“Neurosis is always a substitute for legitimate suffering.”

~ Carl Jung

If two things could sum up modern society and culture they surely are neurosis and suffering. The principle of (suffering) is one of the most important concepts in the Buddhist tradition.

The Buddha is reputed to have said: “I have taught one thing and one thing only, dukkha and the cessation of dukkha.”

But how are these two concepts related and what can we do about it? In Buddhist teachings there are three basic levels of suffering:

- Dukkha-dukkha (ordinary suffering)—the obvious physical and mental suffering associated with birth, growing old, illness, and dying.

- Vipariṇāma-dukkha (produced by change)—the anxiety or stress of trying to hold onto things that are constantly changing.

- Saṃkhāra-dukkha (meaninglessness)—a basic unsatisfactory sense pervading all forms of existence, because all forms of life are changing, impermanent and without any inner core or substance. It is what the French call “ennui” or Germans call “existential angst.”

There are two aspects of suffering that bear consideration.

The first is that suffering generally involves feeling pain or distress and the second is that it means to experience or to allow something into our consciousness or senses.

We are familiar with the phrase: “no pain, no gain.”

All growth involves some level of distress and discomfort. We seem to swim in a sea of change, pulled by the tides and tossed by raging tsunamis.

Our senses, which include our conscious mind, are designed to alert us to harm and generally we pay more attention to threat than to pleasure.

To our conscious minds, suffering and anxiety seem to be unending.

But if we sit quietly and observe, we find that our suffering comes and goes, running through our lives more like a brook or stream than a biblical flood. We only drown in our suffering when we dam up or disallow life’s free flow and become attached or identified with our pain.

Philosopher-inventor Buckminster Fuller once stated: “I am a verb.”

Possibly what Jung was calling “legitimate” suffering is this flow of feelings and anxiety that naturally arise as our lives unfurl.

At the core of Buddhism is the concept of “non-attachment.”

If we cling to outmoded thoughts, ideas or concepts, we hamper the flow of life through us. Our attachments pile up, constricting life’s streams and creating stagnant pools of suffering, their levels rising until our very sense of being is submerged. Saṃkhāra-dukkha, a prevailing sense of ennui or dread, fills our consciousness.

Stuck in this swamp of despair, our life has no joy, no meaning. Because we fear to let go and become unattached from our flotsam, we cling tightly to the debris and rot around us.

“People have a hard time letting go of their suffering. Out of a fear of the unknown, they prefer suffering that is familiar.” ~ Thich Nhat Hanh

Sadly, as the saying goes, “When you’re up to your ass in alligators, it is difficult to remember the objective was to drain the swamp.”

There is a process to restore the legitimate flow of life through us again.

It is the grieving process, a natural way to let go, break up the logjam of rotting defenses and wash ourselves clean again. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, a Swiss-American doctor, identified several stages of this mysterious process of resilience and transformation:

- Denial and isolation (shock)

- Bargaining (resistance)

- Anger (reaction)

- Depression (acknowledgement, surrender)

- Acceptance (adaptation, growth)

These stages are arbitrary and often we can get stuck or get caught up in a loop, such as cycling between anger and bargaining, before we can surrender into feeling the depths of our sorrow and depression.

It is also important to realize that we are in a continuous process of grieving and, as Jung points out, it is a constant imperative in order to give hope and meaning to life’s cycles of death, reconciliation and rebirth. Grief is a natural, subconscious process that wears away the debris of our shattered ego and allows life to flow freely through us again.

It is not just physical death that awakens this transformative process within us, but the everyday changes and challenges we experience such as a divorce or end of a relationship, loss of a career, security, trust, health, youth or even a dream. These symbolic “deaths” are often not acknowledged and are denied due to shame and our fears of rejection, but a backlog of unprocessed grief can lead to compound grief when a major tragic event unleashes a tsunami of sorrow and suffering.

Let the tears flow.

Let life’s sorrows and suffering move us deeply and free us from outmoded ideas, hopes and dreams and awaken us to the integrity of the moment allowing us the experience of the exhilaration of our spirit cascading through us.

Become the verb, as “Bucky” describes, and go effortlessly with the flow, letting life’s sufferings wash through you, because to do otherwise will only drive us crazy, and those around us as well.

Life is wet—go ahead and dive in.

~

Relephant read:

The Value of Holding Space with Another’s Grief.

Author: John Hardman

Editor: Ashleigh Hitchcock

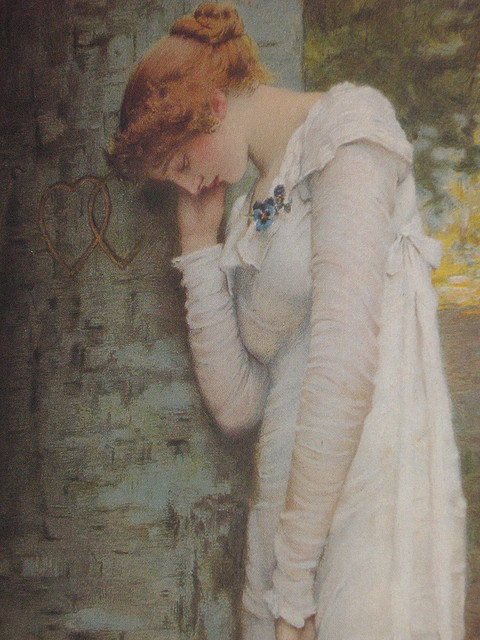

Photo: flickr

Read 4 comments and reply