Conversations with a man from occupied Balochistan.

I met my contact in the most unexpected and unsolicited way. Through Facebook.

I’ll admit it, at first I thought he was just another man reaching out to a pretty face over social media. A practice that seems all too common.

But what ensued has become a truly galvanizing conversation, connecting two people who live worlds apart. His words, thoughts and conversation have revealed nothing less than the quintessential gentleman.

We spoke of romantic literature, philosophy, religion, ethics, concepts of God, and politics. Of lost loves, dreams and funny stories. I teased him that he smoked too much and didn’t sleep enough. He shared with me his favorite novels, authors and poems. We exchanged childhood photographs. Like me, he had been a cub scout. Unlike me, he was a whiz on the flute. We shared recipes. He taught me how to make short work of a Rubik’s Cube, and explained how being the top of his class and learning English had changed his life.

He taught me how to say “thank you” in Balochi: Minnathwar. The word is forever ingrained in my being.

One night, as I blithely went about my business, I received a message that stopped me dead in my tracks:

“Do you know about Balochistan?”

The world stopped for a moment. The question felt loaded.

What did I know about Balochistan? Goodness…to be honest, I hadn’t even heard of it until we’d started chatting.

I wasn’t sure how to share this information with you, the reader, without overwhelming either of us in layers of political detail. I fear we suffer enough from information overload as it is. So, instead of making this a news piece, filled with facts and figures, I have decided to keep it simple by sharing my own experiences, as I learnt this information for myself. The identities of those involved have been withheld to avoid jeopardizing lives.

Here goes.

My friend lives in Balochistan.

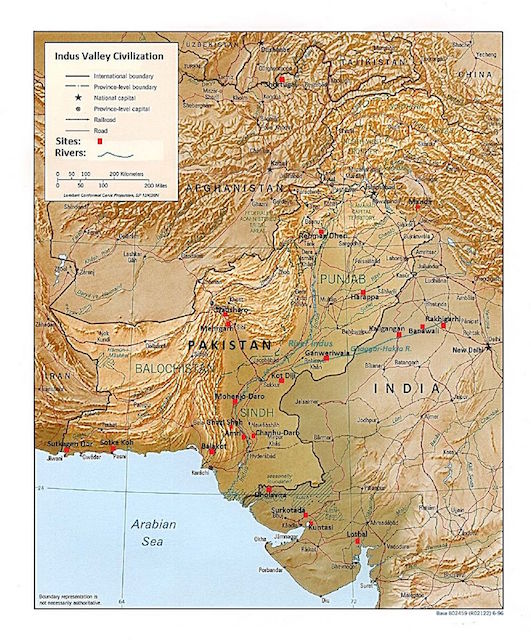

Officially, it’s one of the four major provinces of Pakistan. What I didn’t know is that the Baloch people consider this land to be independent since 1947. Their view is that their country is occupied by a violent and unjust Pakistani military.

Genocide and human rights violations have become common.

He explained what it’s like to live in a state occupied by military forces. How the people hate their own “official” language. That there are no households left in which a family member has not been murdered.

He tells me of his uncle, a kind, well-loved and community-minded man, not much older than him, who was kidnapped by the Pakistani military. He was then beaten brutally, killed, and “dumped” in the streets near where they had lived—streets that look all too similar to those from my own Namibian childhood.

My friend almost spits the word “dumped.” I don’t blame him. I can’t imagine what it must be like to have someone I live with, love and care for—someone who inspires me—kidnapped and found dead in an almost unrecognizable heap in my neighborhood.

A sacrilegious ending for any soul.

I have seen photographs of his uncle. He’s my age. Handsome. His eyes are kind. Filled with both smiles and deep sadness. His body language is gentle and down-to-earth.

This case is far from isolated. As I pour through what the internet has to offer on the topic of Balochistan, images of grey, battered corpses bombard me. I watch on YouTube as five Baloch men are marched into the forest, lined up and shot with rifles by what is reputedly the Pakistani military.

I steel myself.

We have been desensitized.

This is not a movie or a computer game. What I have just witnessed is five real young men walking meekly, with bowed heads, to their deaths. This could have been my friend.

It could have been any of us, if things were different.

I felt sick. I was struck by the sensitivity and depth displayed by my new friend. How could someone living in such a place seem so gentle, lucid and filled with goodness?

