I don’t remember who broke the news, whether it was my brother or my mother or even a relative.

I remember only saying the words aloud to my roommate after hanging up.

“My dad is dead.”

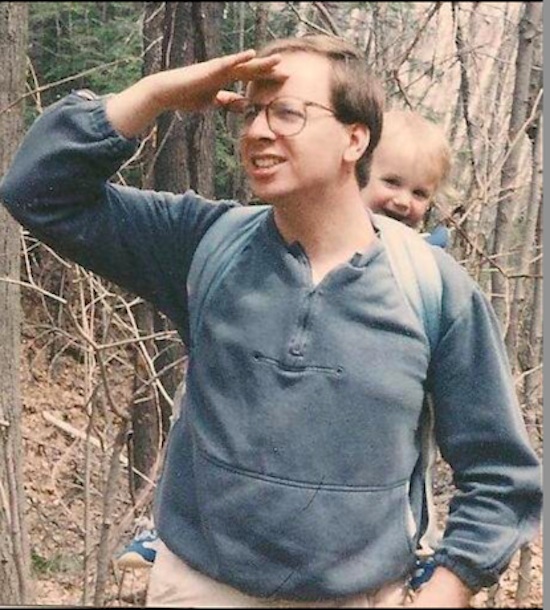

It was November. I had just turned 24. I had begun graduate school in September and had spent the last moments of his life writing reports alongside his hospice bed. I recall teachers telling me to take time off, encouraging me to turn in assignments late. They were psychology professors after all; they well understood the implications of this event. But the work gave me a purpose and some semblance of normalcy in a world—my world—that in the last 9 months had been dismantled. I punched away at the keys of my computer the last two weeks of his life, as stomach cancer, now spread to the liver, stormed the enemy lines of vitality. Occasionally I would glance over, hoping to meet his morphine clouded gaze. My dad died only 9 months after diagnosis. He was 54.

I met my sister at an Upper West Side Mexican restaurant soon after receiving the news; an experience I wouldn’t remember at all had it not been for the mariachi band plucking away and singing gleefully beside our table. We laughed and cried through the irony. Our dad was gone.

Flash-forward to five and a half years later. I sit in my Brooklyn apartment as I approach the age of 30 and wonder what I’ve learned these years without my dad. In many ways I feel losing my dad is an experience on a shelf somewhere that confronts me only sometimes. But I know deep down not having my dad is with me every day. It bikes with me to work as I gingerly watch out for wayward vehicles. It’s stored in my phone under 19 doctors’ names and numbers. It’s perched on my shoulder as I watch dads walk daughters down aisles. It’s rooted within the fraught relationship with my mom. It sits in the pit of my stomach on first dates and stands guard during breakups.

More recently, bereavement is being viewed as an indefinite process, not confined to set of stages or rigid timeline, not something you overcome and then wrap neatly in a box and place under a bed or up on a shelf. Grief is personal, subjective, sometimes flaring, sometimes flickering.

The last five and a half years I have not overcome the loss of my father so much as I’ve learned to coexist with what’s missing. I’ve grown accustomed to the changed family dynamics, the pathologies that stir. I have become aware, thanks to therapy, that I may need to work a little harder on myself, because losing your dad in your 20s is not any less significant than facing the loss as a child. I was 24, but I was someone’s child.

Grief has also given me this: ever closeness with my siblings, the ability to identify with colleagues much older than myself, the empathy I feel when, as a school psychologist, I learn a student is grieving. There’s the shared feeling of injustice in learning a friend has also lost her dad, for grief has connected us in a way only we understand. Yet, I am not an outlier; I have experienced what most people will, at some point in their lives, experience. At 24 I was catapulted and rendered wise beyond my years; at 29, I am still finding my footing.

The sun has just set and the mosquitoes are in search of an evening meal. I am 5-years old. It’s a sticky July night. I am seated on my bike, a familiar posture, only this time without the support of training wheels. My dad, for the last hour, has been jogging back and forth with me as I pedal, clutching the back of my seat.

“Okay we’ll practice one more time,” he says breathlessly, “then it’s time to go inside.”

“Okay but still hold on,” I plead.

I brace myself and begin to pedal. I pedal faster, my heart racing as the the warm breeze tosses wisps of hair across my face. I approach the driveway and push the pedals back, the tires squeal lightly. Releasing one foot to the ground, I look over my left shoulder. He isn’t there. Holding onto my handlebars I hop off my bike and turn around. I see him standing back where I’d started, a huge grin on his face. Forgetting gravity I let my bike fall and sprint toward his outstretched arms. My dad knew, before I knew, that I could pedal on my own.

~

Author: Lauren Ross

Editor: Alli Sarazen

Photo: Courtesy of Author

Read 7 comments and reply