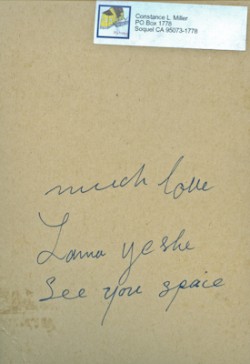

Lama Yeshe meditating with his dog Dolma.

Each human being has a mind, and that mind has three divisions: gross, subtle and most subtle. Similarly, we have a body and that too has three divisions: gross, subtle and most subtle.

The gross consciousness comprises the five sensory consciousnesses that we use every day. The subtle consciousness can be things like intuitive ego and intuitive superstition. They’re subtle in the sense that we can’t see or understand them clearly.

The gross mind is so busy that it obscures the subtle. When the gross mind is no longer flashing, or functioning, the subtle mind has a chance to arise. And that’s one of the functions of Tibetan Buddhist tantra: to eliminate the gross concepts and make space to allow the subtle mind to function. That’s the business of tantra.

Also, the gross mind has no strength, no power. Even though it understands something, it’s relatively weak. The subtle mind has much more power to penetrate and comprehend.

What meditation does is cut the gross, busy mind and allow the subtle consciousness to function. In that way meditation performs a similar function to that of death. Of course, to do the kind of meditation that leads us through the death process we need strong single-pointed concentration.

As you know, Buddhism explains emptiness [Skt: shunyata], the nature of universal reality. We experience emptiness when elimination of the gross, superficial, conventional mind allows it to manifest. Even people who have never heard of emptiness and have no idea of what it is to experience a great emptiness in their mind during the death process when all their busy minds dissolve.

The moment your gross, crowded concepts stop you feel some space, an emptiness. There’s nothing you actually empty but because your concepts are so crowded, because your mind is so full, when all that content disappears you have an experience of emptiness.

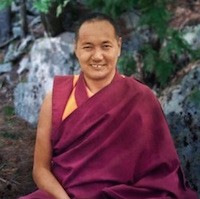

Lama Yeshe teaching, Fourth Meditation Course, Kopan Monastery, Nepal, 1973.

Sometimes when Buddhist philosophers describe shunyata, “blah, blah, blah, blah, blah,” it sounds so complicated. And it’s true; Buddhist philosophy is very sophisticated. Ordinary people don’t understand. “How can I possibly understand shunyata? Nagarjuna says, ‘blah, blah, blah’; Chandrakirti says, ‘blah, blah, blah.’” But when we really bring it back down to earth, all we’re saying is, when you cut your crowded superstitions, the experience comes; when you eliminate all your busy concepts, the experience of shunyata arises, as it does in the death process.

At the moment we’re normally far from reality—from the reality of ourselves; from the reality of all that exists—because we’re enveloped by a heavy blanket of superstition.

One blanket of superstition; two blankets of superstition; three blankets of superstition…this blanket, that blanket, another blanket…. All these gross blankets, gross minds, completely built up, like Mt. Meru, like Mt. Everest—so heavy that you can’t shake them off.

Now, I don’t know what methods you normally use, but our business this weekend is to look at the Buddhist method of slowly, slowly removing these blankets one by one: meditation. And in order to do that, we have to understand the characteristic nature of our own mind.

First of all, the mind is not a material substance; it has no shape or color. It’s a kind of formless, colorless energy: the energy of thought or consciousness. Therefore its nature is clean clear and it takes the reflection of phenomena inside. Even thoughts you consider to be heavy and negative still have their own essence, their own clarity, in order to perceive reality or reflect projections.

Also, consciousness, or mind, is like space. The essence of space is its own nature, unmixed with pollution or clouds. The nature of clouds, the nature of pollution and the nature of space are different. Even though pollution pervades space.

The reason why I’m mentioning the negative mind is that we humans have a normal tendency to preconceptions such as, “I’m a bad person, my mind is bad, I’m too negative.” We’re always criticizing ourselves in a dualistic way. Buddhism says that that’s wrong. The characteristic nature of space is not pollution; the nature of pollution is not space. Similarly, the nature of the consciousness is not negative. In fact, the Buddha himself said that buddha, or tathagata, nature lies within each of us and the nature of that is pure, clean and clear.

The reason why I’m mentioning the negative mind is that we humans have a normal tendency to preconceptions such as, “I’m a bad person, my mind is bad, I’m too negative.” We’re always criticizing ourselves in a dualistic way. Buddhism says that that’s wrong. The characteristic nature of space is not pollution; the nature of pollution is not space. Similarly, the nature of the consciousness is not negative. In fact, the Buddha himself said that buddha, or tathagata, nature lies within each of us and the nature of that is pure, clean and clear.

Also, Maitreya explained that if you put a diamond in kaka, its nature remains different from that of kaka and the nature of the kaka remains different from that of the diamond.

It’s important to know this. A clean clear mind exists within us; the fundamental nature of our consciousness is pure. But while our mind has its own essence of clarity, it’s covered by a contaminating heavy blanket of concepts. Nevertheless, its nature is still clean clear; our consciousness is clean clear. Therefore we have to recognize, “My nature, the essence of my consciousness, is not totally negative. The pure, clean clear nature of my mind exists within me right now.”

~

Lama Yeshe gave this teaching in Geneva, Switzerland, in September 1983, his last teaching in the West. Edited by Nicholas Ribush. Read more teachings by Lama Yeshe on the nature of mind.

Author: Lama Yeshe

Image Credits: First Image : Fred von Allmen, Second Image : Lynda Millspaugh, Third Image: Connie Miller(all images via author), Wikipedia

Editor: Travis May

Read 0 comments and reply