), one of the three cardinal virtues of the Christian life.

But unless we are actually feeding the hungry, physically standing with those who struggle for a living wage, visiting the sick, cleaning up the streets or parks—anything that does good in the real world, that makes efficient use of our energies and is not calculated to raise our own cachet—that makes a measurable difference in our own communities and to the people among whom we live, who may be neither photogenic nor exotic nor inaccessible—unless we do anything like that, we run the risk of merely gratifying our own vanity at the very moment that we tell ourselves we are practicing charity.

[1] Dickens, Charles. The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_of_JonBenét_Ramsey

Read 0 comments and reply