I couldn’t keep from crying; the sadness kept coming in ever-increasing, confusing waves.

I had biked to work in the morning as usual, only to have to leave work after a couple of hours.

The transition into Fall has been triggering sadness and regret in me, but I couldn’t get a firm grasp on why it was so intense this year. My usual bike ride to work that morning was filled with tears and feelings of dread every time I looked up at the changing colors of the leaves on all the trees.

I found myself avoiding looking up at the trees—the exact opposite of my usual joyful practice.

Autumn used to be my favorite season, but in the last few years, I’ve noticed my reaction to the season becoming progressively sadder each year.

I’ve been obsessed with death and dying for the past few weeks. I even completed my Five Wishes, Living Will and shared it with my daughter. And while I recognized I was obsessed, I couldn’t figure out why, even though I was constantly searching for the answer.

I hadn’t been sleeping well, and when I did get to sleep, I was waking up too early and couldn’t go back to sleep. I love sleep, and I usually sleep a lot, so the sleep deprivation that was piling up was no small problem.

I could barely express my need to leave work, I was so overcome with grief and sadness. When I left to go home, I took my usual bike route down by the river, thinking it would assuage the grief and comfort me into healing as it usually does.

But I discovered that was not the case that day. In fact, as I squatted by the moving water, sheltered from view from the bike trail by the high, sandy riverbank against my back, I found the grief multiplying, and I was growing more desperate. I felt panicky.

With my face against my knees, I sobbed seemingly endlessly, my body jerking and pulsing with the those deep, silent sobs that rhythmically shake the entire body, and I was grateful for the river’s rush and roar to cover the noise of my loud, ragged, intermittent, desperate inhalations between those silent bouts of shaking.

I couldn’t seem to stop crying; there seemed to be no end to the sadness. At one point, some autumn leaves fell into the water in my line of sight, landing on the water to be whirled downstream by the river. That’s when it hit me. My sister’s death—her murder—twenty-three years ago, had occurred in autumn.

But how could this be effecting me so severely now, so long after the fact?

I suddenly and spontaneously began experiencing the shock and grief I remember going through when her murder actually happened all those years ago. I felt the panic at not knowing how I could continue life without her. I felt the hopelessness at knowing I would never see her again.

I found myself angry at the leaves for changing color and falling. If the leaves would just quit fucking falling, all would be well! I was sure of it! I cursed the leaves, yelling at them as I stood there by the river to stop falling, gawd damn it!

We had plans together; she couldn’t be gone yet. We had always said we’d live near each other and raise our children together. We’d run them all outside each morning to play and then just hose them down at the end of the day before herding them back inside for the night, not really keeping track of who was where—just as long as everyone was happy and fed, healthy, sleeping and loved at the end of the day.

We said we’d grow old together, and sit out on the back porch, drink iced tea and gossip, laughing at the memories of our early, wild days—the copious amount of alcohol consumed during our college years, the basketball and football games in high school, cheerleading, almost burning the new gym down, growing up on the farm, hoeing cotton, sitting in the sweltering heat under a swamp cooler shelling peas to get them all frozen and canned for the winter with all the women in the extended family, riding horses, showing pigs and lambs at the stock shows, riding our bikes down the dirt road to visit the two Keith boys and play 2-on-2 baseball with them.

Everyone always knew that whoever had Mickey on his or her team would win; it was just a historical fact. But we also knew Murray, the younger, funnier one, on the other hand, would elicit more laughter. Which one to choose? It was the usual pleasant dilemma.

We’d grow old together and have way too many cats and maybe we’d even die together on that back porch, sitting in the shade and just nod off back into the infinite again, keeping each other company even then.

At the river, the panic growing ever stronger, I was beginning to worry it would never stop—the same sensation I had those 23 year ago. Some sane part of me recognized I needed help, but I was unable to focus, so didn’t know from where it would come. Panicked, it was getting more and more difficult to herd my thoughts in a good, positive direction and think; I was getting desperate.

And suddenly I knew where I needed to be. Fortunately, it wasn’t far away either. I jumped on my bike—tears, snot and sobs still all flowing freely and headed for church.

My problem was this, though: I did not have a phone or a watch, so I had little idea of the time. It was a weekday morning, and I knew the office hours, but didn’t know the current time, didn’t know how long I had squatted there by the river.

So I didn’t know if the office was still open or not—didn’t know if anyone would still be there. I tried not to think about the possibility of it being empty already—that only brought more panic.

I just pedaled—and bawled.

At one point on the way there, I was surprised to heard my own voice and realized I was praying out loud like I was repeating some sort of chant or a rosary of sorts, “Pleasestillbethere. Pleasestillbethere. Pleasestillbethere,” repeatedly and over the top of sobs, loud, jagged in-sucks of labored biking breath and wiping snot on the back of my gloved hands.

I met plenty of people—in cars, on foot and on bikes. I was careful to avoid eye contact at first, but then lost all semblance of propriety in my desperation, gave up caring and continued chanting/praying and crying.

I’m certain I was scary. I’m glad no one stopped me. I was incoherent by then anyway and couldn’t have explained anything to anyone.

