A friend has completed yoga teacher trainings in four or five different styles.

She has also completed specialized workshops with numerous practitioners from different schools of thought.

She’s young and well aware that she’s still learning, still in training, still open and receptive. She tells me of a man she knows who has been studying under one teacher for more than 15 years. He criticizes her approach, comparing it to digging for water, but only digging down one or two feet before giving up and trying again elsewhere. Then giving up again and moving elsewhere. Again and again. Continually digging new holes, and never getting anywhere.

Or, at least, never finding water.

This is an interesting metaphor, echoing the ancient gurus’ critique of young wandering yogis who refused to commit to a single teacher. The ancients called students who shop around, or pick-and-choose, “crows gathered at a sacred site,” which I’ve discussed previously. I’ve recently had the opportunity to think more deeply about this idea—not to revise my position, but to deepen my understanding of the reasons why I favour the pick-and-choose method.

There is, of course, merit to this critique. There are sound reasons to be concerned about people who pick-and-choose without developing an understanding deep enough to make informed choices. It is obviously possible to keep flittering from one teacher to the next without ever knuckling down to the hard work of pushing through the challenges, of facing one’s own insecurities, obstacles and blockages.

It’s not only possible, but all too common in our culture of commodified feel-good consumerism.

When I wrote about this before, I was discussing the difference between self-exploration and compliance with an authority. One of the reasons I object to submitting to authority on these matters is that those who proclaim to be authorities are (not always, but) too often charlatans. This is inferred in the famous line “If you see Buddha on the road, kill him.” Anyone who claims to be the Buddha (the Christ, the Truth, the Authority) is not.

Of course, the literature is full of stories of sages who insist that they know nothing, who tell their followers to f*ck off and follow someone else—someone who might have something to offer.

My inner cynic wonders if this is simply a brilliant strategy in reverse-psychology; my self-critic wonders how genuine I am when I tell students not to take my word for anything.

All of this came together for me during a recent week-long yoga retreat. The retreat was led by a dear friend who, like me, insists that his students should only consider his teaching as prompts for their own self-inquiry. Like me, he doesn’t want anyone to (mis)take him for a bearer of The Truth.

And, like me, he contradicts himself by becoming defensive when his version of the truth is challenged. I see this in him because I am often the one challenging his version of the truth in front of his students.

The point I’m trying to get to crystalized for me after he mistook something I said to mean that “yoga can be all things to all people” when he was presenting a rather narrow interpretation of the word yoga based in the etymology of the term (to yoke, or union), and grounded in the teachings of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. [Without getting defensive, what I was trying to say was much more along the lines of “yoga means different things to different people”—I was suggesting that we can find a lot of meaning along the yogic path without needing to “believe in” the final bliss state that Patanjali promises.]

It crystalized the day after this discussion, because I had chosen at the time to not argue the point (for a change) when he misrepresented my position, but was still stewing over it the next day (which we spent in silence). I was still stewing over his defence of a relatively narrow definition of yoga through our session in Qigong, and while he quoted Buddhist scriptures, invoked Zen koans, and cited contemporary physicists to move us further along the path of what he thinks is “really yoga.”

He and I have been having this discussion since he started on the yogic path some 16 years ago. We have been debating these and a myriad of other points for all of that time. During this particular encounter he shared with those who didn’t know our history an insight by a mutual friend, who had pointed out that we can argue ’til the cows come home, but are basically in agreement about most things.

As I was stewing over these things, I reflected on what I know about his journey on this path, training with various yogis as well as Zen masters, Buddhist teachers, and Ayurvedic healers. That’s when I started reflecting on the story with which I opened this piece. Some might be inclined to suggest that this diverse array of influences is: a) not “true yoga” and b) is akin to digging for water in a whole lot of places without ever going deep enough to find what you’re looking for.

While I was reflecting on this, I thought about trying to dig a hole in a place I know where you stick a shovel in the ground and hit a rock within two or three inches.

To dig any sort of a hole in this piece of ground you have to use a six-foot long steel bar. You lift the 20-lb bar straight up and thrust it into the ground again and again until you’ve loosened a bit of soil, then reach down with a spade, or your bare hands, and move the loose soil out of the way. Sometimes a mattock is helpful. Sometimes a sledge-hammer comes in handy. Then return to the rod.

Repeat until the hole is big enough.

It’s very hard work. It takes a long time to make any progress.

It’s all a lot like deconstructing your ego-self, cutting through the illusions of maya, trying to make sense of this fickle thing we call life. His wandering path through diverse teachings, different techniques, and varying perspectives has produced a diverse array of tools, helping to dig a much deeper hole in the quest for “water” than could ever have been achieved with only the garden spade he would have received from devoting himself to just one teacher.

Shopping around, picking-and-choosing, shifting and changing can be shallow and unproductive. It can be a way to avoid doing the hard work. But it can also be necessary to provide the range of tools required to break through the vast array of obstacles and distractions encountered on our path towards self-realization.

Author: Karl Smith

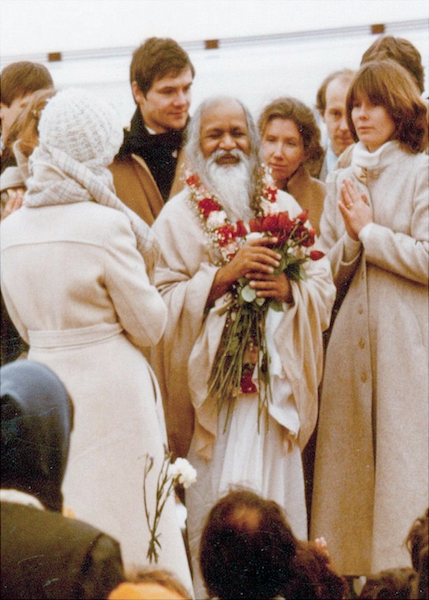

Image: Wiki Commons

Editor: Renée Picard

Read 0 comments and reply