We came here to Palestine to stand in love and revolutionary struggle with our brothers and sisters

We come to a land that has been stolen by greed and destroyed by hate

We come here and we learn laws that have been co-signed in ink but written in the blood of the innocent and we stand next to people who continue to courageously struggle and resist the occupation

People continue to dream and fight for freedom

From Ferguson to Palestine the struggle for freedom continues

This is Black History Month, a time dedicated to reflection on the terrible legacy of the African Holocaust, slavery, segregation, and the ongoing struggle against American racism. Next month will see Israeli Apartheid week and the “Support Palestine Protest AIPAC” events in Washington, DC, to protest the 68-year ethnic cleansing, genocide and racist oppression of the Palestinian people by the Israeli state.

Both of the African-American rights and Palestinian Liberation movements have grown and evolved significantly in the past few years, and largely for the same reasons: (1) the rise of a new generation that has little tolerance for structural racism; (2) the replacement of mainstream media by alternative media as the primary sources of information about the world with social media as a platform for political networking and action; and (3) horrific events on the ground, in both the U.S. and Palestine that have raised both public awareness and the sense of urgency to act. The two struggles are furthermore linked, both historically via their common roots in a millennial history of European expansion and the ideologies to justify it and structurally, via a host of similarities in form and practice. The strategic alliance of these movements is also part of a broader emerging approach in social justice activism known as “intersectionality.”

The Atlantic Slave Trade was made possible by the dehumanization of a people. Earlier systems of slavery in the medieval Mediterranean were not race-specific, but near-simultaneously the opening of the Americas and the sub-Saharan African coast to European exploitation in the 15th Century, combined with the spread of sugar production (ironically originating from the Arab World) and the relative disease-resistance of Africans compared to indigenous Americans, made the enslavement of Africans economically attractive. Slavery soon became equated with Africans, and the foundations of modern racism were laid. In spite of centuries of struggle, the legacy of this history remains with us to this day in our social inequalities, our cultural representations, and our manifestly discriminatory law enforcement and justice systems.

The State of Israel is the last major European Colonial project, based on a strain of European nationalism developed at the height of the Colonial Age. Like other nationalisms that were emerging at the time, it mobilized ethnic, religious, cultural and other markers as the basis for the construction of a political ideology based on an ethno-specific nation-state. Although Jews had been living peacefully in Palestine for centuries alongside Christians, Muslims and Druze, the European settlers who began to migrate there as part of this movement in the late 19th Century did not seek coexistence or integration into the existing local society, but the creation of a new and specifically “Jewish” state in an already inhabited multi-religious land. The ensuing invasion, expansion, violence and aggression against the indigenous Palestinians that ultimately dispossessed them of virtually all of their land was always presented as self-defense, much as the ethnic cleansing and genocide of the American Indians had been decades earlier.

Both expansions were animated by ideologies of “Manifest Destiny” and ethnic supremacy. Both justified ethno-religious segregation, exclusion and dispossession through the criminalization, demonization and dehumanization of those it sought to exclude or exploit. Both sought the concentration of unwanted populations into ever-shrinking reservations, Bantustans or territories. From the inner cities and reservations of the U.S. to the cités of France, the favelas of Brazil, and the townships of South Africa, marginalized populations are ever met with shrinking opportunity and escalating violence. A similar process can be seen at work in Palestine, especially in Gaza. Israel’s involvement in the militarization of policing in the U.S., Brazil and elsewhere, and in the construction of the Mexican Border Wall, also demonstrate that these systems are directly linked today, just as Israel was linked with apartheid South Africa.

But overt forms of oppression, such as expulsion, occupation, slavery, segregation and legal and structural inequality are only part of the story; oppression is further justified and struggles against it weakened by an array of strategies. One of the most typical of these is a pervasive maligning of the victims as dangerous, criminal or even less than human, thereby adding insult to injury. Another is their separation from their sister struggles, which shrinks their base of support and obscures the deep similarities among them. The occupation of Palestine is justified through a particularist discourse, focused on “Jews vs. Arabs” or “Jews vs. Muslims.” Oppression gains strength in the division of the oppressed. When the struggle is framed in terms of universals, however, such as rights, equality and justice, larger truths emerge from the morass of particularities. This is how Gandhi, King and Mandela were able to humanize and universalize their struggles.

