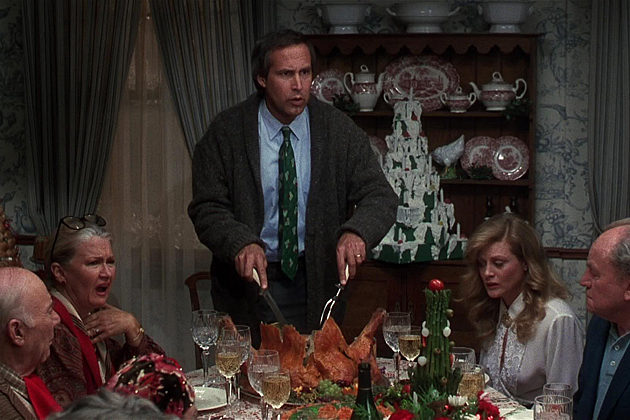

As we approach the Christmas holiday, many of us will be heading home (or hosting family) to eat an animal for dinner, drink egg nog and alcohol, and hang out with the family members we pretty much intentionally don’t see the rest of the year. What could possibly go wrong?

I’m fortunate in that none of my family members are awful, and all are fairly easy to get along with, even fun. However, that doesn’t mean that I don’t sometimes get triggered. It seems as though in these modern times, a lot of us are well-defended and operate via our well-established defense mechanisms and storylines that impact how we relate to others, especially family.

Underlying this is an “I versus you” mentality, as opposed to a “we/us” perspective. Couple that with the modern political and global state of affairs up for discussion at the dinner table—how can we not get triggered? A trigger is a reaction that is more instinctive and immediate, lacking our typical skill or thought, that has ties to our conditioning of the past.

For me, this is most likely to happen when I interpret a comment as being condescending. Oh, how that bugs me. Whether it’s a family member during the holidays, or someone in my day to day life, feeling as though someone is looking down on you, or belittling you in some way, is so annoying!

Of course, this is tied to me feeling small and insecure when I was young, and now it’s a real insult, and my reactions aren’t pretty, I’m sure. Even if the intentions beneath our mother-in-law’s commentary are benign, it might still be interpreted as condescending. Perhaps it’s because we are hyper-sensitive to these comments, based on past interactions.

At the point our conditioning takes over, our amygdala amps up (which is the little almond-shaped piece of our brain that detects danger and tells our fight or flight reactions to kick in). Our amygdala comes in handy at times, however, it’s not the best at determining when danger is real or not. It’s like the fire alarm in your apartment. If it detects smoke, it goes off. However, that smoke might be from burnt toast and not a real fire.

Can you anticipate a situation or conversation that might arise these holidays that’s really just burnt toast? And can you envision an appropriate response?

We can use these three mindful approaches, with roots in Buddhist psychology, to look at how we might approach challenging familial interactions.

1) Having a fixed view, or “knowing” what’s right often gets us into trouble by limiting our response flexibility. Why are we so attached to being right? Why do we always insist on knowing? This is our habit. When we “know” and the person we’re engaged with also “knows,” suddenly both parties are limited in how they can respond. More often than not, the result of everyone knowing is digging in our heels and reinforcing the “you versus me,” or this sense of separateness that only serves to disconnect.

We’ve all had the experience of taking a stand and defending it, and how rigid and tense that feels. Compare that to when it feels okay to be wrong, and the lightness one feels when being certain isn’t necessary, i.e., taking a playful approach. Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind is an infamous literary piece exploring the benefits and wonder of intentionally seeing things with fresh eyes. Entering into a room or a conversation with a “not knowing” outlook can lend itself to a lightness of energy that influences the dynamic. I think to be wise is to realize you pretty much don’t have anything figured out.

2) Bearing witness is just what it sounds like: witnessing whatever is unfolding before us. Instead of getting lost in our storylines of judgement, fantasy, resentment, and so on. We practice allowing the feeling to exist, without needing it to be other than it is, because we understand the impermanence of it. We are learning that this is our fixed view taking shape. We practice not making our problems such a big deal. It’s taking on the beginner’s mind, not knowing what’s good or what’s bad. This is really taking the study of our mind’s conditioning to another level. We practice noticing the tendency to judge and have expectations, being present, and not adding a story.

Bill Ball, of the Durango (Colorado) Dharma Center, recently quoted Bernie Glassman’s experience after his loving wife passed away unexpectedly. Someone asked Bernie if it hurt, and Bernie replied, “I’m raw.” “Do you feel sad?” they asked. Bernie’s reply was:

“I shake my head. Raw doesn’t feel good or bad. Raw is the smell of lilacs by the back door, not six feet away from her relics on the mantel. Raw is listening to Mahler’s Fourth Symphony or the songs of Sweet Honey in the Rock. Raw is reading the hundreds of letters that come in, watching television alone at night. Raw is letting whatever happens happen, what arises, arise. Feelings, too: grief, pain, loss, a desire to disappear, even the desire to die. One feeling follows another, one sensation after the next. I just listen deeply, bear witness.”

An indication that you’re acting from old stories is when “I, me, and mine” are ever present. This is different from bearing witness, which is something like, “right now, it’s like this.”

3) Lastly, we can take an action that is wise, compassionate, and skillful. We can choose how to respond in a difficult moment, in a challenging situation. Choosing a thoughtful response that has its roots in not knowing and bearing witness looks much different from an instinctive reaction based on our old stories. This is taking care of how we relate to our self and others. This is acting from a full heart, choosing the response with roots in compassion for yourself and the one next to you, knowing that causing the least amount of harm is the right choice.

All of this takes practice, and courage. It takes courage to be with anxiety and to be with not knowing. It takes courage to bear witness to difficult feelings, without acting on them. It’s not easy to acknowledge that we mostly operate out of past conditioning, clinging to certain outcomes, having all sorts of expectations that don’t serve anyone.

If we can practice being courageous with the present moment, witnessing our frustration and joy, our pleasure and pain, our moments can take on a sense of richness and vitality. We are really with our family at Christmas, without needing them to be anyone other than who they really are.

Isn’t this the holiday spirit?

~

~

~

Author: Robert Oleskevich

Photo: National Lampoon’s Christmas still

Editor: Travis May

Read 0 comments and reply