When a public person comes out as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, I notice.

Always—every time.

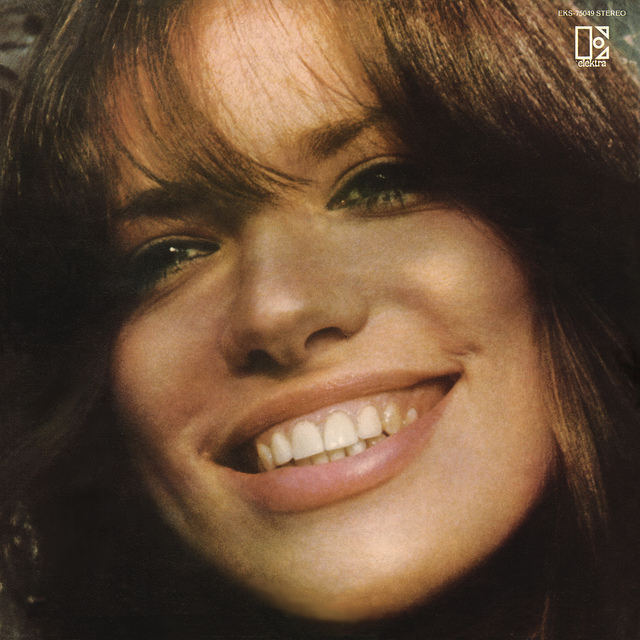

Carly SImon is 70 years old and is speaking about being molested when she was seven, which she has reportedly written about in her forthcoming memoir Boys in the Trees.

It’s still rare to hear survivor stories—they aren’t told often enough.

We are a culture that remains too silent about childhood sexual abuse.

We are a culture that is uncomfortable when people speak up about having been sexually abused.

We are a culture that has difficulty facing the fact that most childhood sexual abusers are known by those they abuse. Trusted—even loved. Family members. Coaches. Neighbors. Teachers. Religious leaders.

So when I saw the headline saying Carly Simon was sexually abused as a child, and she is speaking about it now, I read about it right away. I put my hand to my heart—I wanted to hear what she had to say.

Whenever a survivor speaks, it’s a spark that creates a light, which can bring change.

When a survivor speaks up, it is a knowing nod to other survivors who are still silent—those who may be afraid or ashamed.

It is a way of saying, “You are not alone, and the words may still have yet to form—be said and spoken. And there’s time.”

It is a way of saying, “This has happened. This happens now. We must protect our children.”

Children are most often abused by people they know—even Carly Simon. She was abused by a teenage boy who was a friend of the family.

Children are often not believed when they do speak up as children.

Even Carly Simon—her sisters didn’t believe her when she told them what had happened.

Children—even loved children—are not always protected, even in what should be the safest of places. Their own homes.

It’s a problem that is enormous and not uncommon, even now.

Part of the problem is that so many of us have so much trouble believing that people we know are capable of violence—so we just don’t believe it.

Even when it’s true.

In many ways, it’s easier for people to not believe abuse happens, than to deal with the reality that it does.

So we don’t.

Survivors know—people don’t want to hear it, see it, deal with it or respond. We know.

We know by how we’ve been treated—and what’s been said to us—when we told, tried to tell or suffered in silence.

What and who are we protecting with silence? Who and what does it protect?

Not children. Not the adults we become. Not even the perpetrators who don’t get treatment or punishment and aren’t held accountable.

But silence is understandable.

Survivors, violated and betrayed to begin with, are often further injured when they come forward. When we come forward.

Instead of being asked, “Are you okay?” We are often asked, “Are you sure it was abuse? Are you sure it was that bad? Are you sure you want to make a big deal out of it?”

As though it’s not violence—not a crime that has happened.

Imagine if someone reporting a home invasion was asked, “Are you sure you didn’t just lose your sh*t? Can you just let it go to make for easier holidays for the rest of us? How valuable was the jewelry anyway? Maybe you just want to keep this to yourself and not tell anyone?”

That is how survivors are often treated.

That—or worse.

Some are accused of lying, or making stuff up, to be hurtful or selfish or cruel. Some are shamed, shunned and cut out of the family.

Why?

This keeps us all from dealing with the reality of childhood sexual abuse openly and effectively. It prevents us from healing, recovering well, re-establishing trust and protecting others.

Silence is easier. Silence seems easier. Silence is expected.

Survivors are encouraged to keep silent—by abusers who often threaten or manipulate, by family members who “can’t believe it” or who are made uncomfortable and by a society that suggests these are issues that should be worked out in a home.

Who and what are we protecting when we insist on silence?

We need to get more clear, open and vocal on the topic of childhood sexual abuse, because it makes people uncomfortable.

We need to talk more about safety, bodily integrity, boundaries and respect for children’s bodies. We can’t work on prevention if we don’t acknowledge this is a serious and frequent problem that faces by 25 to 33 percent of all children.

We can’t share tips on recovery and healing, if we can’t say what we are struggling with and healing from.

But ending the silence requires more than words.

It requires listening.

We need to listen.

When children speak in symptoms (bed wetting, food problems, behavior issues.)

Or when children (or adults) find the words.

We need to respond when people share—like Carly Simon is doing.

We need to say, “Thank you for telling the truth.”

We need to say, “I’m sorry that happened to you.”

How can I help? What can be done now?

We need to learn.

Carly Simon’s abuse started when she was seven years old—she is talking about it at age 70.

All the way driving home, I kept thinking, “Carly Simon is a survivor.”

I felt compassion for that pained girl and woman too. I felt admiration for the strong woman and the scrappy kid who survived.

Just seeing her face, after reading her words, I could see that telling her truth is powerful.

This celebrity, who has graced us with the power of her words in song for years and years—this gifted and talented musician and lyricist—she is also a survivor.

Her admissions reach my core as much as her music does—they are folk wisdom wise and tender, they are a rocking anthem of rebellion, they are lullaby truth, chant and mantra.

She is not alone.

I am not alone.

We are not alone.

.

Relephant:

How to Tell your Lover you Survived Childhood Sexual Abuse.

Author: Christine “Cissy” White

Editor: Yoli Ramazzina

Photo: Flickr/Lawren

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply