It’s Wednesday afternoon in Brookline, Massachusetts, and I’m sitting down among a group of Patricia Walden’s senior Iyengar students, talking about literature.

Not just any literature, of course, but specifically those books that have influenced and informed our practice of yoga.

As we go around the room, each of us offers up a short list of our personal favorites, including The Upanishads, the Yoga Sutras, and The Bhagavad Gita. Some students have also read the more esoteric Hatha Yoga Pradipika, or Buddhist classics like The Heart Sutra.

Still others have eschewed literature entirely, in favor of the direct knowledge that practice brings.

“My impression is that when most people talk about yoga, they are talking about asana,” Walden points out. “They aren’t doing much pranyama or svadyaya, self-study.”

While acknowledging that asana practice is a primary tool of self-discovery, Walden emphasizes that the study of classic texts like The Yoga Sutras and The Bhagavad Gita can also be extremely important to one’s practice, because they help shed light on some of the profound concepts that lie at the heart of yoga—particularly during difficult times in our lives.

Last fall, the Iyengar discussion group took on the Bhagavad Gita, along with the Katha Upanishad, as a way to understand and process the passing of their guru, B.K.S Iyengar during the summer of 2014.

Both texts deal with the inevitability of death and the yogic approach to human mortality.

Iyengar himself was a prolific writer, composing such classics as Light on Yoga, Light on Pranyama, and Light on the Yoga Sutras, the latter of which I first came across while taking classes the Harvard Divinity School in a two-year academic quest to read as much as I could about the intellectual and historical roots of the practice I had come to love.

What I discovered, of course, is that the study of yoga and its important texts (like asana itself) is really a lifelong study—reading and re-reading the often crystalized aphorisms that can defy our understanding the first time around.

After all, what does it really mean when Patanjali says: “Yoga is the cessation of the fluctuations of the mind (Yoga citta vritti nirodhaha)”?

Does it mean that you are brain dead when you achieve enlightenment?

One of the best Iyengar quotes that the master himself passed along on the subject of death is that he practiced not so that he could learn how to die while he was still alive, but to learn how to live better before he died.

We could talk more about nirodhaha, but let’s move on.

Hindu narratives, known as the puranas, are perhaps the most accessible to a householder yogi, for the appeal of a good story makes its message easier to remember, if not easier to digest.

What is it about a good story that captures our attention? Certainly the drama of a good narrative can often resonate with the experience of our own lives, although it may be a bit more exotic or exaggerated, filled with characters who are familiar enough to relate to but odd enough to make them worth trying to figure out.

Hindu mythology offers us some of the most wonderful and complex characters ever created in humankind, delighting and challenging the reader to try and understand the multiplicity and sophistication of the philosophical concepts that emerged from the Indian sub-continent.

As yoga teachers and students, it can be useful to understand at least a little bit about the culture from which yoga emerged, for it can bring us into a deeper relationship with the inner practice within the context of external form, regardless of our own religious and cultural beliefs.

When you are in anandadsana, for example, and conjure up the image of Vishnu sleeping on his side, floating on the serpent cushion adi sesha and the waters of creation until Brahma grows out of his belly and begins the next cycle of the world, it can evoke a wonderful multiplicity of images and the concept non-linear time.

Or, if you are struggling in hanumanasana, you might gain courage and sakti to remember selfless monkey god in the Ramayana, leaping across the ocean between India and Sri Lanka to help rescue the Princess Sita!

Lastly, if you are in sitting down deep into a warrior pose and recall the story of Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita, you might be able to embody the challenge of acting boldly and skillfully by connecting your practice to something larger than yourself.

These are but a few playful examples, but yoga texts can take us deeper.

During a class I took on the Bhagavad Gita, a Harvard professor once encouraged me to read and re-read the story of Arjuna and Krishna as much as I could tolerate, by using different translations.

“Let the narrative start to exist within you,” he suggested, implying that the wisdom of the text only reveals itself to the worthy, by eventually melting into one’s subconscious.

Perhaps when a story becomes internalized, it begins to exist in a different way—as something that we can actually feel a part of and apply to our current lives.

On this deeper level, I have definitely found that reading yoga narratives (and other texts) can bring my mind to a state of calm understanding in a way that is quite similar to meditation.

Could this be a form of nirodhaha, too?

You’ll have to answer that question yourselves—so dig in, fellow yogis and yoginis, and pick up a book every once and awhile!

~

Relephant:

How Old is Yoga Asana?

~

Author: Dan Boyne

Editor: Caroline Beaton

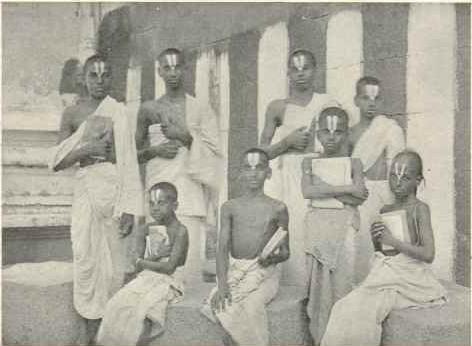

Photo: Google images for reuse

Ready to join?

Hey, thanks so much for reading! Elephant offers 1 article every month for free.

If you want more, grab a subscription for unlimited reads for $5/year (normally, it's $108/year, and the discount ends soon).

And clearly you appreciate mindfulness with a sense of humor and integrity! Why not join the Elephant community, become an Elephriend?

Your investment will help Elephant Journal invest in our editors and writers who promote your values to create the change you want to see in your world!

Already have an account? Log in.

Ready to join?

Hey, thanks so much for reading! Elephant offers 1 article every month for free.

If you want more, grab a subscription for unlimited reads for $5/year (normally, it's $108/year, and the discount ends soon).

And clearly you appreciate mindfulness with a sense of humor and integrity! Why not join the Elephant community, become an Elephriend?

Your investment will help Elephant Journal invest in our editors and writers who promote your values to create the change you want to see in your world!

Already have an account? Log in.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply