There were two topics in the news recently that captured my attention.

Both dealt with journalistic blunders. One was the surprising turn of events during the U.S. presidential elections. The other—with less fanfare—was the conclusion of the Rolling Stone’s defamation case following the retracted article “Rape on Campus,” published in 2014.

Both cases illuminate the current state of flux in journalism and the major changes in the way we consume and serve the news today.

I have been observing this relationship, albeit on a much smaller scale, play out from the microcosm of elephant journal, where for the past two and a half months I have been curating the Ecofashion Facebook page.

The page reaches an average of a million readers per week and I was giddy with the possibility to contribute to the dialogue on mindful fashion. I was researching pertinent information on relevant subjects, digging deeper to create my own content and posting the articles that I found meaningful.

Within the first week my zeal was dampened when I started to analyze what my fellow ecofashion-lovers were responding to. Any time I post an article on the subject of mindful fashion, which describes the impact our consumer addiction has on our planet, those articles get minimal to average attention.

The articles that go through the roof or “blow up the page,” to use my newly-acquired jargon, are on astrology, relationships and…sex. Granted, all the articles on elephant journal are focused on the mindful life and always try to be of benefit to its readers. The point is: articles that are more “entertaining” are read more eagerly than the ones that talk serious facts.

So when my post reach is on the wane and I need to engage with my readers and get them to pay attention, guess which articles I post more of? Hint: it is not about our planet going to hell.

And this, in a nutshell, is the drama that I have watched play out on the global screens last week—the news we get are the news we want to read.

Mainstream media has been struggling with the onslaught of digitally available information, under the pressure of falling readership and declining revenues. To compete for readers’ attention, they either resort to sensationalism, as in the case of the Rolling Stone’s article, or serve up what the readers want to read about, as in the case of making voter predictions.

The problem is that this all too often leads to disregard of basic principles of good journalism and, as a result, discredits the reputation of mainstream media even further.

In the Rolling Stone’s defamation case, it was shown that unscrupulous journalism has destroyed reputations of many on both sides of the suit and discredited a subject of national importance.

Driven to break the sensational story that would get attention and sell the magazine, the activist award winning journalist with a long career let her desire to prove what she believed was happening guide her decision-making, never bothering to take a cold objective look at the facts. The 10-page report was extremely graphic in its description of the rape, exposing the inability even by such seasoned and serious publication to resist the temptation to give the reader the attention-grabbing “juicy” details.

In the case of now infamous failure of mainstream media to predict the outcome of the election, journalists’ disregard for the normal rules of journalistic objectivity may have affected the course of history.

Instead of being on the road capturing issues close to voters, the journalists got into the business of predicting voter opinions, instead of listening to them—and wrote off the unconventional and inexperienced candidate based on their own opinions.

The arrogance of an elite and entrenched hierarchy led to predictions that were not properly scrutinized. Some of the modeling used to predict results of the election was simply out of step with reality. And yet, the data-driven journalism will not cease to exist, because “there’s a huge demand among readers for this stuff.”

“This stuff” that is referred to is all sorts of polls, which readers love and put a lot of faith in. However, besides the statistical issues that make polling inaccurate, you cannot predict human behavior, and voter behavior is notoriously unpredictable. People can change their minds, decide to not share their opinions or simply lie. Trump, as a candidate, cut such a scandalous figure, that a lot of voters who planned to vote for him did not speak about it.

In the end, the readers wanted certainty, reassurance, and a look into the future. The data-driven journalism seemed to provide the palatable future outcome.

We are scared about the future and worried about our ability to navigate it. So we started using the news to escape, which defeats the whole purpose of listening to the news in the first place: to be informed of the facts, no matter how unpleasant they are, so that we can then react accordingly.

My point is that we, the readers, are also complicit in the problems with how the news is served up today. We, the news consumers, set the tone by voting with our attention, our selection and our clicks.

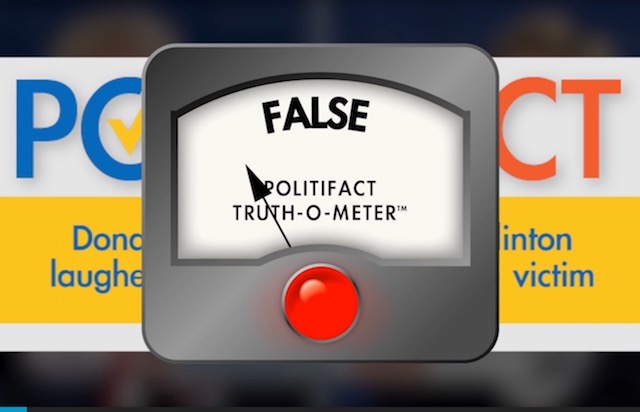

In the climate of mistrust in the authority and professionalism of a news media, all kinds of rumors and conspiracy theories flood in and go viral, as the influx of fake news demonstrated. Reacting to false information or taking for truth that which is not leads to catastrophic mistakes.

~

~

~

Author: Galina Singer

Image: Video Still

Editor: Travis May

Read 3 comments and reply