Q: When we feel anger, what should we do? Repress it, show it if it’s not harmful to others, or ignore it?

Lama: The first thing you can do when somebody makes you angry is to analyze the situation, especially what caused it and its effect. When you analyze the situation, start by looking at how anger projects its object—how it concretizes and exaggerates the object. When you analyze the evolution of your anger in detail, you can’t find that concrete object anywhere. That’s one way of eliminating anger.

Another thing you can consider is if it’s worth hanging onto your anger. The moment you conclude that it’s not worthwhile—that anger destroys yourself and others—you can change your mind and let it go. The inner conversation that breeds resentment and perpetuates anger—“He did this, she did that, he did this, she did that”—simply agitates your mind and is completely not worthwhile.

By analyzing the evolution of your anger and seeing what a ridiculous mind it is, you can weaken and eliminate it even intellectually. Anger can arise over really small and silly situations. For instance, families can argue over where to put a bowl of flowers. I put it here, my wife wants it there, and from that small beginning a huge fight can erupt. We don’t need big reasons. Simply not accepting change can cause anger to arise. So we need to analyze reality. Things change; that’s their nature. Accept and let go. Put it here, put it there—what difference does it make? Sometimes we think something’s so important and desperately want it to remain as it is. That’s wrong and can often lead to anger.

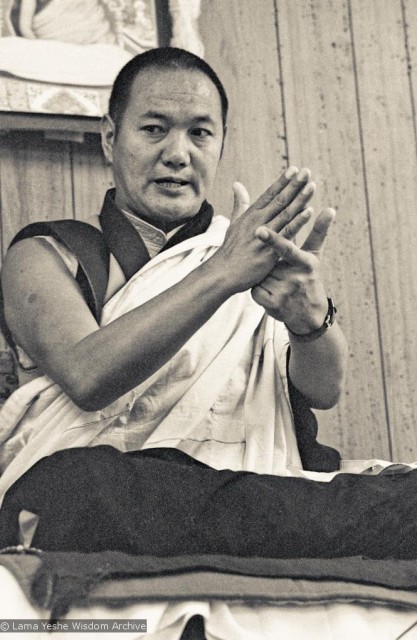

Lama Yeshe teaches at University of California’s Oakes College, Santa Cruz in 1978.

Buddhism always stresses impermanence; change is natural. It has nothing to do with concepts. Flowers gradually evolve from seeds planted in the ground; babies grow into children, then adults, age then die. This is the natural way things go. Wives change; husbands change; girlfriends change; boyfriends change—it’s all natural.

Therefore, it’s very important to accept change, because it’s respecting nature. When you’re angry, you don’t respect others. Others want to change something, but you don’t—that means you’re disrespecting others’ will and the natural process of change.

And the main thing is that Buddhism considers anger to be the worst of all delusions. The moment you get angry, you become negative, and others appear negative to you. Buddhism does make an exception for desire; even though it’s usually negative, there’s a way to make it positive and bring positive results.

So, since anger is our worst enemy, we have to make every effort to abandon it; trying to do so is good enough. We should try thinking, “Anger destroys my peace and pleasure and that of others. Controlling it is of utmost importance in my life.”

When we get angry, how do we see the object of our anger? In the morning, that person may have looked extremely attractive, but in the afternoon, when we’re angry, he looks horrible, ugly. Obviously it’s not possible that he changed so radically from his side; it’s simply our projection exaggerating what we perceive as his bad qualities. Therefore, we shouldn’t believe that he’s really bad, but recognize our view and reaction as coming from our own mind.

Q: Lama Yeshe, what about killing to preserve the lives of other beings? Is it ever acceptable to kill in order to save others?

Lama: That’s a very dangerous question. I want you to listen very carefully to my reply so that you don’t misunderstand what I say. So, let’s say I have a nuclear weapon and am planning to blow up New York City and kill millions of people and you know clean clear that this is my intention. I think it would be all right if, out of great love, great compassion and great wisdom, you were to kill me. Why? Because you’d be doing it for the sake of all those people whose lives I’d have destroyed.

This question is similar to what several of my medical doctor students have asked me. Some of them have been disturbed because they have had to kill rats and monkeys in medical experiments; they know Buddhists aren’t supposed to kill any living being.

I have to answer, don’t I? I can’t ignore them. So I say, “Well, as long as your research will benefit humankind and even animals as well, I guess experimenting on and killing one monkey might be okay.”

The point is, if you have great compassion and a clear understanding of what benefits the majority, perhaps there can be exceptions. But still, I have some doubt. If our understanding is limited we can easily make mistakes. Therefore, exceptions to the Buddha’s injunction not to kill would be extremely rare.

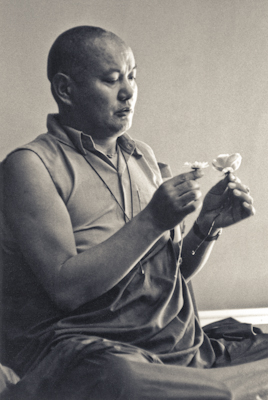

Lama Yeshe teaching at Yucca Valley, 1977.

Q: How should we deal with people who consider us as their enemies or people who don’t trust us?

Lama: With compassion. According to the way I was educated, people who hate you are objects of love and compassion. Why? Because they are not enemies forever; tomorrow they can become friends. Therefore, there’s no such thing as a self-existent, concrete enemy.

We should know from our own experience that things always change. Today somebody can be a dear friend, tomorrow an enemy. Who knows? It’s all so relative, but so common—look at how many marriages break up, with people who were once loving partners regarding each other as mortal enemies. Before they couldn’t bear to be apart; now they can’t stand the sight of each other.

Therefore, I think it’s important to deeply imprint your mind with the knowledge that there’s no external enemy, so that if one appears to manifest today you don’t get caught up in hatred and just let go, thinking, “By hating me, he’s hurting himself; he’s suffering. What is it in me that upsets him so much?” Do you see Buddhism’s reverse thinking? We think there’s some kind of destructive vibration in me that makes him hate me. I’m actually responsible for others not liking me. This is opposite to what we normally think; we think the hurt inflicted on us by our enemy is his fault.

Lord Buddha’s psychology is that we have some kind of negative magnetic energy within us that stimulates anger to manifest in another person, whom we then label “enemy.” Controlling that energy within us is the best way to eliminate enemies. From the Buddhist point of view, seeing others as enemies and wanting to destroy them is completely wrong.

The great bodhisattva Shantideva said that if the ground is covered in thorns it’s easier to avoid getting stuck by putting on shoes than by covering the ground with leather. Wearing shoes has the same effect as covering the ground with leather. Similarly, if we control our anger with patience, no external enemy can be found. Our main enemy is within; that’s the one we have to conquer. If you try to destroy external enemies, how far can you get? Maybe you can kill one or two people, but more enemies will arise. You can’t get rid of enemies that way. But if you get rid of the mind that sees enemies, no further enemies will ever be seen.

~

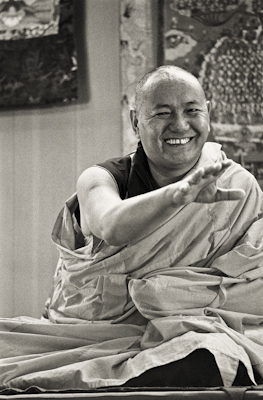

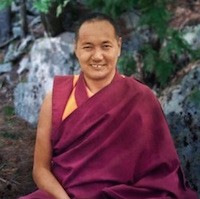

Lama Yeshe answered these questions after a talk on “Anxiety in the Nuclear Age,” given at the University of California, Santa Cruz, 23 July 1983. Edited from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive by Nicholas Ribush.

Image Credits: Carol Royce-Wilder; Jon Landaw (all images via the author)

Ele-editor: Toby Israel

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply