Have you heard of polyvagal science? If not, you’d better get ready…there will be more and more written about it, especially in mindfulness circles.

Maybe I can have your cherry, arouse your interest in the topic and satisfy your questions.

What the hell does polyvagal mean? It means that our vagus nerve has two branches.

How does the vagus nerve relate to meditation/mindfulness/life? Our vagus nerve is what allows us to experience an intensely active state which has a very different feel than fight or flight. And we don’t access that state simply by deep breathing or relaxing our muscles.

Believe it or not, deep breathing and relaxing our muscles could send us into shut-down.

So, how is this possible?

One branch of the vagus nerve can help us live playful, happy lives. The other branch is responsible for shutting the body down to die. Considering that these are powerfully different functions, how do we make sure we’re moving into playful vagal functioning and not the other shut-down-to-die part?

Stephen Porges is the scientist who created the polyvagal theory based on his research which explored the functioning of the ventral vagal nerve. That’s the playful one. When we use that branch of the vagus nerve, Porges says we are using our social engagement system.

In 2011, Porges published his research in The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, Self-regulation. It’s a very scientific read requiring an ability to glean meaning from words like viscerotropic but Porges speaks about the science in more easily accessible language in person.

Porges chose the term social engagement system because the ventral vagal nerve affects the middle ear, which filters out background noises to make it easier to hear the human voice. It affects facial muscles and thus the ability to make communicative facial expressions. It also affects the larynx and thus vocal tone and vocal patterning, helping humans create sounds that soothe one another.

When mindfulness instructors find soothing vocal tones to cue their suggestions, they are using their ventral vagal nerve biology. And when we hear them, we are using ours.

If the ventral vagal nerve helps us soothe one another, how is it involved with activation?

It regulates activation in such a nuanced way that the activity feels playful.

If you watch dogs in a dog park, you see that sometimes dogs are afraid. Fearful dogs exhibit either fight or flight behaviors. At other times, a dog will signal a wish to play. This signaling often takes the shape that we hijacked for our downward facing dog pose. The down-dog invitation signals an intense level of arousal but the feel of the intensity is playful.

If you’re a real science enthusiast, Lisa Diamond explains the difference between ventral vagal activation shifts and fight/flight activation in The Biobehavioral Legacy of Early Attachment Relationships for Adult Emotional and Interpersonal Functioning, (chapter 5 of Bases of Adult Attachment, 2015).

How do we make sure we’re staying away from the shut-down-to-die part?

The shut-down response is a function of the dorsal branch of the vagus. Shut-down makes death less painful and we want to have it in case we are ever in a life-threatening situation and we can’t fight or flee—we’re trapped.

Can the dorsal vagal nerve shut us down when we just feel trapped—for instance, by a situation at work or an impossible-feeling relationship?

Well, that’s the theory.

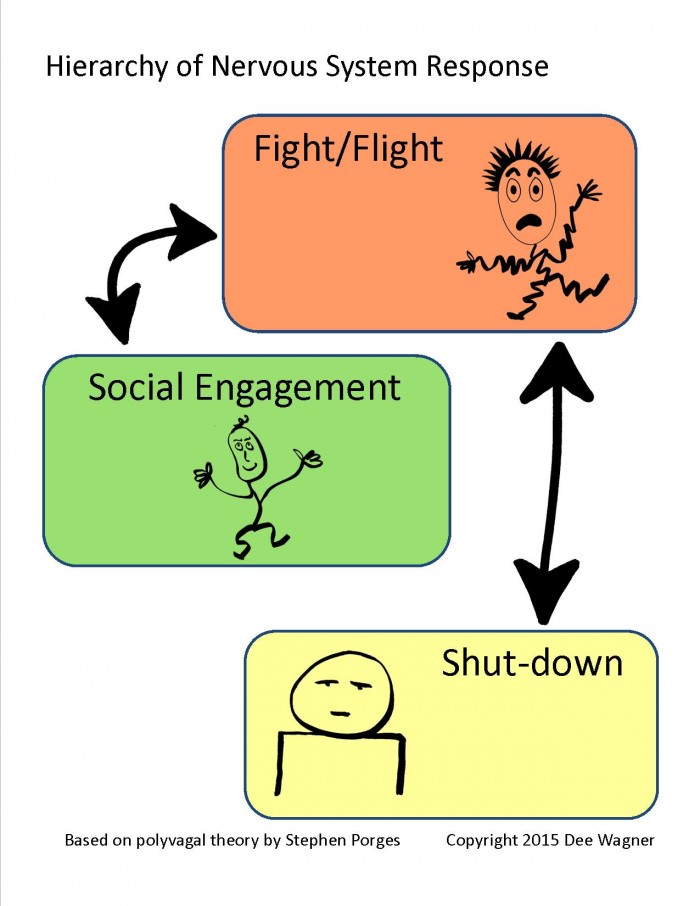

Our social engagement biology requires a sense of safety. When we don’t feel safe, we move first into fight/flight so we can hopefully flee danger or in worst case, fight. If we are trapped, we move into dorsal vagal shut down.

When we feel safe, we don’t need fight/flight or shut-down. The social engagement system can allow active states and soothe through communications that suggest safety.

How can I use this knowledge in my mindfulness practice?

If during meditation practice, we notice our thoughts racing and return to focusing on our breath, we are using our vagal brake. If we drift too far from the present, we are potentially moving into dorsal vagal shut-down. When instructors encourage us to stay attentive to what we feel in our body, they are encouraging ventral vagal calming rather than dorsal vagal shut-down.

We can use our knowledge of polyvagal science to help ourselves do what our instructors suggest.

How can we sense when we are using our social engagement system in day-to-day life?

When we are using our social engagement biology, even if our hearts are beating fast, we have a sense of safety. The active feeling in our body feels playful. Our rest replenishes us.

How do we get back into our social engagement system when we have moved into fight/flight? How do the fearful dogs in the dog park learn to play?

Mindfulness. If we watch our fearful bodily sensations and see that they pass, see that we are actually safe enough, we encourage our social engagement system functioning.

A fearful dog at a dog park can watch the other dogs from a distance. If the behaviors of the other dogs are playfully active rather than vicious, the fearful dog can experiment with joining the interactions.

Can mindfulness shift us into dog-like play, perhaps the downward facing kind, keeping us from feeling we need to shut down?

Yes. That’s what mindful people need to know about polyvagal theory. We have a part of our nervous system that allows a different kind of intense activity that feels more nuanced and playful than fight/flight. When we feel safe enough to activate using our social engagement system, our relaxation can then restore us rather than sending us into oblivion.

Mindfulness helps us to access this system.

Check out an interview on polyvagal theory with Stephen Porges:

Author: Dee Wagner, MS, LPC, BC-DMT

Editor: Renée Picard

Image: via the author

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 2 comments and reply