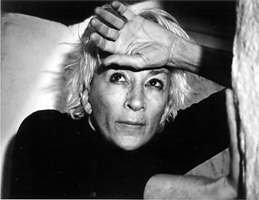

This is part one of a three-part series from award-winning dance performer and director Ruth Zaporah. At age 17, Ruth’s father gave her Autobiography of a Yogi to read. Ever since, she has maintained her devotion to both Eastern and Western practices and understandings of the mindful process, and has applied them in her innovative work in physical theater improvisation training. “A Mind in Three Episodes” is excerpted from her new memoir, Improvisation on the Edge.

˜˜˜

Many years ago a meditation teacher from Tibet suggested a lovely practice.

“Lie on the ground,” he said, “and cast your gaze up into the clear sky. Relax and do nothing else.” Another practice with which I’m even more familiar is to sit in front of a white wall with the same instruction: do nothing.

However, the most deeply and consistently visited practice, the one that has occupied me for the last forty years, is to stand in front of an audience and do nothing.

Nothing? How can that be?

How can a show proceed with me, the only person onstage, doing nothing?

The answer depends on how we consider the word “do.” Imagine a show that determines its own images, characters, voices, and actions. Even the sequencing of events is of its own choosing. In a mysterious way and with a gentle hand, the show leads the improviser through unexpected territories. For this to happen, the improviser must be relaxed, open, and willing. He or she must feel the cues, listen to the invitations, hear the hints, and move with the pulls. Improvisers learn that this is the easy way to go, this way of no resistance. They implicitly trust their craftsmanship, so why resist? On the other hand, “do” means effort and rushes to the rescue under the threat of doubt, con-fusion, or hesitation.

It thinks it’s “saving the day.” But it only causes exhaustion and usually a dead show.

All three of these “do-nothing” practices share a common center. Both the clear sky and the white wall present no content other than what they are: empty landscapes. The stage is also an empty land-scape until something happens on it. Each distinct practice provides an opportunity to examine the mind, to see how it operates, and to track its patterns.

Over time it becomes evident how our minds, starting from an empty landscape, skillfully (and sometimes deviously) construct the world we live in.

Different forms of meditation practice offer their own ways of helping us see how we get entangled, obsessed, fixated, and blinded by our busy, constructing minds. One meditation instruction may tell us to relax and become spaciousness itself, even as images, thoughts, sensations, and feelings pass through one’s mind. Another may advise us to distance ourselves from all that arises by noticing and then labeling thoughts, feelings, and sensations. And yet another instructs us to block these arisings by “cutting off the mind road,” by refusing to engage with them at all.

The practice of improvisation offers a fourth possibility: to embody the arisings, and with imagination to actively engage with the images, thoughts, feelings, and sensations as they arise. This engagement demands a clear perception without the constraints of attachment and identification, both of which blind us to the true nature of each moment.

Here are some examples that demonstrate how, given the same scenario, our mind activity can differ radically.

The first way of experiencing is something we are all capable of, some of us rarely and spontaneously, while others cultivate this way of experiencing through practice. I emphasize the “-ing” in the word “experiencing” because there is neither a subject (an “I”) nor is there an object (a “that”). There is only experiencing.

Suppose I’m standing in an open pasture alongside some railroad tracks. I’m gazing into a landscape of flat, golden, grassy fields. The landscape and I are merged into one experience. There is no sense of an “I” looking out at an “anything.” A train approaches. The metal beast and my fragile bones share in the consuming vibration.

Car after car, color after color goes by. What goes by? The train? Me? Or is there just “going-by-ness”? We recede, the train and I, as I am once again the flat, golden, grassy fields.

Another way of experiencing is when we get lost and fail to maintain present awareness; when we identify with what we perceive and everything becomes self-referential. When there is an “I” and a “that.”

Suppose one of those cars has animals in it. I make an assumption that the animals are being taken to slaughter. I become overwhelmed with sadness. I think about becoming a vegetarian while knowing that I probably won’t, and then I take myself to task for making such a false promise. Then I think about all the needless cruelty to animals and my breath quickens. I imagine joining a demonstration, maybe sitting at the entrance to a slaughterhouse. Then I think about capital punishment, and then the electric chair, and on and on I go. No lonher do I remember where I am, nor do I notice that the train and its faded, colorful cars have passed me by.

Here’s yet another option, which essentially describes the heart of improvisation—an embodied translation of the mind to the stage. The relationship with the landscape has no limits. I embody the landscape as I become it, in flesh, bones, and breath, in dance, song, and text. I speak of its history as I become a trapper who passes through this territory and settles down to build a homestead. I then become a train huffing and screaming through a narrow mountain pass carrying goods toward the western cities.

I become an animal, packed head to tail with other animals lurching and rolling against one another in the fetid, too-small container. I lament my fate in song. I become the car, my arms squeezing the animals together in violent stabs. I sing to the animals as I lay with them on the conveyer belt as it heads toward the mouth of slaughter. It goes on and on.

I play endlessly within the fantasy of landscape, train, car, animals, death, air, song, and sky.

How can a clear-sky mind get involved with the train, the death, and the air and not lose touch with time and space, never slip out from the body and its present conditions? As the veil of cluttering mental activity lifts, what was previously thought of as “real” becomes open-ended and without boundary. What was seen as permanent is now seen as transient, subject to the context of the moment, subject to everything it is connected to.

What was seen as the solid context of the moment is now seen as a playground with a kaleidoscope of changing events, colors, movements, and histories. Everything can be messed with and reinvented, and it is all just as real as our ideas of “mother,” “father,” “love,” and “cities.” The imagination, the visionary, sees infinite realities.

~

From Improvisation on the Edge by Ruth Zaporah published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2014 by Ruth Zaporah.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Editor: Renée Picard

Photo: Vancouver Film School at Flickr Bio photo of Ruth by Lynda Rodolitz

Read 0 comments and reply