If you take a tour of the web, it’s not at all difficult to find lots of people who are still pissed off at and others who are perplexed by the Vidyadhara, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

His behavior—his consumption of alcohol in large quantities and his consorting with who knows how many women—was not what is expected of a holy person and, some 30 years after his passing into nirvana or his death (depending on what view one takes of him), he still seems to be quite disruptive and upsetting.

The difficulty that people have, as far as I can tell—and it is a very serious difficulty—is this: If a teacher is not enlightened, then alcohol dependence and sex with students is just ordinary confusion, hurtful to themselves and to others, and that “teacher” should be avoided. However, if the teacher is enlightened, then everything he or she does is reflective of that enlightenment—and everything means everything.

There is no middle ground, much as we would like there to be; otherwise the founding Kagyu sage, Tilopa, must be regarded as an extraordinary sadist in his treatment of his student, Naropa. Naropa’s student, Marpa Lotsawa, must be regarded as a somewhat more ordinary sadist in his treatment of his student Milarepa, and Drukpa Kunley, the Mad Yogi of Bhutan, must simply be regarded as a drunk and exploitative philanderer.

And what of the mahasiddha Virupa who hung out in bars and brothels?

And, for that matter, what of Guru Rinpoche who had more than one consort and, worse, killed a child?

How do you tell the enlightened from the unenlightened teacher? That, of course, is where we all run into problems. It took me about 11 years to make up my mind about Trungpa Rinpoche. The drinking never bothered me, but his sexual behavior did.

I had the good fortune to be in a group interview with His Holiness the 16th Karmapa way back when and I asked him about my doubts. Basically, he just laughed at me and as we all left the room and came up one by one to be blessed, he thumped me three times pretty hard on top of my head; I always took that to mean, “Wake up, you idiot!”

It was only after leaving Trungpa Rinpoche’s sangha (I had had some close exposure to the Board of Directors and did not care for them at all either), looking for another teacher and discovering that no other teacher “spoke” to me the way Rinpoche did that I started to surrender. I realized that it was not a matter of choice, that there was a karmic connection that I could not avoid.

I also decided that what anyone else did or thought or how they behaved was not my problem: the only issue for me was what happened when I sat down on the meditation cushion; that was real, or at least as real as anything could be. Once I realized that, I also realized that any genuine practice of the vajrayana would require that I accept the teacher completely, not picking and choosing the parts I liked and didn’t like or approve of. I’m still struggling with that, though perhaps less than I used to.

Another key moment was one evening when I was at Rinpoche’s house at Karmê-Chöling, cooking dinner for Rinpoche and his family. Everyone was in the kitchen, Rinpoche, Lady Diana, Gesar and Ashoka and I was at a counter working; then, suddenly I realized that everyone had left except Rinpoche. He was sitting in a chair with his back to me, just sitting there doing nothing. All I saw was the back of his head, and that’s my memory, just glossy black hair. I was far too shy to talk to him, but I was thinking furiously, asking myself, “Is this really my guru? Shouldn’t I be experiencing something unusual? Am I experiencing something unusual? True, I feel an intense awareness, but wouldn’t I feel that if Ronald Reagan (then President of the U.S.) were sitting there? This is really nothing special.”

Dinner was served and eaten and I went back to Karmê-Chöling where a good friend of mine, who was one of the first—and fervently devoted—students of Rinpoche’s, greeted me and asked me eagerly, “How did it go? How did it go?” I was going on about how ordinary the whole thing had been when she started laughing at me quite hard. I asked her what was so funny and she asked me, “Do you have any idea how the energy is just pouring off you?” And then suddenly I did realize it. It was so odd, it took someone who was not me to make me aware of what I was experiencing, an energy unique in my experience. And that was when I fully accepted that Rinpoche was inescapably my teacher.

Two things about Rinpoche that I think that I can say with confidence: First, he never marketed the dharma or himself. The dharma was truth, not to be compromised for the purpose of pulling anybody in. And if you wanted in, you could come in; if you wanted out, you could leave. No problem, either way. More than once someone would get up angrily during the question period after a talk and rant about how this was a bunch of self-indulgent b.s. and he or she was leaving. And Rinpoche would just say cheerily, “Good bye! Drive carefully.”

The other thing is that he was committed to (and very skilled at) making his students uncomfortable. If you were looking for a guru who would make everything okay and make you feel safe and comfortable in the conviction that you were on the right path and doing the right thing, well, you’d come to the wrong man. He would not allow us to turn him into a prop for our desire to attain a samsaric version of spiritual certainty and comfort—for our spiritual materialism—but, instead, he always threw us back on ourselves as the only place where we would ever discover enlightenment and the real meaning of the guru and devotion.

At my Seminary, he actually said to us, “My job is to make problems; your job is to deal with them.” And since enlightenment requires absolute non-clinging to anything, any kind of guarantee or solid ground, he kept throwing us out of the airplane without a parachute, calling after us, “Good luck! You can do it!”

So he was a master of fruitful disruption, in his life, in his death and ever since. You can read everything he wrote (or spoke) and you will find that he never quite nailed things down, never quite served things up on a platter. Another thing he said that has always stuck in my mind is that a teacher must trust his students more than they trust themselves. So he left space everywhere for us to explore rather than closing off questions with neat answers.

Obviously he is, in a sense, gone and people who never encountered him will have to find their own ways through all the scandalous stories and to whatever conclusions they may reach. I personally am convinced that every single thing he did was an expression of wisdom and compassion. It would really be very, very impossible for me to say how grateful I am to him and how much I love him.

I prostrate before him with as many bodies there are in all possible universes and entreat him to continue his buddha activity as long as there are sentient beings in samsara.

Relephant:

How to Meditate: The Dathun Letter, via ChÖgyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

~

Author: Jonathan Michaels

Editor: Travis May

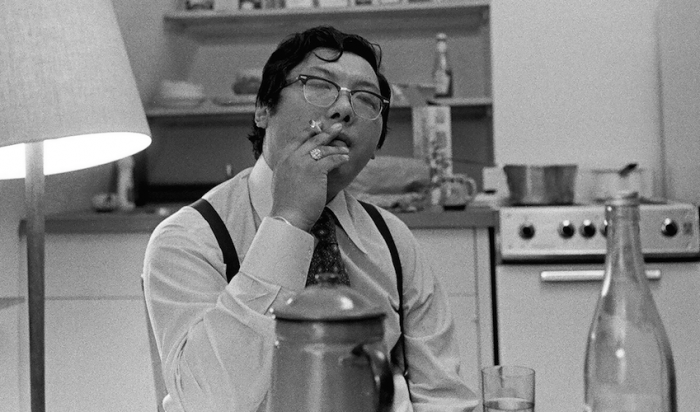

Image: Video Still

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 1 comment and reply