Tibetan texts on tantric yoga sometimes say that you should see whatever appears to your sense perception as the rainbow light body of the deity that you’re practicing—clean clear in nature, non-substantial, non-dual, a reflection of the wisdom of totality, a transformation of absolute wisdom.

This is what we practice, what we try to experience.

When you do experience this—the blissful rainbow body that is a transformation of the totality of absolute wisdom—when you have contemplated this enough, you see the sense world as illusory, in the way that a magician’s illusions do not exist as they appear to ordinary perception. When you have developed this understanding, even during session breaks, instead of appearing concrete, the outer, sense world appears as an illusion.

Of course, an illusion is also a type of manifestation; illusions exist. You can’t look at an illusion of a monkey conjured up by a magician and say that it doesn’t exist, that it’s not a phenomenon. It is a phenomenon; it’s just not a real, relative monkey.

It’s still energy; it’s still some kind of phenomenon; it’s still reality.

Why do we say that the phenomena of the sense world appear to us as illusory?

An illusion is something that does not exist in the way it appears; it’s not real. It’s a false vision; it gives us a false impression. It is misleading to believe in and follow it. Similarly, if we don’t see the objects of the sense world as illusions, in fact, if we believe the opposite, that these phenomena are real, dualistic, concrete entities, we are misled.

Why are all these relative conceptions, movements and energies illusory?

Because in appearance they seem to be real, whereas in reality, they are something else. The universal reality of all relative existence is something else; therefore, it is like an illusion.

Saying that relative existence is like an illusion is not just some philosophical fabrication. Nor does it mean that you lose your sense of proportion or your ability to discriminate and that everything gets all mixed up, like soup. It means that you see the phenomena of the sense world as an illusory bubble, simultaneously recognizing that these dualistic manifestations are actually non-dual in nature; they are born from the space of insubstantial non-self-existence and disappear back into it.

What is the psychological effect of seeing all this as an illusion?

This wisdom is the antidote, or the solution, to the extreme mind. For example, in the morning, for some reason, you might be extremely happy. Some bubble of excitement appears, you perceive and believe it and think, “Oh, fantastic! I’m happy.” You feel incredibly overestimated happiness. By receiving the relative bubble hallucinated vision of perhaps one chocolate from some bubble man or woman, you feel an incredible, extreme explosion of happiness.

In the terminology of Buddhism, such extreme happiness is negative. It’s too uncontrolled. Its nature, its function, its effect is to bring you down. So, in the morning, some bubble like that appears, and you’re interested. In the afternoon, nothing happens, so you’re bored. Your mind comes down; further and further down.

All our dealings with the relative world, all our up and down, being happy, unhappy, happy, unhappy, happy, unhappy, all these extreme feelings come from mistaken, dualistic perception, from holding ecstatic, happy objects and miserable, unhappy objects as concrete, self-existent, dualistic self-entities.

Beauty exists. I’m not saying that we have to reject beauty. What should concern us, however, is the way our projection of concreteness, independence and self-existence onto the relative bubble of transience, dependence and non-self-existent overpowers, overwhelms and dominates our entire reality.

How do you perceive that object of happiness or that object of misery?

How do you perceive that object of happiness or that object of misery?

If you see it as illusory and non-dual, extreme feelings that pump you up so that there’s no space for other feelings cannot function.

You have no unequal, unbalanced energy.

If we can recognize the unity of the absolute reality of these two extreme objects, if we can see how these objects are in reality equal in nature—and also in nature with ourselves, the subject—our lives will be balanced.

For example, in the morning you give your friend a chocolate: “Thank you so much; I’m so happy!” She’s extremely up. In the afternoon you’re busy doing something else and don’t have time to give her a chocolate; she’s completely down.

How can you handle that type of relationship? How can you keep it going? It’s impossible, isn’t it? You want to have a good relationship with that person but her psychologically extreme qualities make it impossible for you to maintain balance.

Of course, it’s difficult for her, too.

This is common. We’ve all had such experiences. In life, we get involved with different people. With some of them it’s impossible to communicate well and maintain good relationships because they’re so up and down.

Therefore, we need to keep repeating Lord Buddha’s mantra, TADYA THA OM MUNÉ MUNÉ MAHAMUNA-YE SVAHA. That’s why I always say TADYA THA OM MUNÉ MUNÉ MAHAMUNA-YE SVAHA. That’s why at the beginning of each teaching I like to chant TADYA THA OM MUNÉ MUNÉ MAHAMUNA-YE SVAHA.

That’s the answer.

You must relate your understanding of Dharma to your everyday life. For example, you always hear about the eight worldly dharmas. These eight extremes arise from the unbalanced, dualistic mind, the belief in concrete self-existence within the sense world.

Such belief only makes the eight worldly dharmas stronger.

If you have realized the reality of non-self-existence, if somebody praises you, prostrates to you or anoints you with perfume while another criticizes you, complains about you or even beats you, you have the space to maintain balance.

Why is there space? Have you no mind? Are you out of your mind? Have you lost all feeling? Are you no longer human?

Western intellectuals might question me like this.

No—you have universal consciousness.

What you have lost is the attitude of fanatical, extreme, dualistic grasping. That mind has disappeared.

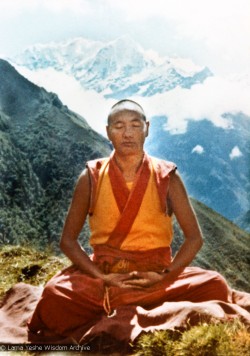

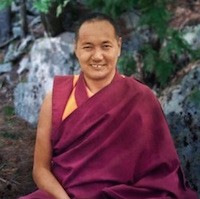

This teaching is an excerpt from a Commentary on the Yoga Method of Divine Wisdom Manjushri, given at Manjushri Institute, Cumbria, England, in August, 1977. Edited by Nicholas Ribush. Read more of Lama Yeshe’s teachings at Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

Relephant:

Let Go or Be Dragged.

Attitude is More Important than Action.

Author: Lama Yeshe

Editor: Renée Picard

Images: via the author

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 1 comment and reply