In the early years of my marriage, living in a tiny walk-up apartment in Brooklyn, my husband and I kept a gratitude basket—a small basket with scraps of paper and a pen, where we could write down the simple things we were thankful for throughout a given year.

We’d open up the little folded-over pieces of paper, and read the notes together on the first day of each new year.

My husband died tragically—just six years into our marriage, at the age of 33. Even though it was only July—and even though I had a funeral to plan and a 21-month-old baby to tend to—I took that basket to my bedroom to unfold the notes, to read what he had written. I knew it was important, but I’ve only just recently understood why, as I’ve been pondering modern displays of gratitude in this month of Thanksgiving.

It’s trendy to be grateful these days, and moreover, to do so publicly. It’s another way of being mindful—which is also, of course, quite trendy.

Public nominations for sharing “gratitude lists” with a network of friends on Facebook are tossed about nonchalantly. There are pictures posted—an aerial view of a mug of espresso and steamed milk with a leaf design in it, a selfie with sunglasses from the front seat of a car, ugly feet (I’m sorry) on hammocks—all with words like, “Warm coffee on a rainy day- perfect,” or “On the beach, new novel in hand, and kids playing nearby. Life is good.” It sounds as though we’ve all gotten our writing voice from those Citibank commercials, in which a listing of three items is followed by one word of summation.

Having had a tradition of gratitude in my own home, I couldn’t quite figure out why certain snapshots of gratitude I saw online didn’t sit well with me. I wondered if it was the inherent staging aspect of these public displays that bothered me. I’m appreciative of the cup of English tea, and I often make before sitting down to do my morning writing. Having fresh flowers on my dining table always makes me happier. I could take photos of these right now and post them up for the public eye—“English tea, flowers on a November day. Grateful.” But if I do, would I feel it necessary—before I snap my shot—to move the clutter on my table out of the way?

Staged homes remove the uniqueness of the family that lives there—they take away personalities and quirks and interests and life. It is a still life—and life is not still. In a society of Instagramers and Pinteresters, the temptation to stage our lives might be taking away the setting—the space and contrast where beauty is most striking and gratitude most necessary for survival.

The context and background, out of which gratitude arises, is personal and difficult to capture in a public online snapshot. I suppose it’s still gratitude to be thankful for something that’s already beautiful or innately good—but I admit, I miss the grit. When the gratitude is publicly displayed—minus the context of the grit of life—this can actually lead to isolation, rather than a drawing together of our common bonds as human beings. A bond that we feel most acutely, not in abundance, but in dearth—like the bond between two young widows who’ve shared stories online, or the closeness between AA members who’ve answered late night phone calls to stay sober, or the bond felt between all New Yorkers who’ve found paperwork from skyscrapers and ash strewn in their yards on a September day 14 years ago.

Gratitude finds meaning and hope in the context of life in all its fullness—in both the glorious and horrifying. Corrie ten Boom—a Dutch survivor of the Nazi concentration camps—shares in her book, The Hiding Place, how her sister Betsy found things to thank God for, even in the camp. She thanked him for the fleas infesting their tent, something that confounded Corrie, but later proved useful when the guards avoided their barracks, because of those fleas, resulting in the women getting more freedom.

Minus the grit, some of this thankfulness almost reads as entitlement. Photos of lattes and beaches of white sand speak more of accomplishment and self-sufficiency, than the surprise of finding a gift you didn’t earn. Brother David Steindl-Rast, a Benedictine monk, says that “gratefulness is the inner gesture of giving meaning to our life by receiving life as gift.”

In fact, gratitude and grace come from the same root word. In Latin, gratia means “a given gift.” In a world where we are always trying to keep things even, and pay people back, it’s humbling to receive something we haven’t earned. Even though life is hard, and we’re not perfect, there is this redemptive thread of goodness we find running through it that surprises us. It is often dark and infested, but still—the gift. This kind of gratitude feeds hope, not our ego.

When I think of grit and grace, I inevitably think of Flannery O’ Connor. The shock and violence of her short stories was intended to wake the readers up to their need for redemption and grace. “Our age not only does not have a very sharp eye for the almost imperceptible intrusions of grace, it no longer has much feeling for the nature of the violences which precede and follow them,” she wrote.

Gratitude does not arrive in a vacuum. We are in a life of shadows that only lose their power when they’re brought into our consciousness—that only lead to redemption and transformation when they’re acknowledged—sometimes painfully. To edit out the grit or darkness in our lives might edit out what O’Connor would call—the moment for grace to enter.

Opening up my husband’s notes of thankfulness, just days after he had died, I was searching for more than one thing. I was searching for clues—trying to make sense of something so illogical. I was searching for anything new of my husband, as people often do when someone dies. But also, there had been that violence that O’Connor speaks of— that shock—and I’m pretty sure, in those small creased pieces of paper, I was looking for any crumb of the redemptive that might follow.

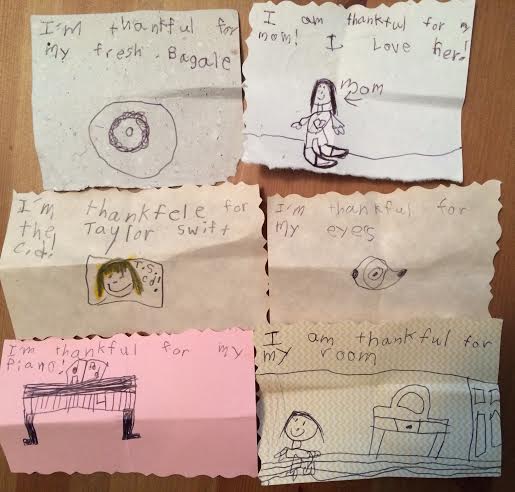

It took me a few years to do it, but my daughter and I continued the tradition once she could write, at age five. We take out our gratitude basket on November first, and read the notes on Thanksgiving, because I didn’t think I could ask a five-year-old to delay her gratification for an entire year. She also draws pictures with her words. Reading the things she’s thankful for, in her child’s handwriting, is powerful to me—but more so because of the context of our life.

My own notes affect me in a similar way. In the face of loss, we have found there is still so much to be grateful for. We have fed hope. In those little folded up notes is a secret—a treasure, that despite the grit, in the face of it, life is still a gift. What I treasure about our basket is the secrecy—the folding up of tiny notes of thankfulness—the waiting, the fullness of gratitude over the course of time. In it, there is both shadow and light—there is patience and there is grace.

It turns out, being grateful is a rather wild, undomesticated thing—not just lattes and sunsets and rainbows. It might be Corrie ten Boom’s sister Betsy notoriously giving thanks for the fleas, in the bunk of her Nazi concentration camp. We discover hope, redemption and yes, grace—when we don’t disenfranchise the darkness.

This is gratitude—unedited, unfettered and shockingly lovely.

.

Relephant:

The Gratitude Agenda. {Plus 5 Great Quotes on Thankfulness}

Author: Julia Cho

Editor: Yoli Ramazzina

Photos: Flickr/Wicker Paradise; author’s own.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 2 comments and reply