I sensed a grace that challenged my preconceived ideas and unconscious prejudices. The more he shared, the more I was struck by the humanity, intelligence and soul of each of the individuals targeted. While his town isn’t riddled by bullet holes, I understand he is searched by armed guards every day.

It hurts to hear these things. I feel frightened on his behalf. Frightened that even by talking to him I am putting him at risk.

I asked him what freedom means to him, living in such a place. This was his response:

“Such questions were asked by the great philosophers, Aristotle and Socrates, long ago.

They asked: What is freedom? What is virtue? And so on. What is good or bad?

What is good to do, what is good not to do? So your question is really interesting.

See, I am not talking about physical freedom. What else can freedom be, but the feeeeeling of freedom? [He draws out the word “feeling” for emphasis.] I will give you an example to show you what it’s like here:

Here I am, sitting in my room, and we’re discussing politics. I hear some footsteps outside my room. Coming to my door. The light goes on and off.

I feel unsafe. I feel like our discussion is being listened to. Like I’m being watched.

If we’re not free to discuss topics like God or politics—if we’re not free to speak up against our leaders, for fear of our lives—we’re not free.

Simply put, we don’t have freedom of speech. With this sort of fear, we feel unsafe in our own homes. In other places, people feel that they can express themselves because their governments honor and respect their rights and uphold their safety.

We have lost that here.

For me, freedom is all about internal freedom. The ability to say anything or go anywhere. At least free to walk in and out of your boundary, without fear for our lives. This is freedom for me. Today, we don’t have this…there is no internal freedom.”

The last bit cuts me to the quick. I had expected an answer along these lines. Due to chronic illness, I had been bed- and house-bound for many years, giving me some perspective on feeling trapped. In my case, I felt trapped in my own body. Trapped by financial constraints. And trapped by the fact that I live far away from things.

But I had had a safe space in which to develop a sense of internal freedom.

The realization rippled through me, like an icy wave. How proud I had felt at overcoming my own internal sense of entrapment. And yet, how flimsy my entrapment really was. I had taken national peace for granted.

How stupid all the things we worry and fuss over seem.

We disregard the simplest blessings without a second thought. We are so caught up in our little lives that our problems seem astronomical, at times. Meanwhile, the lives of those distanced from us, who often suffer in ways we can’t comprehend, are valued by the tone they are given on social media and in the news—if they are even mentioned.

I hope we will resist the temptation to distance ourselves from these atrocities committed on the other side of the world. The answer is not to try to shoulder all the pain, but to consciously refuse to become desensitized by Hollywood fiction, overwhelmed by sensationalized news stories or blasé at the suffering of those we consider to be “other.”

I’d like us to consider our own humanity every day, as we consider how it is stolen from others.

Perhaps recent events around the world will bring this message home in a way that shakes the very foundations of our own definitions of freedom and humanity. Despite their profoundly awful nature, stories like this are only half of the equation. They pose a question to all of us, the answer to which we can only find by searching the dark and raging alleys of our own frightened but fiercely loving hearts.

This might be a rough time we’re coming up against as a global family. I feel it. Perhaps you do too.

And yet, responding by shutting our doors or pointing fingers only desensitizes us. Those who suffer the loss of their freedom, those who live in places that are war-torn—they are not spectacles on the news. They are people, with families, loves, secrets, hopes and stories, just like you and me. They are our allies. Our teachers. Our friends.

Their worlds affect ours. Increasingly so.

For me, an internal sense of freedom is the most important thing. It’s not a matter of acquiring it, offhand.

We have to work at it. We have to talk about it. We have to develop it in our own lives.

History shows how easily it can be whisked away by things outside of our control. Could it be that by talking about it, especially with those outside our usual circles, we can instill a deeper appreciation of freedom, humanity and community? If we cannot empathize with one another, despite distance and difference, we might begin to feel utterly trapped, even in the most ideal circumstances. Isolation, ignorance and fear often go hand in hand.

By working together to supersede our circumstances, perhaps, we can begin to dismantle the suffering in our world, piece by piece.

So, to my wonderful friend from Balochistan, and to all of you:

Mani Ustaad bayag a Minnathwaar.

Thank you, for being my teacher.

I hope that we will always work together, to make things right.

~

Author: Catherine Simmons

Image: Wikipedia Public Domain; Garry Knight/Flickr

Editor: Toby Israel

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply