I’m fully prepared to make some yogis angry by writing this.

Ashtanga Yoga is revered in the West, and with good reason. It was one of the first styles of yoga brought to North America and gained a huge following in the middle-to-late part of the 20th century. It birthed many of the styles of Vinyasa Yoga practiced today. Pattabhi Jois, the father of Ashtanga yoga, is one of the most influential yoga teachers in modern memory.

I, too, respect the Ashtanga tradition. I get why people love it for its structure and discipline. I understand how and why it changes people’s lives. I’ve sweated my way through led Primary Series classes and shown up for early morning Mysore practices. To use a tired cliché, some of my best friends are Ashtangis.

And yet, the longer I practice and teach, and the more I learn about the science of anatomy, the more I think Ashtanga gets it wrong and, in some cases, may be doing more harm than good. Here’s why:

Those great teachers weren’t anatomists. The Ashtanga lineage traces its roots back through Sri K. Pattabhi Jois to Sri T. Krishnamacharya. It’s impossible to overstate the influence these men had on the practice of yoga in the 20th century. Both together and separately, they developed and codified a system of yoga that has been delivered to millions of people. But these men were not anatomy experts. While they were both learned men, neither had any formal education on the physical workings of the body. Because of this, their systems of yoga have some anatomical blind spots.

We know better now. In the last 30 years, scientific knowledge about the body has grown exponentially. We have new tools and techniques to help the body develop strength, flexibility, and overall health. Many styles of yoga have integrated this new information and evolved the practice in exciting and beneficial ways. I believe the role of yoga teachers is to grow the practice as new information becomes available, throwing out old and ineffective ways of moving in favor of new movement paradigms.

It’s stuck in the past. Ashtanga yoga is taught very much the same way it was 50 years ago. No other movement discipline can say the same. Every type of movement—from running to dance to martial arts to elite-level sports—trains its practitioners very differently than it did half a century ago. This is precisely because of the gains in anatomical knowledge made in recent decades. Ashtanga yoga practitioners have steadfastly ignored anatomy research in favor of adherence to “tradition,” leaving practitioners set up for injury and ineffective movement techniques.

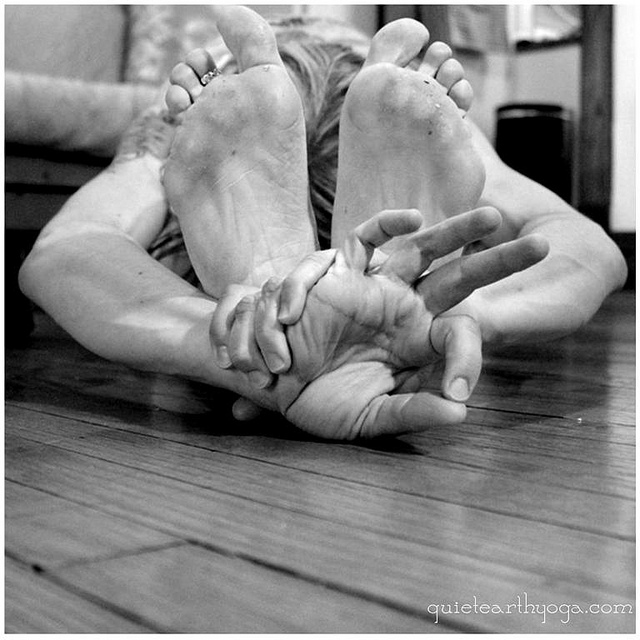

Joints are treated badly. One of the most important outcomes of anatomy research in recent decades is a new understanding of what constitutes healthy movement. Simply put, healthy movement can be defined as “a little bit of movement from a lot of places.” In other words, many joints and muscles must help make an action happen. The traditional cues of Ashtanga Yoga ask practitioners to do the opposite and force a lot of movement into a small number of places. For example, in any forward fold, Ashtangis are cued to “keep the spine straight and hinge at the hips.” In other words, a lot of movement from a few places. This can put a great deal of compression on the hips and strain the lumbar vertebrae. Cues like this encourage unhealthy and injurious joint movement.

Muscles are treated badly. Muscles are designed to do certain jobs. It is possible, however, to train muscles to not do their job, which sets the body up for injury. For example, Ashtangis are taught to “relax the glutes” in backbends, with the erroneous assumption that doing so will allow for a deeper backbend. One of the functions of the glute muscles is to stabilize the sacrum and lumbar spine. When those muscles are trained to relax over time, the curvature of the backbend is shoved into the SI joints and lumbar vertebrae, creating an uneven and dangerous distribution of force in the joints.

Moreover, as glutes and their surrounding muscles are trained to go slack when they should be working, the attachments of those muscles start to weaken. A common injury amongst advanced Ashtanga practitioners is a tearing of deep hip and gluteal joints away from the bones. (Yoga teacher Diane Bruni has written and spoken widely about her experience with this type of injury after many years of advanced Ashtanga practice. Her story is worth Googling.) This type of injury is intensely painful, takes a very long time to heal, and can be traced directly back to common cues of the Ashtanga practice.

Repetitive stress is real. I can’t say this one enough: Repetitive stress is real. Doing the exact same motion over and over can and will injure your body. Ashtangis often practice the same series six days a week for years at a time. There are 60 Chaturangas in the Ashtanga Primary Series. Multiply that by six, and you have 360 Chaturangas a week. That’s over 1,400 Chaturangas a month. There’s nothing inherently wrong with Chaturanga when performed with proper alignment, but that many per month for months or years at a time puts enormous strain on the shoulder girdle, rotator cuffs, wrists, elbows, and shoulder joints. Joints need a variety of movement over time to maintain health. Doing the same thing over and over puts unnecessary strain on joints and creates the potential for injury.

Deep adjustments are invasive and injurious…and they don’t do what you think. A hallmark of the Ashtanga practice is deep adjustments applied by the teacher to get the student into the preferred alignment of the pose. Some Ashtanga teachers are sensitive enough to ask before touching a student, but many are not. It’s impossible to know whether a student has experienced trauma or has some other reason to not wish to be touched. To lay hands on a student and manipulate them into poses their bodies might not be ready for could leave them feeling violated with no outlet to express that to the teacher. In addition, this type of manual manipulation puts the focus on what the teacher can do for the student, rather than what the student can do, thus disempowering the student and creating dependence on the teacher. And of course, manipulating someone’s body into a space it’s not ready to go on its own creates the potential for teacher-caused injury.

Bodies are more diverse than that. Human bodies come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and configurations. Some bodies have more adipose tissue to work with. Others have more longer bony protrusions in the skeleton, which means they hit bony compression in the joints sooner than others, limiting range of motion. Others have proportions that don’t allow them to create certain shapes. Some bodies need to work on building flexibility; others need to develop strength. Ashtanga Yoga takes a one-size-fits-all approach to the human body that is simply unrealistic given the diversity of bodies that show up to the mat.

There is no perfect alignment. One of my teachers, Yoga Anatomy expert Leslie Kaminoff, says “Poses don’t have alignment; people do.” Ashtanga Yoga assumes that every body is capable of achieving every pose. Moreover, the system assumes that, if the practitioner cannot achieve a certain pose, it is the fault of the practitioner, not the pose. The traditional Ashtanga Yoga system ignores the inherent biodiversity of the human body in favor of false ideas about “perfect” alignment. In traditional Ashtanga Mysore rooms, a practitioner is often “tapped out” by the teacher if they can’t achieve a pose, meaning they have to stop their practice at that point in the series, do the finishing series, and leave the room. This continues until the yogi achieves the pose, when they are granted permission by the teacher to move forward. This approach disempowers the student, shifting the focus from an intuitive relationship with the body to the teacher’s assessment of a student’s progress.

I want my practice to support my life. The more I study anatomy and student-teacher dynamics, the more I think Ashtanga often gets it wrong on an empirical level. But ultimately, practice is a subjective personal choice, and Ashtanga Yoga doesn’t support the kind of life I want to live. I want a practice that builds self-compassion, not one that pushes me to “achieve” a pose. I want a practice that leaves me feeling empowered and intuitive, not one that forces me to depend on a teacher. And I want a practice that meets my needs in the moment, not a prescriptive series that doesn’t take my unique needs into account.

Do I think people should stop practicing Ashtanga Yoga? Of course not. But I think it’s important for yogis to question techniques that haven’t evolved in decades. We can and must evolve our practices based on new anatomy research, and perhaps make the practices we love even better.

~

Author: Melissa Scott

Photo: Amy/Flickr

Editor: Travis May

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 1 comment and reply