The whole question is, What makes us happy? What kind of action does not bring an undesirable result? What do we have to do to be happy? That’s what we have to investigate clean clear.

Our usual situation is that we’re either kind of happy, somewhat unhappy or in between. None of these three states is any good. Emotional happiness, the sort we experience when we go out night clubbing or something, the sort that normally makes us say, “Now I’m happy,” is not happiness. It’s what we might feel when we act out of grasping attachment and it causes us to generate more grasping: “I want more, I want more.” Each time we experience this kind of happiness and cling to it we’re laying down more and more thick imprints on our mind, imprints that will cause us to keep on grasping at unreal happiness without end.

For example, many of you left a comfortable life to come to this course, where the conditions are relatively unpleasant. You’re unhappy with the austere situation here because you’ve brought with you an idea of how things should be: the rooms should be very clean; the bathrooms at least should be up to a certain standard. You have a fixed idea of what constitutes pleasure based on your life in the West: “Things should be like this; my life should go this way.” But you can never make predictions about life; it is constantly changing and you’re always having to experience different states.

Anyway, the reason you’re uncomfortable or even miserable here in Nepal is because of the reactions of your grasping mind. The Nepalis don’t mind. They’re happy. They’re also human beings. Their bathrooms are worse than ours. But our dualistic mind, the mind that’s always making comparisons, “I’m this, so I can’t deal with that,” creates all this conflict. So of course we’re not happy.

The thing is, therefore, that whatever we think is happiness is actually the cause of misery. It might be difficult to accept that fact but it’s a profound truth. If you check deeply you will see that this is correct. And in many cases what drives this is ambition, the emotional ambition that is so prevalent in Western culture. For some reason, your society, culture, life, background, whatever it is, makes everybody incredibly tense. It’s emotional ambition. It makes you unstable. This ambitious mind is psychologically sick.

How sick? It makes you very self-sensitive. Insignificant things make you happy. Somebody gives you one small chocolate and you feel, “Oh, I’m so happy with this chocolate.” Then when that person doesn’t give you a chocolate you get miserable and unhappy. It’s not the chocolate or absence of chocolate doing this, it’s your mind.

Therefore you need meditation to understand the tricks your mind plays on you. It is your mind, not your body. Whenever you experience samsaric pleasure, not knowing its reality, you have the expectation that it will last, that it will continue, that you’ll have more pleasure. Which is not possible. It’s not made that way. It’s not in its nature to last. But you can see how this attitude produces more attachment. And you can see how it makes you unhappy: you want it to last but it finishes. That’s obvious; I don’t need to explain that.

Whenever you’re unhappy, anger and hatred tend to arise. You can see this with people who contract some kind of physical illness. They become very sensitive and are easily prone to anger. Before they got sick they were okay, but when they’re ill you can’t even say anything to them. They’re so tense and easily upset. It’s the underlying unhappiness that causes this. There’s an expectation of feeling good all the time, so when they get sick, people get unhappy and their dislike is converted to hatred. “I dislike my disease; I dislike what’s happening to me.” This dislike generates hatred. So when even family and dear friends approach, that dislike or hatred is projected onto them. It’s incredible, the trips the mind takes.

Once when I was in the refugee camp I had a stomach ache and the idea came into my head that I needed some thugpa [Tibetan noodle soup]. So I told my brother to bring me some thugpa but he brought something else. I had this incredibly fixed idea, this grasping mind, that I had to have thugpa, so when he came back without it I was really unhappy. It was unbelievable—I couldn’t believe myself! I was so ridiculous. This is what sickness can do to you. You become hypersensitive and ready to dislike anything, so even a small thing can make you completely freak out.

Once when I was in the refugee camp I had a stomach ache and the idea came into my head that I needed some thugpa [Tibetan noodle soup]. So I told my brother to bring me some thugpa but he brought something else. I had this incredibly fixed idea, this grasping mind, that I had to have thugpa, so when he came back without it I was really unhappy. It was unbelievable—I couldn’t believe myself! I was so ridiculous. This is what sickness can do to you. You become hypersensitive and ready to dislike anything, so even a small thing can make you completely freak out.

The point is, the nature of dissatisfaction is hatred.

You can see the same thing in interpersonal relationships. When you don’t get satisfaction from somebody you can easily dislike or even hate that person.

So I mentioned before our three usual states of being. When we’re in between—neither happy nor miserable—that’s not good either, because even though we might not be either grasping at happiness with attachment or generating hatred toward someone or something, we’ll still be unaware of reality; we’ll just be in a state of dull ignorance.

Check up your own life. When you’re experiencing some kind of temporal happiness or sentimental pleasure, what does your mind want? Your mind wants it to last, to go on and on, to get even better, to increase. Of course, it’s not in the nature of temporal pleasure to last forever or even a long time, but if you have the concrete expectation that it will do so you will end up feeling hopeless and frustrated.

If you understand such life situations, the interactions between mind and life, you can easily see how life itself is, in general, uncomfortable and agitated. It’s not because of your body, it’s because of your uncontrolled, dissatisfied mind. That’s what makes you miserable. So, this is how life goes—round and round, in a kind of circle. Life itself is cyclic existence, samsara.

~

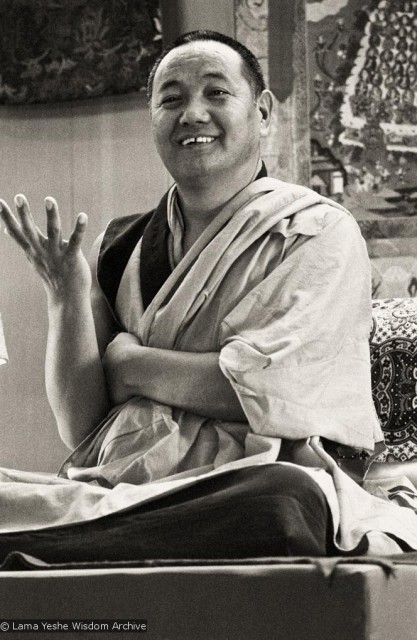

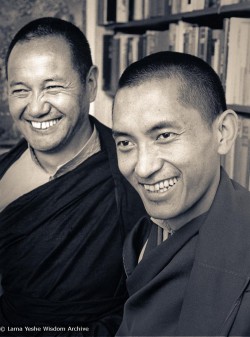

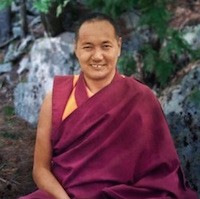

Lama Yeshe discusses what makes us happy, at the tenth Kopan meditation course, November 1977. Edited by Nicholas Ribush.

See also the second part of this talk, That’s the Lam-rim!

Read more of Lama Yeshe’s teachings at Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

~

Editor: Toby Israel

Images: (1) Carol Royce-Wilder, (2) Carol Royce-Wilder, (3) Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive

~

Read 1 comment and reply