I finally reached the church and felt relief flood through me to see Peggy and Leane’s cars still there. I dismounted and ran in, calling for Leane. When she looked up from her desk at me, a stray, coherent thought wormed its way to the surface, and I knew my wild, hysterical state would scare her.

I didn’t want to scare her, but the only thing I could think to say as she ran to me to take me in her arms was, “Madi (my daughter) is okay,” just before she enfolded me.

Then all hell really did break loose, because I finally felt safe enough in her arms to soften enough to allow it an opening— to let it come get me and take me away.

I wailed and sobbed and cried, and the pain and intensity of it doubled me over into her body, my chin on her shoulder, as she took the weight—both emotionally and physically.

As Leane held me, I remembered how at the news of her death, we had traveled to my parent’s house and then to the funeral home. And I saw my sister in her coffin for the first time. At my reaction, Joey, her husband, grabbed me and kept me from falling. I realize now he was expecting that, had stood there for that very purpose, ready.

He held me tightly and securely as I cried and struggled against him, unable to cry politely at the sight of her marred face, by the attempts to stitch her freckled-face beauty back together, showing the scars that would never heal, never need to.

It was not easy to look at, but I remain grateful that I got to see her lifeless, scarred body. I needed to see her that way to be able to believe it, somehow.

I knew he understood my reaction to seeing her. His sad, determined firmness as he supported and held me told me this. I knew he was already in the place I was just entering.

Did he feel, like me, as if he had failed her? I was the big sister; it had always been my job to protect and shield her from harm.

I felt like I had let her down; I hadn’t been there when she needed me.

My mind returned to the church office as a part of me registered that someone else was there with Leane and I. Someone had come to help and had their hands on me, one hand on my heart in front and one in back.

Whoever it was held tightly, pressed hard. I needed that pressure. Needed the support. Needed the strength to hold me together, because I felt like I was flying apart, little pieces of me spinning off and out in all directions.

I could feel that person breathing deliberately, pumping that breath and energy into me through her hands, through her prayers. They shuffled me in this manner to Peggy’s office and sat me down, still holding me, still breathing for me.

It was only then that I realized it was Peggy breathing for me.

Finally, the panic and depression lessened some and I looked up at them and tried to explain. They sat with me, quietly and sweetly, listening to my memories and stories, asking gentle questions—just absorbing—letting me work my way back to something like normal for me.

I eventually ran out of stories, memories and energy; I felt dry and used up—empty and exhausted. It was a blessed feeling to be so empty after having been way too full of grief. I thanked them; I can’t express enough gratitude to them for their kindness and love and patience.

I rode home somehow—I don’t remember the journey—crawled into bed and slept for three hours.

A friend called me later and when I told him what had happened, he suggested I had been ambushed by grief. I had never heard that expression before, but instantly when he said it, I knew it described my day—in fact, it described the slow sneaky ambush that had been approaching for several weeks and had only finally just pounced. I could see it in hindsight.

Saturday I called my daughter and told her I was basically useless, but that I wanted her to come to lunch anyway as we had planned because it had been so long since I’d seen her.

I needed groceries and wanted to wait until the crying stopped that morning before going, but it never did, so I ended up going to the grocery store and walking around shopping while bawling still.

I didn’t know what else to do. How was I supposed to do my life? How am I supposed to do my life?!

While doing research on the subject of being ambushed by grief, I must admit to not finding a lot of information. But I came across a blog that describes it thus:

“Even as I write now, I continue to learn that grief is not a short-term spiritual, emotional, mental and even physical struggle that you just “get through”. Perhaps, this will be a lifelong journey until I reach my eternal home.”

Another one:

“You will be ambushed by grief. Count on it. If you have ever experienced any sort of loss or heartache in life, grief will surprise you from time to time.

Sometimes you can come to expect it, and then you’re somewhat prepared. Sometimes not.”

How am I supposed to do my life now? How long will this continue? Will this happen every Fall? I am trying to honor this grief and my sister by allowing myself to feel the emotions that perhaps I never allowed myself to feel before.

Why else would they return so strongly, so insistently?

I don’t understand it, but feel I must respect it as best I can and just somehow continue to walk through it. I am grateful to have such a wonderful group of friends to help with this trek.

Have you experienced a grief ambush? How did you handle it? Does it continue to happen? Is there any way to prepare for it?

I need your input.

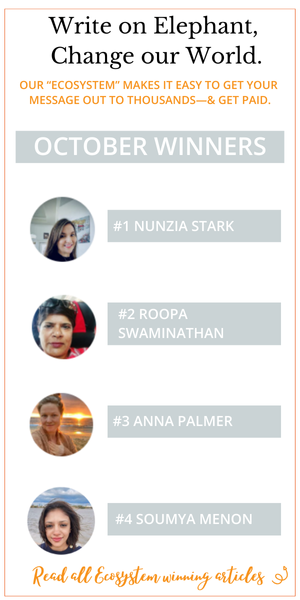

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Renée Picard

Photos courtesy of author

Read 4 comments and reply