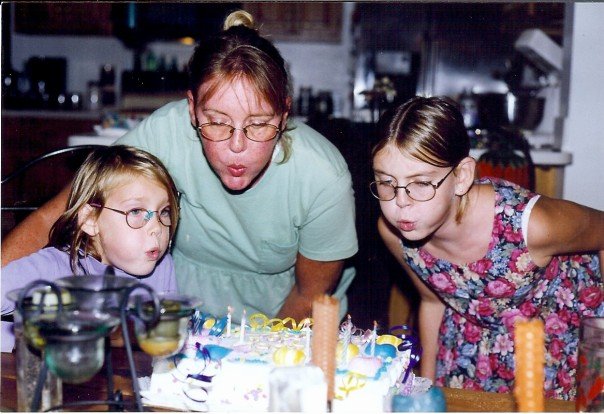

*This article is dedicated to myself on my birthday, and my mom who gave me a birthday to celebrate.

As I approach my 27th birthday at the end of this month, I am giving myself what people often give themselves on or near their birthdays: introspection.

This year has been a hell of a year—far beyond what I thought I would ever go through—and has been unique in two major ways: the first is that around this time last year, my mom passed away in California, which triggered my first life-altering, all-consuming grief. The second is that a month later, my boyfriend and I opened a yoga studio in Chicago, which has been a challenging mix of moving pieces.

Because grief and business are brand-new experiences for me, it is sometimes puzzling how my thoughts and feelings relate to each other—I’ve worked on fliers at the yoga studio, crying and confused because I don’t know why I’m crying. I’ve rolled over at 3:00 a.m. and wondered if I can’t sleep because of my mom or the studio, and usually decide it’s a little of each.

My year has been a back-and-forth seesaw of mental activity, with my attention vacillating constantly between what was and what will be: my grief orients me towards my past, and our year-old business faces me towards the future.

As a birthday present to myself this year, I have sat down nearly everyday for an entire month to write this article. I’ve found myself contemplating all sorts of things, and what has come out of it is the story of my suffering, which I’m realizing is not my story at all.

It’s our story.

For anyone who has been plagued by the past or future, or who has been confused by thoughts and feelings, or has wondered if suffering ever goes away: this story is for you.

1) The Past as Grief

We were both suspecting and not-suspecting that my mom was going to die. It would have made sense for her to die on any day of the last 17-years, which is when her autoimmune disease started.

While she spent most of her time in bed trying to manage the pain of a seemingly stuck, un-changing moment, my sister and I underwent so many changes: I was eight and Avry was five when her illness started, and when we got the call that she had passed, I was 25 and my sister 22.

She was alive during our childhood lives of friendships united, friendships destroyed, passions followed, passions denied. She was there during the development of all our decision-making strategies that determine seemingly high-stakes events like college, relationships, careers, happiness, life!

Growing up, there was a shared household belief that illness is a thief of happiness, and a family-wide cessation of our own happiness to cope with the unyielding, unbending misery that overcame her.

Whether there was love between us was never a question—there is only love and always love. The questions arise when I ask myself, “was I happy?”

My grief begins with this question, as I end my 25-year relationship with my mom. The process of looking back or closing a relationship contains a lot of memories, and this is primarily what my grief is made of.

The memories stack on each other, so that when I recall an event, it is not just the moment of the event happening that I recall, but every other subsequent time I have recalled that same event, and the analysis I have drawn from those remembrances.

For instance, let’s say I’m sitting at lunch working on an email for the studio.

As I type away on my computer, I am flooded with memories of myself growing up, with my mom, with other family members. To the outsider, I’m just doing something on a computer, but internally there are 40 Brentans tumbling past each other, all made by memory, each one a complete and different picture of myself from various periods throughout my life. Some of these Brentans feel close to me, some feel very far away. Some Brentans I judge, curse, or throw a book of “should”s at.

With 40 versions of myself floating around, each receiving my attention for a moment until the next memory files in, I stumble frequently, always, and absolutely to the question: who am I?

It appears that I have mistakenly believed myself to be these Brentans in different moments throughout my life, but this person is actually just a mental character that is made and re-made in memory or fantasy, but never reveals itself right here and now.

Returning to the example of email-writing at lunch—at this point, I’m doing less email-writing than sitting and staring. I lose touch with the chair I’m sitting in, the room around me, the sensory potential to feel plugged-in to one’s environment. I become logged in thought, which takes me through small emotional experiences of sadness, anger, pity, inadequacy, defeat. (These are the contents of my grief.)

Suddenly, three hours go by, and perhaps I have completed several tasks—driven a car, washed some dishes, cooked another meal—but I have blurred my ability to pay attention to the present moment, which I experientially understand to be the only moment that actually exists.

This is how my past makes itself relevant in the present. These are old beliefs that I am the same person I was yesterday, and that I have the same false, self-imposed limitations from yesterday.

The past shows up in our lives in all types of forms, but at some point, it will show up to everyone as grief.

Grief is one of the few emotional experiences that is inarguable. There is no sending grief away, opting out of it, or asking it to come back later. It exposes our coping mechanisms as lies we uphold in order to look in the mirror and say, “I’m fine”. It cannot be dulled with Netflix, shopping, or going towards any other object. It is here to be felt right now.

A year into grieving, I am starting to see the ways in which it is self-generated and the ways in which it is self-relieving. The relief comes when grief is allowed. When I feel my pain, I have the opportunity to study how I suffer, to get to know how I work on the inside, what types of thoughts lodge themselves into the deep, muddy part of the mind.

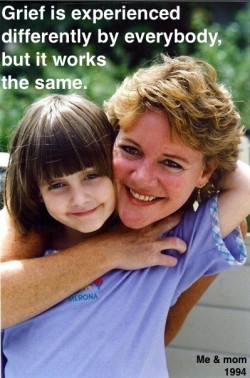

Grief is experienced differently by everybody, but it works the same: experiencing pain makes us interested in knowing peace. The interest is important, because in order to experience peace, there must be interest—a willingness to discover where it isn’t, so that we may find where it is.

2) The Future as Worry

It turns out, there’s no adequate preparation for starting a business besides actually doing it. Once it begins, all mental energies shift toward thinking about its well being, with any residues of self-doubt awakening and resurfacing as worry.

This is something I imagine all of us to feel at various points throughout our lives. Perhaps we are accustomed to calling it different things—but at some point, when we take on adventures that are so wholly new and unpaved, we will feel anxiety, doubt, fear, worry…

My sense of worry began a few days after we opened, sitting on a stack of yoga blankets at the yoga studio for the second no-show class in a row. With an empty studio and a thousand futures laid out before me, my own worry set in, and has, since then, underscored most of my days.

When it comes to business, money seems to be the biggest worry. Perhaps this is because of the dualistic nature of the system: either we have a yoga studio, or we don’t; people come, or they won’t; we make money or we go out of business. There is no in-between. These all-or-nothing scenarios tease me with success and failure, every scenario involving the hunt for money, underpinning my sense of worry.

This worry expresses itself in a few aspects of my job, especially the parts that I don’t like.

For example, I didn’t know before we opened the yoga studio that advertising is something I really don’t like to do. For me, advertising seems similar to how I learned to put on makeup and wear clothes “for my body type” when I was a teenager—it’s a lie used to “control” how other people perceive me.

But to opt out of advertising means to opt out of business, as both are products of the system, which is designed to make people believe that it’s possible to buy our way out of suffering. (I sometimes wonder if I must also adopt the same money-idolizing values of the system in order to “succeed”.)

This type of thinking has been standard for me this past year, and is a direct pathway to worry.

The way grief will drum up 40 different Brentans from the past, worry invents 40 Brentans of the future—all undertaking completely different lives and hardships. Some of these Brentans have gone broke, others have been hugely prosperous, still others have jumbled lives of success, failure and confusion. These Brentans spin around each other, each expressing a variation of fear or hope (which eventually shows itself to be fear as well), as if in a tumble-dryer set on spaz and labeled “Lies About the Future.”

The more I get to know this worry, the more is resolves itself, and a year into owning the studio, I’m starting to experience a decline in these feelings.

For most of the year, I’ve tried to fight my worry, not understanding that suffering can only be defeated when surrendered to. To surrender means seeing where it comes from, how it arises, what places it tickles and pokes inside. It means finding every thought put out of the mind, every feeling left unresolved. And although it hurts like hell, the victory is that it resolves itself, because the suffering that is allowed in must also be allowed out.

Growing up, I’ve believed that only some people go through hard times, or some have more hardship than others, or that a lucky few are spared from suffering altogether. But as I’ve experienced my suffering this year, I’m seeing that this isn’t true at all—that suffering is actually equal from person to person; and while it reveals itself to everybody as different circumstances, our experience of it is the same.

The contemplation of this year has boiled down to 14,000 words, 2,000 of which have made their way into this article. I have written about all kinds of things in the quest to understand my suffering.

To my business, I say thank you.

To you, I say the following: I offer you not my personality, my likes or dislikes, my persuasions and opinions, or my affiliations of any kind. I offer you an observation of what it means to be alive, from the place that is alive in me, to the place that is alive in you. Thank you for the opportunity to share a story that belongs to all of us.

Namaste.

Watch or listen to article read by author:

Read more from Brentan:

Can We Be Lovers & Not Have Sex?

Relationships: Why We Cheat.

Author: Brentan Schellenbach

Editor: Renée P.

Images: via the author

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply