In 2013, a doctor’s appointment changed my life.

After several rounds of routine blood work, I was informed that I had Hemochromatosis, a potentially fatal condition that is classified by an overload of iron.

While normal iron levels are below 400 feretin, I was batting at 1967, a number which I had hoped was a mistake in my results when my disease had been discovered. In a matter of days, I was in the hospital, and the doctors were trying to determine the level of tissue damage I had.

Though I was diagnosed with the hereditary strain, no one in my family had it. I didn’t have the genetic disposition, the diet, or the level of alcoholism that would be required for a person my age to develop it. Hemochromatosis usually manifests in elderly patients, and my advanced case was nothing short of a medical anomaly.

2013 to 2014 was the worst year of my life. My crippling fear of hospitals and needles were made a harsh reality as I underwent phlebotomies on a weekly basis. A nurse informed me that if I hadn’t caught it when I did, I would have died by the age of 29. The emotional, physical and psychological side effects of having to deal with nearly dying were crippling.

And I was angry. I made a list of people I knew who I felt deserved the disease more than I did. I refused to hear stories of triumphing over the odds, finding happiness, and living happily ever after. I didn’t want anything to do with feeling good.

Whenever I read the words, “happiness is a choice,” I cringed. I know that the phrase is meant to inspire positive thinking, but it seemed dishonest to me. Sure, I could have chosen to be happy when I was going through my treatments, but what other emotions would I be covering up? Would my happiness choice take away from the truth: that I was scared, hopeless, and miserable?

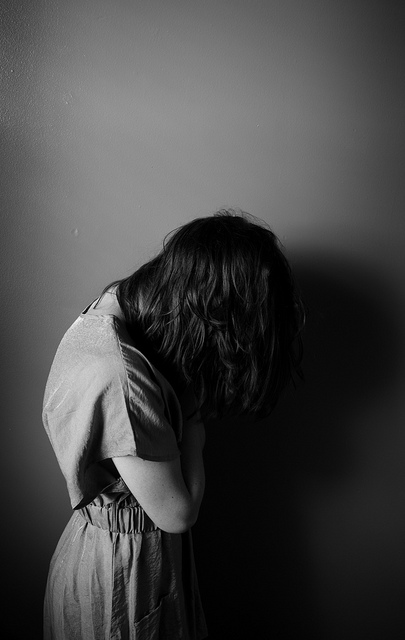

When I was shivering and weak because I had lost so much blood so quickly, I chose to feel sorry for myself. In those moments, I let the feeling of consuming sadness and loss overcome any recommendations from friends and family of “staying positive.”

There were days that I chose to be furious at the people around me in perfect health. After all, I was dealing with something that they couldn’t understand. How could they expect me to be happy when the odds were stacked against me and I was, quite literally, completely alone? I was my hospital’s youngest patient by decades. What did I have to be happy about?

Assuming that the choice to be happy was even emotionally available to me at the time, how could I deny what was really going on? I had every right to be sad. I deserved to honor my true feelings and scream and cry and take as much space as I wanted to. This wasn’t fair, and happiness couldn’t change that. My choice was to wallow, to reach the pit of my despair and make friends with my oblivion. I didn’t want to be happy. I wanted to be me.

And bit by bit, I got better.

I didn’t shy away from despair. I met with him, shook his hand, talked with him, and honored his presence in my life before we parted ways. In retrospect, I’m proud of myself for doing that. I believe that if I hadn’t taken that opportunity, I wouldn’t have made what my doctors called, “a stunning recovery.” I went from being told that I would need treatments once a month for the rest of my life to only twice a year. My old friend despair played an instrumental part in my healing. I am grateful that I did not avoid him.

I’m sure that there are people out there who find that having the happiness choice available to them is a wonderful thing, and that choosing to be happy gives them the motivation to keep going.

Respectfully, I’d like to disagree.

There are times in our lives where we feel like we don’t have a choice and that changing our attitude isn’t like snapping the last puzzle piece in place. And that’s okay. It’s better to respect the depth of the ocean than to fear swimming in it for the rest of your life.

The beautiful irony is that after accepting the existence of my more troublesome emotions, I have become a lot happier. I still have dark days, but my physical and emotional health are back to normal. Without dealing with the honest darkness of my nature, I wouldn’t have been able to appreciate the goodness around me. And I’m happy that I went through all of it.

I don’t choose to be happy. I choose to be real.

Relephant:

F@#! Positive Thinking!

Author: Lauren Messervey

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Photo: Porsche Brosseau/Flickr

Read 1 comment and reply