I recently saw a social media post of a person proclaiming that “This is the real meaning of yoga.”

This individual cited an article that discussed how yoga is all about a specific sutra in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. This one statement, albeit completely innocent, is both a root in the beauty of yoga diversity and a root in the problems that can arise in yoga communities.

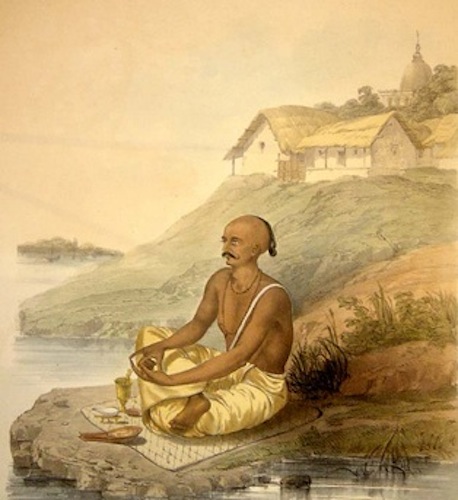

Some people might say that the real meaning of yoga is in the Bhagavad Gita, an ancient chapter of the epic Mahabharata that expresses yogic ideals. On the other hand, what about a person who embodies the 8 Limbs of Yoga, and goes so far as to actually live the life of a Brahmacharya? (1)

Other people might say that the real meaning of yoga is to teach people how to relax, but in turn make enough money to sustain a business and the lives of the people who keep the business afloat. Others say that the meaning of yoga is to master handstand, and then refuse to practice under any instructor who cannot do one, despite the fact that there are so many styles of yoga and methods of teaching and practicing.

Guess what? All of these “meanings of yoga” are correct. And the coolest part is that you are likely to meet a person who shares your belief in what yoga is and what it is not. However, that person is likely to also disagree with some of your beliefs about “real” yoga.

For many readers, I am likely preaching to the choir. However, how many of us have witnessed conflict in yoga communities, or gossip, or any type of slander over simple assumptions about what yoga is, what yoga is not, and who is a “real” instructor?

I am not here to offer a remedy—but I do want to discuss how cultural anthropology might ask the same question: “What is the real meaning of yoga?”

A main tenet of anthropology is cultural relativism, which is the act of examining a culture in its own right without imposing one’s own views of right or wrong. Taking a culturally relativistic perspective does not mean that we have to agree with everything another culture practices or believes. In the case of yoga, a widely diverse practice, it can be helpful to take a culturally relativistic perspective when recognizing differences among groups of practitioners.

Different styles of yoga “value” different things. For example, yin yoga practitioners might value a deep stress in the connective tissues, whereas a hot power student might highly value a cardio workout. Just because a style is not your preference, does not mean that the style of yoga is inauthentic, or missing the point of “real” yoga.

Anthropologists also rely on cultural models to explain a “thing” of interest. For example, the “thing” could be a religious ritual surrounding the death of a loved one. Death rituals are a behavior shared by all humans, but the ritual display varies across cultures (check out this Taboo episode).

Once while I was in India conducting research, I saw numerous parades where dead corpses were carried through the street on a brightly decorated float. Passerby would set off fireworks, play drums, sing, and chant. From my American perspective, I thought this death ritual looked incredibly close to annual Fourth of July parades in my hometown, but instead, people were mourning (or possibly celebrating) the passing of life.

When there are a lot of people who engage in a specific behavior, there is bound to be a lot of variation in the beliefs surrounding it.

The variation in the beliefs does not detract from the “original” meaning or purpose of the behavior (whatever that is, anyway) because behavior evolves over time and can take on new meanings. Furthermore, the variation could be due to numerous factors such as cultural differences (e.g. American Christians who practice Christian yoga), or the environment (e.g. access to certain resources, such as a lovely beach for Boga).

So, next time we read an article about the “meaning of yoga,” or hear similar chatter in a studio, we need to remember that these ideas are part of a bigger cultural model (or maybe they are one person’s idiosyncratic beliefs) that may not be shared by all, but are no less valid or meaningful for the people (or person) who share the meaning.

**

Note:

1 A Brahmacharya is traditionally viewed as a person who renounces sex, although even the definition for this term is up for debate. B.K.S. Iyengar said that you can be married and be a Brahmacharya if you exercise control over your desires. (Iyengar, B. K. S. (1979). Light on yoga. New York: Schocken Books.)

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

Author: Caity Placek

Editor: Renée Picard

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply