One of the greatest insights offered to us by the buddhadharma is its explanation of the source of life’s stresses and miseries.

No, the bulk of our suffering doesn’t derive from external events, such as wars or crime, as we are living in the safest era of our species existence, with a remarkable decline in violence as Steven Pinker has conclusively documented.

Nor do lost relationships and abandonments exact the greatest toll.

Our suffering derives from our species’ delusional desire to avoid life’s inevitable emotional discomforts.

Essentially, we crave an escape route from difficult feelings and moods. We all work from the same universal, basic emotional palette: anger, fear, sadness, happiness, disgust, contempt, surprise. (Check out the work of the pioneering American psychologist Paul Ekman for the extensive research documenting the universality of human emotions.)

Negative emotions are as essential—and as embedded into the human psyche—as the positive.

Now, before we continue, let me note that in the cases of unbalanced amounts of depression or rage, where those energies consume our daily lives and lead to poor functioning in relationships, it is entirely appropriate to seek professional help to restore emotional balance. But many of us seek to disrupt the natural flow of positive and negative feelings, turning away from and suppressing our darker feelings as they seek our attention.

Alas, many of us are trained, in the formative years of childhood, that some of these inevitable emotional states aren’t particularly safe to express, such as sadness and anger: they must be avoided at all costs.

For example, as infants, we run to our caretakers during difficult emotional activations, seeking understanding and soothing. If our caretakers are tolerant of fear, we learn how to regulate fear when we experience it. But if certain emotions make our caretakers uncomfortable, we’ll struggle when they arise throughout our adult lives.

In my family, anger was never properly modeled; my father, for many years a violent alcoholic, didn’t know how to sit with disappointment and express it safely, and so through much of my life I attempted to use meditation as a way to avoid anger, rather than to learn how to feel it in the body, allowing it to arise and pass, without getting hooked by distracting thoughts of resentment. Most adults I work with live with a mixed bag; some emotions are well tolerated, others are continually rejected.

Alas, when emotions are suppressed they don’t go quietly away; they sit in the body, tucked in tight stomachs or contracted shoulders, waiting for the first opportunity express themselves. If we suppress our anger at work, it will find a way to express itself at home, in outbursts against startled loved ones.

Yet many of us try to feel good all the time, which results in desperate measures to avoid any emotional discomfort.

At first, we may choose unskillful strategies, such as drugs or alcohol, to alter our emotional states. When these fail, we may find ourselves turning to far more skillful strategies, such as yoga, meditation, fasting and so on.

In other words, we may seek escapes routes, or spiritual bypasses, from our emotions, and mistake the initial elation as a form of psychic health.

As a meditation teacher, I’d be thrilled if I could claim, with a straight face, that any spiritual practice will lead to a life without frustration, sadness or disappointment.

What I can claim is that spiritual practice will lead to a state where we can hold our difficult emotions.

Using spiritual endeavor as an attempt to bypass emotions is simply an escapist, avoidance tendency, like workaholism, rumination, indulging in the utopian day dreams. While attending one of my meditation classes may be more palatable than slamming back a few drinks to cope with agitation and stress, all forms of bypass have the same ultimate goal, which is to disconnect us from feeling and holding difficult emotions. Essentially, this is avoidance, and as I’ve noted above, it doesn’t work, it just leads to even greater suffering.

There’s nothing healthy about using spiritual practice to escape loneliness, sadness, disappointment, whatever we’re feeling; its actually a form of self-harm to tell ourselves we shouldn’t feel something.

While it’s important to learn to detach from the stories that needlessly trigger depression or blame, we must learn to open to the sadness or grief that seeks our attention.

My process of sitting with difficult emotions is straightforward:

After sitting quietly for awhile, relaxing my breath and releasing my body from the momentum of busyness, I bring to mind a difficult experience—perhaps an unpleasant interaction that has occurred—and hold a static image of the event in the “movie screen” of my mind (the area where I visualize memories).

Then I ask a few questions: “How does it feel?” If nothing arises, I may have to prod a little: “How does it feel to be unheard/mistreated?” Then I observe as the physical expressions of anger or fear arise in the body. It’s essential to not repeat the “How dare they!” stories, which are simply distractions from the real, physical expression of emotions.

Eventually, attending to difficult emotions isn’t as painful as it may seem; emotions are only monstrous when they’re not welcomed.

And, note that liberation is not a state without emotion; it’s a state where emotions and sensations can be held and tolerated without adding needless thoughts, which only create reactivity or suffering.

So, spiritual growth should not be seen as the achievement of lasting elation or those “everything is beautiful” tones of voices one hears at some spiritual centers. Being a spiritual practitioner means being available to whatever is present, no matter what the sensations and energies are present, without anything defining us.

It’s not really about being above it all; it’s about being with it all.

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

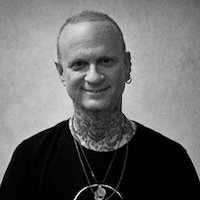

Author: Josh Korda

Editor: Emily Bartran

Photo: Francisca Ulloa/Flickr

Read 6 comments and reply