“Why” is a common and often useful word, but one which can also be misleading and unhelpful.

Last summer I taught in a personal growth training. A participant in the training—who was in the midst of a difficult divorce at the time—shared this example that illustrated how “why” can easily get us into trouble:

“My five-and-a-half year old daughter had been saying, I feel lonely and I don’t feel loved. At first I was saying, But why? Mommy loves you and Mommy does this and this …And then I saw that asking “why” wasn’t eliciting any response from her. Instead, it shut her down. And I was left wondering, what can I do? So I said okay, how can I help you feel better? My daughter said, I just want you to hold me, kiss me, and hug me. So I did just that.”

This is a lovely example that shows how simple some problems can be as long as we know the right questions to ask.

So what are the principles at play? Why is why an unhelpful question to ask in this context, and how is how a helpful one?

The question how? gathers specific information about the experience that underlies the daughter’s words. The question, “How can I help you feel more loved and not so alone?” invites the daughter to specify the vague process words loved and lonely. Mom then learns which specific actions equal love and non-loneliness to her daughter: holding, kissing, and hugging. Without this information, Mom could have attempted countless new things she thought would demonstrate more love to her daughter—quite possibly at great expense—and, her daughter may have continued to feel just as lonely and unloved.

In this case, the question how was all that was needed.

In contrast, why is a general question which invites the person to come up with reasons which can be difficult to answer.

Imagine you’re the daughter saying, “I don’t feel loved,” and your Mom responds by saying, “But why?” If I imagine myself as a five-and-a-half-year-old, I also shut down when confronted with this question. I don’t know why I don’t feel loved, I just know that I don’t feel it. Coming up with a why is much too open-ended and difficult to answer. But when my Mom asks me how she can help me feel loved, that is specific enough that ideas immediately spring to mind—hug me, kiss me, and hold me!

Even as an adult it can be challenging to answer the question why?. “I don’t know why I feel this way” or “I don’t know why I did that” are phrases I’ve often heard from friends and clients, and have certainly said myself. Philosophy and religion are devoted to answering various aspects of the question why and predictably the answers vary widely! Whether five years old or fifty years old, why is a tough question to answer, and most of the time we’re better off not trying.

Explaining why problems are the way they are is not only difficult and time-consuming, it also keeps us focused on the problem state. This can have the effect of solidifying our problems in place, not only because it keeps our attention on what’s wrong but also because now we have justifications and reasons for our problem’s existence. When Mom asked her daughter, “How can I help you feel more loved?” she did the opposite of this, elegantly guiding her daughter from the problem-state “I don’t feel loved” to a solution state in the future, “How can I help you feel better?”

In addition, why can imply blame even if that was never the speaker’s intention. Though Mom was simply trying to understand her daughter, Mom’s question “Why don’t you feel loved when Mommy does this and this…?” can feel like judgement or blame to the child, particularly if the mother’s voice tone is annoyed or exasperated. This can elicit guilt: “Gosh, why don’t I feel loved when she does all those things for me? Maybe there’s something wrong with me.” Or it might elicit defensiveness, “Why are you expecting me to feel loved when I don’t!”

Let’s look at this using another example. Imagine your partner or friend or co-worker accidentally starts a fire in the microwave again because they forgot to remove their metal spoon, and you say, “Why did you forget your spoon in the microwave again?” Now step into the shoes of the other person and imagine being confronted with this question. Even if asked in a neutral voice tone, I’m likely to either respond defensively “Nobody’s perfect!” , feel guilty “I’m sorry, I screwed up again,” or even worse, “I’m such a screw-up!” These kind of responses divert my attention away from possible solutions and into feelings of defensiveness or failure, which are neither fun nor useful for problem-solving

In summary;

- Why is vague.

- It focuses our attention on the problem.

- It tends to elicit answers that hold the problem in place.

- It can be taken as blame or judgement.

Finally, here’s one more way I’ve noticed why getting people into trouble. When we say, “Why did you do X?!” in an angry or frustrated tone of voice, we aren’t usually interested in the answer to that question and we don’t want to hear a bunch of justifications. Instead, there’s usually something we want to express.

If a spouse is angry or frustrated and says, “Why did you get home so late!” they may want to communicate something such as, “You came home a lot later than planned, and this made things really difficult for me. I was planning on you taking over with the kids so I could get ready for my evening meeting.” With the microwave example, asking, “Why did you forget your spoon in the microwave again?” could really be translated into something like, “I’m concerned about our safety and want to make sure no fires get started in the building.”

So when we find ourselves about to use why we may want to ask ourselves, ‘Is there something I want to say here? Am I expressing my needs and goals clearly?’

Learning how it happened that one’s spouse came home late, or one’s roommate left the spoon in the microwave, can be a useful part of the discussion. This is much more specific than asking why—and it works the best in the context of understanding each person’s wants and needs. With this information we can then move away from the problem and toward future planning and solutions. In the case of the Mom and daughter example above, it worked to move straight to future solutions with the question, “How can I help you feel more loved?”

Any time we find ourselves asking why in the context of an interpersonal problem or difficulty, we have an opportunity to change why to how and in doing so shift our focus from the problem to future solutions.

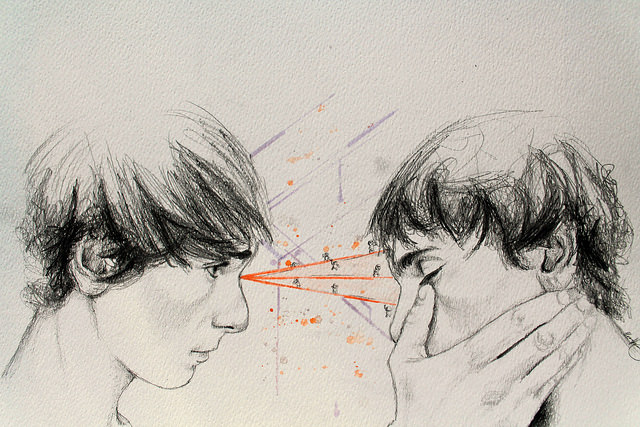

This simple Jedi mind trick can improve our relationships.

Relephant:

3 Ways to Resolve Conflict in Relationships.

Author: Mark Andreas

Editor: Renée Picard

Photo: lucahennig/flickr

Bonus:

Read 7 comments and reply