Linking the African-American and Palestinian struggles is not new. Malcolm X noted the similarities between them as early as 1964, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) declared solidarity with Palestine during the 1967 War, Huey P. Newton discussed the issue in 1970 (“On the Middle East”) and a group of Black leaders called for “Afro-American solidarity with the Palestinian people’s struggle for national liberation and to regain all of their stolen land” in a letter to The New York Times that same year (“An appeal by Black Americans against United States support of the Zionist government of Israel”). Angela Davis, Cornell West, Toni Morrison, Cynthia McKinney and others have since spoken out for the Palestinian cause and Nobel Prize-winning African-American author Alice Walker sailed on the 2011 Freedom Flotilla to Gaza and called the Occupation “more brutal” than the Jim Crow South of her childhood in 2012.

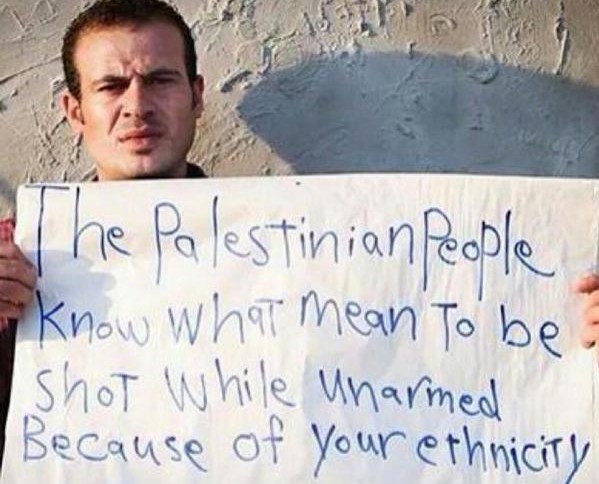

A watershed seems to have been reached, however, in August 2014, when Israel’s brutal Operation Protective Edge happened to coincide with the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Palestinian journalist-activist Hamdi Abu Rahma posted a photo on social media in solidarity with Ferguson and similar photos were soon being posted by protestors in Ferguson in support of their Palestinian brothers and sisters. In January 2015, a delegation of African-American activists from Los Angeles, Miami, Chicago, New York, Ferguson, and Atlanta visited Palestine and proclaimed their support of BDS (the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions campaign).

The February protest against the AIPAC annual meeting, #ShutDownAIPAC, featured an event entitled #OneStruggle, with speakers from Palestinian, African American and other oppressed groups. In August, more than 1,000 African American activists and intellectuals signed a letter affirming “solidarity with the Palestinian struggle and commitment to the liberation of Palestine’s land and people.” September alone saw numerous events around the U.S., including the panel discussions, “From Ferguson to Palestine: Connecting Struggles” at the University of Texas-Austin, “CUNY Stands for Justice: From Ferguson to Palestine,” at The City University of New York (CUNY), and “From Gaza to Ferguson,” at the UCLA Law School; protests and vigils, like a public reading of “the names of the lives lost, give speeches, and stand in solidarity from Ferguson to Palestine” by The College of Staten Island’s SJP chapter and a protest at ADL office in San Francisco by the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network (IJAN).

In October, more than 60 African-American and Palestinian artists and activists, including Lauryn Hill, Danny Glover, Cornel West, Angela Davis and Alice Walker, released a video entitled “When I See Them I see Us.” On February 9th, Angela Davis released a new book, entitled Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine and the Foundations of a Movement, which emphasizes the parallels and connections between the Black and Palestinian oppression and the liberation movements developed in the face of that oppression.

These developments have not been lost on Israeli and pro-Israeli forces. An opinion piece just last month in the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz warned that “the growing acceptance of intersectionality arguably poses the most significant community relations challenge of our time,” and concluded rather pessimistically: “We may not be able to discredit intersectionality with Israel across the board, but we can limit its reach.”

Both the Palestine Solidarity and Black Lives Matter movements have grown considerably in the last 2 ½ years, as have the efforts to link them. There are furthermore many other anti-Colonial Struggles that could be allied in this way—Native Americans, Black South Africans, Australian Aborigines, Afro-descendants and Indigenous peoples in many countries—and some efforts have already been made. A globalized struggle against the ongoing legacy of Colonial oppression has the potential not only to de-ghettoize particular struggles such as Palestinian Liberation by reframing them around issues of universal human rights (as opposed to a “conflict” between two peoples), but it can help us to better understand and overcome both the longer-term processes that unite these struggles historically and the strategies by which oppression is maintained.

In a world that is both the product of globalization and still in the process of globalizing today, globalized control and domination must be met with globalized resistance.

~

~

Author: Peter Cohen

Editor: Travis May

Image: Courtesy of Author–Used with Permission

Read 1 comment and reply