I was recently chatting at a party with a friend and something in our conversation prompted her to ask if I believed in God.

I was taken off guard and stuttered something vague and non-committal in reply. My inability to answer with clarity concerned me, and when I thought about it further, I realised I didn’t actually understand her question.

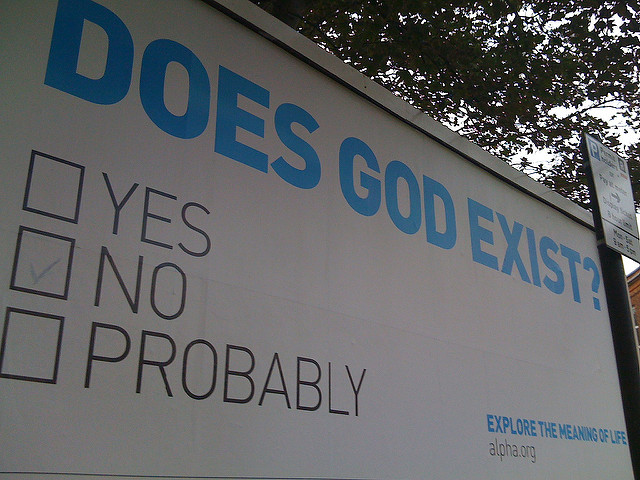

What do people mean when they say they “believe in God?”

Do I know that God exists? i.e. “do I have an ‘inner sense’ of his existence?” or

Do I feel that God exists? meaning “do I feel his presence in my daily life?” or, maybe,

Do I think that God exists? That is, “do I consider the probability to be high?”

To these three questions, I would honestly answer “no,” “I’m not sure” and “I don’t know.”

So why do I then (mostly) observe the Jewish Sabbath, go to the synagogue (most) days, eat (mostly) kosher food and observe other Jewish laws and practises?

Because, for me, whether or not I believe in God is not important. What is important is whether or not God actually exists.

I’m not smart enough to know or “spiritual” enough to feel if God is definitely out there, but I’m open to the possibility that he might be and my life is transformed by entertaining that possibility.

If God exists, life is no longer random, but directed. We all have a specific purpose to fulfil in this world, which gives our lives meaning. Good deeds performed in this world, ultimately, will be rewarded and bad deeds will be punished. There’s an absolute moral system through which universal “right” and “wrong” are determined. In essence, life is more meaningful and just.

In the Western world today even though many people are unsure about God’s existence, they are still open to the possibility of it. However, in practise, they live their lives as though God does not exist and therefore completely miss out on the important and worthwhile aspects of religion.

The Bible and many other religious works obviously claim that God does exist. But our secular, science-based society asserts that there’s no tangible evidence for this. While, for some, there is obvious proof of God’s existence all around us in nature and through human emotions such as love and joy, even they admit that God has decided to hide from the world.

Blaise Pascal, the 17th Century French physicist, mathematician and philosopher, argued that our best course of action is to believe in God, regardless of the lack of evidence, because that option gives the biggest potential gains. This is Pascal’s Wager where he compared the finite and measurable “costs” of living a religious life in this world (for example, of me not eating whatever I want) with the possibility of, if God exists, receiving infinite “rewards” in the next world. Mathematically, even if the probability of God’s existence is small, the potential of enjoying such huge rewards in the next world—forever—means that it would still be rational to live religiously during our time in this one.

So Pascal argued that we should pay our spiritual insurance premiums now, just in case we need to claim them later. But that’s not completely satisfying for me as I am also concerned with happiness and meaning in this world right now.

A number of studies have proposed that leading a more religious life can bring a host of health benefits, particularly in stressful situations. For example, the World Happiness Report, stated that “greater religiosity is mildly associated with fewer depressive symptoms and 75 percent of studies find at least some positive effect of religion on well-being. This effect is particularly prevalent in high-loss situations, such as bereavement, and weaker in low-loss situations, such as job loss or marital problems. Thus religion can reduce the well-being consequences of stressful events, via its stress-buffering role.”

This makes complete sense to me, as it would be very stressful to believe that everything that happens in my life is either a result of my own actions or, worse, of random events. Much more calming is the possibility that a loving God exists who can see life’s big picture, is in control and has my best interests at heart.

But can we really choose what to believe? Do we have the control to believe or disbelieve anything at will?

Well, we make choices in our lives all the time where we have incomplete information or where we just do not have the time, energy or ability to collect it. This is true of decisions ranging from what investments to make, who to marry and whether or not to undergo a medical procedure. We assess the potential gains and losses to the best of our knowledge, make our choices and live with the risks and costs.

So why should decisions about the religious aspects of life be any different? Maybe because they are unfashionable or maybe because the concepts are too intangible and the associated consequences too enormous for many people to engage with. We can choose not necessarily to believe in God (whatever that means) but to be open to the possibility of his existence and what that possibility would mean for our daily lives.

How can we do that? To start with, just simple things like taking time out (i.e. turning off the phone) to pause and ponder or meditate on the possibility that the universe has a benevolent creator, and to be grateful for what we have been given. Also considering how we can be our best selves and fulfil our potential—for others, for ourselves and, potentially (in case he made us), for God. And treating everyone well—including strangers—as if we are all connected and from the same source.

Do I think God exists? Possibly. Do I hope God exists? Yes, absolutely.

~

Author: Steve Lewis

Image: Ben Godfrey/Flickr

Editor: Katarina Tavčar

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply