Tigers are one of the most amazing animals on the planet.

Yet, according to 21st Century Tiger, one of the top financial contributors to tiger conservation projects around the world, a century ago there were nine subspecies roaming across parts of Asia and Europe, comprising approximately 100,000 individual animals.

Today the story is different.

With three subspecies being declared extinct in the last century, every single one remaining is in desperate trouble. The total number across all subspecies was estimated back in 2008 as between 3,500 and 5,180. The Asian tigers’ range has been reduced by 93 percent (no, that is not a typo) in the last century, and 40 percent of that loss has occurred in the last 10 years.

So, in spite of a dramatic and high profile, worldwide push to conserve these incredible creatures, it feels like the battle is being lost, and quickly.

So why is it so difficult to conserve a keystone species such as the tiger?

1. The good news is, its actually not that hard for tigers to make a comeback.

In recent comments over a highly publicized spat between prominent conservation bodies and scientists, tiger expert Eric Dinerstein points out that that “tigers are known for being able to rebound when given proper conditions, like when they have enough prey to eat.” Of course, having enough prey is heavily dependent on having enough habitat for that prey, and that is a problem, with industries such as forestry and palm oil production pushing ever further into the wild parts of the world.

2. That said, tigers are notoriously difficult subjects to study.

They are reclusive, nocturnal, and their numbers are small. Their preferred habitat is dense forest, which is not ideal for the best method of studying their habits and estimating their numbers—camera traps. This was, in fact, one of the reasons for the argument mentioned above—scientists disputed the promising tally of numbers provided by the WWF showing an increase in tiger numbers since 2010, as it was based on methods which, while widely accepted for many years, may not necessarily embrace the best practices available—which are more difficult but more accurate. Of course, accuracy tends to cost more.

3. Conflicting priorities.

As is the case with many iconic species which are under threat, tigers occur in regions and countries where poverty is rife, war is common, and corruption is ingrained. This presents several problems. It is both controversial and difficult to enforce conservation laws in communities where it is, quite literally, a choice between the survival of tigers, and the survival of people.

When people are living hand to mouth, preserving a species which threatens not only their lives but also their livelihood (livestock, commercial use of forest resources) becomes a logistical nightmare. Tigers are not alone in this—on my current home continent of Africa, elephants, lions, cheetahs, are just some of the species facing similar pressures and challenges.

Yet the lessons learned in recent times in Africa show that sometimes simple solutions are remarkably effective, such as the method developed by a young boy from a rural Kenyan village to deter lions from their livestock camps. You can learn more about Richard Turere’s ingenious, and oh-so-simple, idea here.

4. As with the rhino, one of the largest contributing factors in the tiger’s rapid decline is the intense demand for body parts in the Asian traditional medicine industry.

This, combined with the ever increasing rarity of such body parts, is forcing the price up, making trade in tiger parts highly lucrative.

This latter point is highlighted by the “Tiger Temple” debacle. While I was elated to see that the temple (supposedly a sanctuary for tigers while in fact it was hell on Earth) had finally been closed down and the monks involved arrested for prosecution, I was astonished that this process took so long.

It was a delicate operation to be sure—the temple was a massive tourist draw card, and after being featured on National Geographic channel, was very much in the public eye. But it also points to both corrupt influencers who had their fingers in the pie, and the slow turning cogs of bureaucracy which hamper the agile response often required in conservation emergencies. The positive side of the Tiger Temple take-down? It uncovered a whole world of shadowy trading in tiger parts, and now that the light has been shown into this world perhaps it can be dismantled. Of course, to finally save the tigers, we need education, education and more education.

The rise of conservation in Asian nations is a phenomenon of note. Many of those involved point out that most of the people using traditional medicine based on animal parts are from an older generation who won’t be around for too much longer.

In the meantime, efforts are being made to provide synthetic alternatives; laws are being strengthened, and agencies are being given the “teeth” to enforce them; and fair trade and sustainable industries are being encouraged to provide steady, safe and fair wages to allow communities to take a longer term view of conservation.

We can only hope that the tigers can hold on long enough, to benefit from the efforts being made on their behalf.

Author: Junaid Iqbal

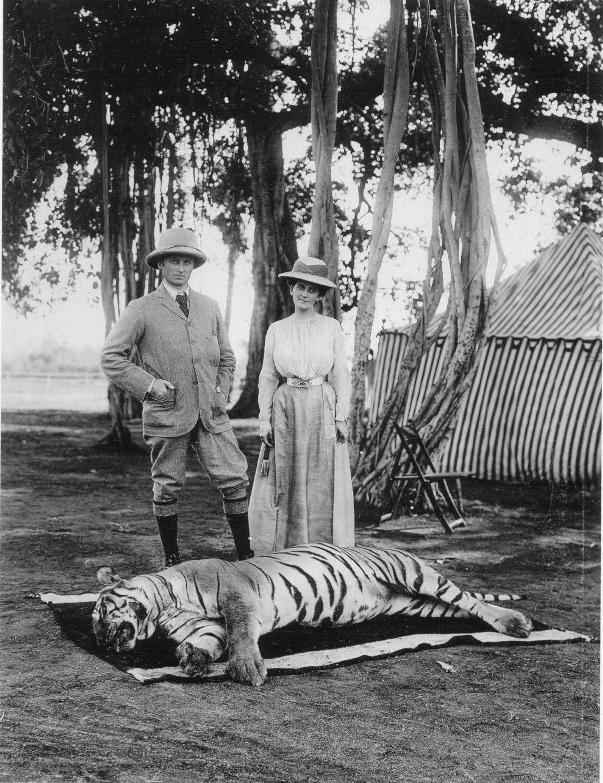

Image: Ernst Stavro Blofeld/Wikimedia Commons

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Read 0 comments and reply