The modern world often relates the icon of La Calavera Catrina to the traditional Mexican celebration of The Day of the Dead, or El Día de Muertos.

Once in a while, I remember the story my dad used to tell me when we spoke about dying.

“When you were a baby, hija, you died for a couple of seconds.”

Or at least that is how it felt to him. It was a story worth remembering, not only because I had almost died, but also because it was when, he said, I spoke my first word.

As if the intensity of knowing that your baby, barely one year old, was affected by pneumonia, treated with Penicillin by her doctors—resulting in a bad allergic reaction and almost dying—wasn’t enough trauma, he went on to tell me the climax of the story: he was holding me in his arms when my eyes suddenly rolled up, showing only white as if I was dead, and just at that same moment, uttered “Papa” to him for the first time.

In this moment that he has remembered forever, he felt I had been paid a visit by La Catrina—the elegant Mexican Grim Reaper.

Today I learned that the origin of La Catrina dates from the 19th and 20th centuries. The skull was used as a political criticism of the conditions of inequality lived during those times. As told by historians today, writing contests promoted during the era encouraged people to compete in writing what we know as “calaveras,” or satirical texts in verse, which were used to critique living situation of the majority of the country’s occupants compared to its more privileged classes.

Through often funny rhymes, writers would exhibit the suffering that people endured throughout the great social differences created by the El Porfiriato era.

Among several competitors, there was a Mexican political printmaker and engraver whose work has influenced many Latin American artists and cartoonists because of its satirical acuteness and social engagement. He used skulls, calaveras, and skeletons to make political and cultural critiques.

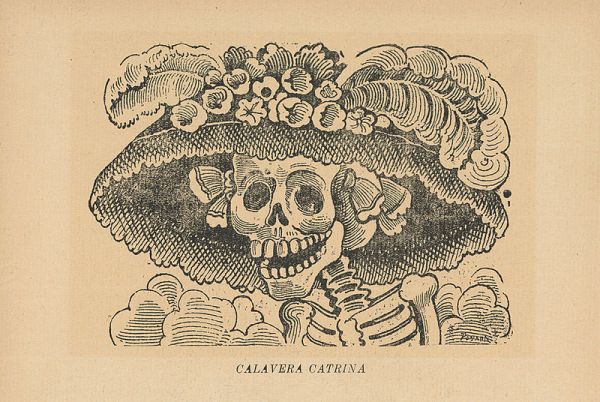

José Guadalupe Posada created a nude skull, wearing only a hat and named her “La Calavera Garbancera.” This represented criticism toward the native people who pretended to be better than others by acquiring European customs. For Posada, this meant they rejected their roots and their own culture. That is why the “calavera” was nude, as an allegory to those who possessed nothing material, but wearing a hat with feathers, typical of the era and used only by the privileged classes.

Years later, the muralist Diego Rivera turned La Calavera Garbancera into La Catrina. This name refers to the fashion associated with the Aristocrats, who like to describe their wardrobe as elegant. And that is how they came to be called catrines or catrinas.

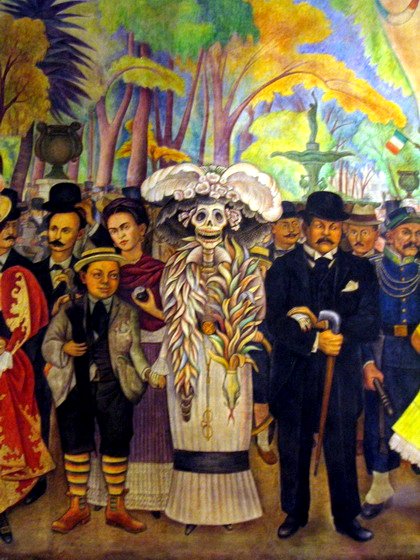

Now, La Catrina appears elegantly dressed in the mural Sueño de una tarde dominical en la alameda where the calavera appears with its creator, José Guadalupe Posada, along with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera.

In this new millennium, when La Catrina appears around the world on November 1st and 2nd, everyone knows it is The Day of the Dead. Beautiful and worth remembering is Posada’s message:

“Death is democratic, since at the end of it all, blonde, brunette, rich or poor, everyone ends being a calavera.”

In the spirit of the times, November being election month and all, what is your “calavera” for the times you are living? Write your verses in the comment area. I would love to read how you see your world, through the spirit of death.

~

Author: Yesica Pineda

Images: Wikimedia Commons; Wikimedia Commons

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Read 0 comments and reply