When I tell other parents that I drive an hour each way to take my son, Henry, to school, most think I’m crazy.

But most don’t have a child with a learning disability. If they did, they would realize that an hour drive is a small price to pay to watch a child whose self-esteem was in tatters, not only thrive emotionally but also excel academically.

Most people—educators included—don’t grasp what it means to have a learning disability.

Henry’s third grade teacher certainly didn’t. She was quick to tell me that my son was lazy and disengaged.

“He always puts his head down on his desk,” she complained. And when he wasn’t offending her this way, she criticized him for the opposite behavior. “He’s always getting up from his chair or wriggling in his seat.”

By the middle of third grade, Henry was really struggling. My once happy-go-lucky-son was going to crash and burn. So, I stopped waiting for someone to tell me my son was dyslexic. It seemed as if the educators, I was relying on for help, knew less than I did.

Instead I dialed up the Charles Armstrong School in Belmont, California, an independent school that specializes in remediating kids with dyslexia.

I sent them all the public school’s test results, qualifying Henry for his Individualized Education Program (IEP). But they also requested Henry sit for a Slingerland Screening, a test that looks specifically for dyslexia. They quickly confirmed what we already suspected.

Henry started at Charles Armstrong the following Fall and it was like entering an alternative universe. I met dozens of families with kids just like Henry—brilliant orators and deep thinkers who struggle with rudimentary academic skills, like reading, writing and spelling.

The school’s research-backed teaching methods coupled with a willingness to use appropriate assistive technologies in the classroom worked wonders.

The educators at Henry’s new school were also the first to suggest that perhaps Henry also had ADHD. We’d, of course, discussed Henry’s fidgetiness at the public school, but only as it pertained to being disruptive to the rest of the class.

I expected another lecture on how I had to get Henry to settle down. “We don’t stop it here, explained the counselor. We encourage it.” Kids that have ADHD aren’t over-stimulated. They’re under-stimulated. They seek out additional stimulation to help them concentrate

When I told them that I’d been forcing Henry to complete his homework in a distraction free environment, they encouraged me to reverse course. “Let him listen to his iPod, if that’s what her prefers,” the counselor suggested. And if he preferred to stand while working at school, well, that was fine with them. The quality of his work increased dramatically.

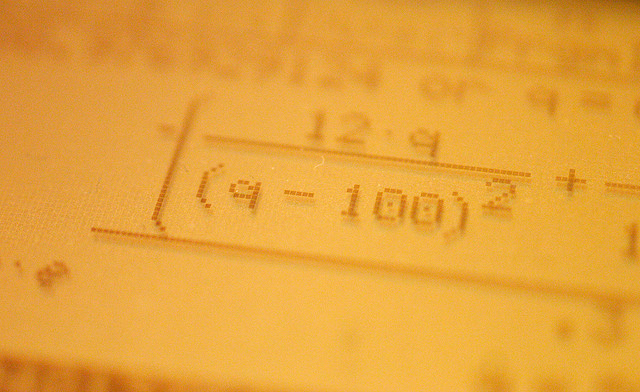

The only area where Henry continued to struggle was in math. He understood the concepts, they were teaching, but his handwriting was so bad, that even he has trouble reading it. As for creating number columns, neat enough to effectively add, subtract, multiply or divide multiple-digit equations, well forget it.

We learned from the teachers, at Henry’s new school, that there’s actually a clinical name for really crappy handwriting. It’s called dysgraphia and it commonly co-occurs with dyslexia and/or ADHD. For written assignments, they immediately got him on a keyboard. But with math that simply wasn’t an option.

I scoured the internet looking for an assistive-technology to help him around this next obstacle, but came up empty.

When I voiced my frustration to my husband, he said: “Why don’t we just make one?” It seemed crazy at first. But, hey, everyone and their mother seems to have an idea for an app, so why not us. Plus, we figured there must be 1000s of kids like Henry, who could also use the app.

It was a stretch for us financially, but giving up was not an option. So, we hired a coder and designed an app, which Henry dubbed ModMath. It uses the touch screen and an on-screen keypad so kids can set up and solve math problems without ever using pencil and paper. Assignments are laid out on virtual graph paper that can be printed or e-mailed to the teacher.

Since its debut in the App store, 14 months ago, it’s helped Henry and more than 27,000 dysgraphic kids around their disability. We decided not to charge for our app, because kids with learning disabilities have enough challenges, we didn’t want cost to be another. We tapped out our personal finances on the beta version so a Kickstarter campaign has now been launched to raise money for the many upgrades our users have requested.

I know there will be additional bumps along this journey. But I am thankful every day for my grueling commute. I shudder to think where we’d be today if we’d left Henry at our local public school, which was woefully ill-equipped to teach children with learning disabilities.

In addition to providing Henry with a superior education, his new teachers instill in him a belief that he can succeed despite his dyslexia.

Academic struggles colored the childhoods of many famous dyslexics, including Charles Schwab, Richard Branson and Steven Spielberg.

But, on the flip side, their disabilities instilled grit, perspective and the kind of out-of-the-box thinking that separates the good from the great.

~

Facebook is in talks with major corporate media about pulling their content into FB, leaving other sites to wither or pay up if we want to connect with you, our readers. Want to stay connected before the curtain drops? Get our curated, quality newsletters.

*Relephant read:

Parenting: The Hero’s Journey.

~

Author: Dawn Denberg

Apprentice Editor: Renee Jahnke/ Editor: Ashleigh Hitchcock

Image: Tom Page-Flickr

Read 0 comments and reply